For those of us who are as intimate with the inner workings of the stock market as we are with the circuitry of the Large Hadron Collider, the brouhaha over GameStop has been illuminating. While the story may seem esoteric, it is highly revealing of the way economic and political power operates today, laying bare both the irrationality of the market and the reach of corporate privilege.

For those who don’t know, GameStop is a US video game retailer that has lost much of its market share to online trade and whose stock plummeted from $56 (£40) a share in 2013 to about $5 in 2019. It is set to close 450 shops this year. Some big hedge funds decided that they would cash in on GameStop’s misery by shorting its shares. A short is a bet that an asset, such as a share, will decline in price. It’s a manoeuvre that can generate huge profits. But if the asset price doesn’t fall, investors can also lose a lot of money.

And that’s what happened with GameStop. A bunch of Reddit geeks on the online forum r/wallstreetbets, an investment discussion group that boasts more than 6 million users, decided to buy GameStop shares en masse. Perhaps they saw it as an investment, perhaps they were bored, perhaps they wanted to inflict pain on Wall Street. Whatever the reason, the consequence was to push GameStop’s share price up. And up. Once it became a global story, others piled in too, boosting the share price from about $40 to almost $400 in a matter of days. As a result, big investors lost big, one hedge fund, Melvin Capital Management, even being forced to seek a rescue package. The story, however, is not just about traders getting their comeuppance, but also about the absurdity of the stock market.

One might naively imagine that it exists to allow people to invest in companies. But share trading often has little to do with productive investment. According to the writer Doug Henwood, IPOs – initial public offerings through which people can buy shares in private companies – have, over the past 20 years, raised a total of $657bn (£479bn). Over that same period, the companies in S&P’s 500 stock index have spent $8.3tn (£6trn) buying their own stock to boost its price.

A stock buyback – a company purchasing its own shares to reduce the number openly available and so push the price up – is a form of market manipulation that was illegal in the US until Ronald Reagan decided that to ban it was to restrict market freedom. As a result, many corporations, instead of building factories, now plough money into their own shares.

It has helped raise the stock market to record levels and provided shareholders with a huge largesse. But few others have benefited. The pharmaceutical company Merck insists that it must charge exorbitant amounts for its medicines to help fund new research. In 2018, the company spent $10bn on research and development – and $14bn on share repurchases and dividends. One report suggests that had Walmart diverted half the money it has spent on stock buybacks into wages, one million of its lowest-paid employees, many of whom live below the poverty line, could have had a 50% pay increase.

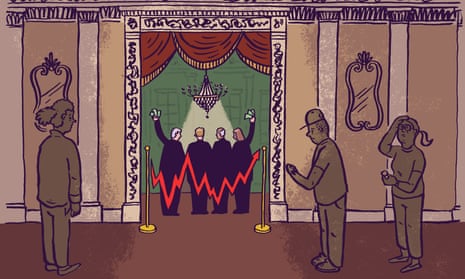

As speculation rather than productive investment has become the fuel of the stock market, so big investors have come to spend more time playing games such as shorting. Last week, though, having been outgamed by a bunch of nerds, the titans of Wall Street did what all entitled people do. They whined. How dare people manipulate the market! Only those with Manhattan penthouses who attend dinner parties with presidents and Federal Reserve governors should be able do that, not people with online handles such as DeepFuckingValue. As Severus Snape exclaims in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince: “You dare use my own spells against me, Potter? It was I who invented them.”

Having the right connections means that when you whine, others listen. Regulators in Washington are now keeping an eye on possible market manipulation by social media groups. The digital investment app Robinhood, which has helped open up the stock market to a wider public, last week restricted trades in GameStop, allowing investors to sell but not to buy, a sure way of pushing share prices down. The company insists that this was for technical reasons rather than from a desire to protect hedge funds. Small investors have, however, taken out a class action against Robinhood for “knowingly manipulating the market”.

Discord, an online platform, banned wallstreetbets from its servers for spreading “hate speech, glorifying violence and spreading misinformation”. By all accounts, group members indulged in racism and homophobia. Its founder, who was expelled earlier this year, claims that some moderators “were straight-up white supremacists”. It’s quite a coincidence, though, that the group should be taken down for “hate speech” on the day that big investors lost so much money. At the same time, the relationship between such groups and regressive politics shows how much Wall Street has become associated with liberals and how much of the anger against big corporations has been hoovered up by the populist right.

Discord’s action demonstrates again the power of tech companies to shut down groups or discussions that those with power and influence find troublesome. It demonstrates, too, how campaigns against “hate speech” or “misinformation” can become means of throttling much wider forms of challenges to authority.

There might be something cathartic in watching the wolves of Wall Street themselves beeing savaged, but we should not romanticise the Reddit geeks. This was not an “uprising” or “the French Revolution of finance”, as Donald Trump’s former communications director Anthony Scaramucci absurdly described it, but a scheme to play professional investors at their own game.

Many of the players are undoubtedly unsavoury figures with regressive politics. Their actions do nothing to challenge the inanities of the stock market or to diminish the miseries the market imposes on so many people’s lives. On the contrary, what the GameStop affair reveals are the frailties of the contemporary challenge to power.