Empathy

Let's Ponder Sonder

Do we need a word for this? Yes!

Posted January 10, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

I hate to start on a sad note, but my favorite coffee shop closed down recently. The good news, of course, is that we live in a golden age of coffee shops, where it’s often hard to fall over without falling into a coffee shop.

I’ve visited lots of local coffee places in my search for a new favorite, looking for the right combination of scones, caffeine, good tunes, almond milk, outlets, more scones, and a catchy wifi password. Yesterday, I stopped into “Sonder Coffee and Tea.” I’ll leave it to Yelp to provide reviews, but the best part for me was the new word I learned.

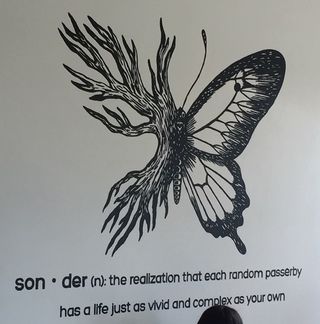

I figured “Sonder” was the name of the owner or an exotic tea, but on the wall of the shop was what appeared to be a dictionary entry: “son-der (n): the realization that each random passerby has a life just as vivid and complex as your own.”

I had never heard that word before! That itself is not a surprise because my vocabulary is not the greatest—I’m reminded of that every time I read Updike, or Morrison, or anybody else. But sonder seemed pretty short, which is the kind of word I usually know. So I did some research.

What I found was that sonder is a new word, not (yet) listed in traditional dictionaries. Wiktionary says this: “Coined in 2012 by John Koenig, whose project, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, aims to come up with new words for emotions that currently lack words. Inspired by German sonder- (‘special’) and French sonder (‘to probe’).”

He mentions that people’s lives are “populated with their own ambitions, friends, routines, worries and inherited craziness—an epic story” in which we, the observers, “might appear only once, as an extra sipping coffee in the background…” You can read Keonig’s extended and eloquent definition in his wonderful collection of neologisms. (He even includes a beautiful video.)

When I read this, it reminded me of people passing the seemingly interminable times when they’re in airports, bus stations, and faculty meetings, making up stories about the people around them: “That person is a spy, born in a small town in central Pennsylvania to a disgruntled opera singer and a mechanical engineer. They’re on their way to Tampa to meet their contact, ‘Heath,’ to plot...” I always had the suspicion that the stories I devised were less interesting than the peoples’ actual stories. Sonder.

Koenig writes as if sonder is a sad emotion, ostensibly because we can never know everything about everyone and that we may matter so little to others. But I see it as a very positive emotion as well. In psychotherapy, sonder can help therapists develop and express empathy for their clients—and it can help clients put their own experiences into perspective.

Sonder may help me as a teacher. For example: Appreciating students’ lives as rich, complex, and important may set the stage for greater understanding, relating, and learning.

Sonder becomes even more important as I teach students who are different from me. Most of my students are different on at least some of almost every conceivable dimension—age (this difference grows every year!), gender, ambitions, test performance, grades, place of birth, religion, height, writing ability, intellectual prowess, political beliefs, academic experiences, hair color, sexual preference, family background, etc.

I’m sure you can add other characteristics to the list. For now, the list is good enough to help us invoke some basic ethical principles. Let’s start with justice, or fairness. When I give grades, some of the characteristics on the list are (and should be) relevant and some are not. Test performance is a good dimension on which to grade—hair color is not. To grade on hair color is unjust. If sonder helps me appreciate where students are coming from, I may be more successful in helping them on the path to where they want to wind up. If I’m more effective at helping students learn and grow, I’m actualizing beneficence. To the extent that I can appreciate their unique perspectives and choices, I am also respecting their autonomy.

Sonder relates to other psychological concepts. For example: My graduate advisor, C. R. Snyder, did research on people’s need to feel unique. We naturally like to feel unique, and it may not be hard to see how we’re special. All I had to do was take my mother’s word for it. At the same time, I found my uniqueness challenged by having a twin brother who looked, acted, and played chess a lot like me. One of the many gifts my twin brother has given me (in addition to the cuff links—thanks, Alan!) was the opportunity to confront my sense of uniqueness, to think more carefully about it, and to feel sonder even before I had a word for it.

It may be harder to appreciate the uniqueness of others. In part, the difficulty is simply apprehending all the ways that others can differ. Sonder also seems antithetical to the psychological principle called the false consensus effect, the tendency to assume that others share our beliefs. Perhaps because of our human need for community and belonging, we may overestimate the similarities between others and ourselves. Sometimes that may be good; at other times a dose of sonder might be the best prescription for connecting even more to others. Uniqueness may be an important feature we have in common.

My takeaways from this new word for a common feeling? First: Just having a word helps me think about this feeling and its relationship to other aspects of existence (thanks, John!). Second: One of our goals for teaching might be to help students counter the false consensus effect by developing their sonder experiences and balancing their feelings of uniqueness and similarity. Third: Tomorrow, I start looking for “Better Lectures Coffee & Tea.”