An Oral History of the First U.S. Ascent of Annapurna (Oh Yeah, and It Happened to Be the First Female Ascent, Too)

In 1978, a historic expedition put the first women—and first Americans, period—on the summit of Annapurna, the world’s tenth-highest peak. Despite their triumph, the deaths of two climbers stirred controversy. In an oral history weaving together the perspectives of key team members, Sherpa high-altitude staff, admirers, and critics, Katie Ives discovers that debate still lingers—as does the expedition’s power to inspire.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

On October 15, 1978, Vera Komarkova, Irene Miller, Chewang Rinjing Sherpa, and Mingma Tshering Sherpa stood in a dazzle of afternoon light on the summit of 8,091-meter Annapurna. Around them, only the tallest snowy peaks of the Nepalese Himalayas crested the blue haze. There was a chill in the air, a foreboding of winter storms. Wind rattled the bright colors of the flags they placed: one for Nepal, one for the United States, and one with the slogan of their expedition: “A Woman’s Place Is On Top.”

The XX Factor Issue

Our special issue highlights the athletes, activists, and icons who have shaped the outside world.

Our special issue highlights the athletes, activists, and icons who have shaped the outside world.It had been 28 years since French climbers Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal became the first to reach the summit. Now, Komarkova and Miller had become the first Americans and the first women. Theirs was only the second ascent of the Dutch Rib, a bladelike ridge of blue ice surrounded by hanging glaciers and avalanche-pummeled slopes that only a few people have ever successfully climbed.

The American Women’s Himalayan Expedition, as it was officially called, took place during a decade when many of the barriers that restricted women’s legal freedoms were on the verge of shattering. Legislative acts and court rulings were rapidly expanding women’s rights in the United States, setting off nationwide debates about traditional distinctions between male and female roles. A few years after the enactment of Title IX prohibited gender discrimination in federally funded education programs, the numbers of female high school athletes grew by nearly a factor of five. In 1972, tennis player Billie Jean King became Sports Illustrated’s first female Sportsperson of the Year. More than ever, the world of athletics seemed a metaphorical stage on which women could prove their equal worth.

A Woman's Place Is On Top

Back when men still believed the “weaker sex” were inferior climbers, Arlene Blum led an all-women’s ascent of Annapurna, the world’s tenth-highest peak. Listen to why the expedition continues to inspire climbers and stir debate.

Back when men still believed the “weaker sex” were inferior climbers, Arlene Blum led an all-women’s ascent of Annapurna, the world’s tenth-highest peak. Listen to why the expedition continues to inspire climbers and stir debate. Until the mid-seventies, however, the summits of the 8,000-meter peaks of the Himalayas seemed to exist beyond an unbreakable glass ceiling. Denunciations of ambitious female climbers punctuated the outdoor media of the day as male pundits argued that women didn’t have the strength or skill for high-altitude mountaineering, or that feminist motives pushed them to take unnecessary risks. In 1959, when the great French alpinist Claude Kogan and her Belgian climbing partner Claudine van der Straten-Ponthoz died attempting 8,188-meter Cho Oyu, British reporter Stephen Harper insisted on “a verdict that even the toughest and most courageous of women are still ‘the weaker sex’ in the White Hell of a blizzard and avalanche-torn mountain.”

By 1978, women from Poland, Japan, and Tibet had succeeded in climbing several 8,000-meter peaks, including Mount Everest and Gasherbrum II. Still, the Annapurna climbers were keenly aware that their performance might be judged as a measure of women’s potential. Four years prior, after the deaths of eight Russian women on 7,134-meter Pik Lenin, Mountain magazine had declared, “Perhaps [the accident] reflects … unfavorably on the concept of women’s equality.” Then, only days after their team’s historic achievement on Annapurna, members Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz and Vera Watson fell to their deaths while making their own summit attempt. Runners carried the message of both success and loss down steep trails to the village of Pohkara. From there they caught a ride to Kathmandu, where the news was wired to families, friends, and journalists. The American survivors returned home to a maelstrom of admiration and controversy, echoes of which reverberate to this day.

Since the expedition, three more members—Komarkova, Joan Firey, and Liz Klobusicky-Mailänder—have died, away from the mountains. Here many of the expedition’s surviving members and Sherpa high-altitude staff, as well as several writers and critics, reflect on a story that continues to offer contrasting visions of what it means to call a mountain a woman’s place.

Origins

The idea began in 1972 as various international expeditions converged on the summit of Noshaq, a 7,492-meter peak in Afghanistan. Clambering over loose stones toward her team’s high camp, 27-year-old Arlene Blum, a biophysical chemist from Berkeley, California, saw the legendary Polish mountaineer Wanda Rutkiewicz appear through a haze of falling snow. Rutkiewicz was returning from the summit, where she and her female partners had just set an altitude record for Polish women. She embraced Blum and declared, “Now we must climb to 8,000 meters together, all women.” Back at base camp, Blum met with Rutkiewicz and one of her teammates, Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz, a British woman who lived in Poland, and the three began discussing the possibility of a women’s expedition to an 8,000-meter peak.

By then Blum had experienced the backlash against women’s entry into male-dominated fields. In 1966, when she was a graduate student at MIT, a potential research adviser told her that he thought it was “a waste of time” for her to try to get a Ph.D. in physical chemistry. Three years later, the organizer of a commercial Denali expedition informed her that he wouldn’t allow female clients above advance base camp. In both cases, Blum persistedobtaining her Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of California at Berkeley in 1971 and coleading the first all-female ascent of Denali in 1970.

In 1976, Blum participated in the American Bicentennial Expedition to Everest, an experience that one of the men on the team, Hans Bruyntjes, described as being marred by “male chauvinist traits.” On her way home, disillusioned, Blum stopped at the Ministry of Tourism in Kathmandu, where she applied for a permit for an all-women’s expedition to Annapurna. A few months later, back in California, she began assembling a team.

ARLENE BLUM (expedition leader): It wasn’t that easy to find women mountaineers in those days. It sounds glamorous to go to Annapurna, but it’s hard work. I looked for common sense, calmness, that steadiness and determination to be able to slog up a mountain.

CHRISTY TEWS (38-year-old base-camp manager): I was raised in a good Iowa household where women did women’s work and never asked anything for themselves. One day my daughter and I camped in some California beach park, and I went for my evening run, and all of a sudden comes this message in my head: What you need is the company of strong women. Later, I drove down to Palo Alto, and I ended up at Vera Watson’s house. I just crashed the Annapurna meeting. That was the draw—to find places with each other without any interference or opinions or sexual politics with men.

JANUSZ ONYSZKIEWICZ (Polish climber and husband of the late Annapurna team member Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz): Certainly Alison was one of the best women climbers of her day. Especially at high altitude. She could provide a calm atmosphere of reassurance. She was quite taken by the whole idea of women’s climbing. The women we climbed with were mature enough not to rely in any way on men.

ANNIE WHITEHOUSE (21-year-old team member from Wyoming): People ask me a lot if I’m a feminist. I’ve thought about it, and my answer is, I’ve always been a feminist by definition, but not the 1970s definition. Seventies feminism seemed brittle to me, because it was defined too small. There wasn’t a lot of thought about women in developing countries. My sensibilities were always against people who would take advantage of someone because of race, sex, culture, or socioeconomic status.

MARGI RUSMORE (20-year-old team member from California): I grew up in a progressive family, with lots of kids who were treated in a pretty egalitarian way. I was really surprised by the attitudes we ran into. On a personal, visceral level, I thought that the whole idea that women couldn’t do things in the mountains was inane.

IRENE MILLER (43-year-old team member from California): There were some men who would never have allowed us to go on a trip, or if they did, they would just sit there telling us what to do. I was concerned about going when all my kids were young. But I knew that when we summited, a message would go out. They would know that at least we were OK.

WHITEHOUSE: Women get so doubted when they leave their kids at home. There have been so many men who have gone on expeditions and long, demanding climbs. But with them, people will say, “This guy has got this great support at home, and that makes it all the better.”

DYANNA TAYLOR (26-year-old filmmaker from California): I wouldn’t ever be asked to come on a male expedition. I was aware of the National Organization for Women at the time, of Gloria Steinem. There was a change coming. But there was a lot of lag that hadn’t caught up yet. The television networks were all very male-bound sports centers. When we approached them about making a film, the line that came back was, “Oh, these are women. They’re not going to bring back more than home movies.”

Preparations

Most of the $80,000 required to fund the trip came from the sale of 15,000 T-shirts with an attention-grabbing slogan: A WOMAN’S PLACE IS ON TOP. For some supporters, the shirts reflected an emerging zeitgeist in which it seemed that strong women might rise to the highest places in both the mountains and society; for others the implied sexual humor proved irresistible.

BLUM: When I went on expeditions with guys, they often had offices and secretaries. We did the fundraising all by ourselves, with anyone who showed up

and volunteered. We had this house on Indian Rock Road in Berkeley with Christy’s trailer parked in the front yard. It was T-shirt central.

TEWS: I worked part-time in San Francisco plumbing old houses. The rest of the time I sold T-shirts. I went off across the country to these trade shows. We had the shirts that said A WOMAN’S PLACE IS ON TOP, and then we had shirts that just said ANNAPURNA, because some members of the expedition were embarrassed by the double entendre. People had their own personal reasons for wanting one of those T-shirts. These big men would walk over and look me up and down and say, “Yeah, honey, I want one of those.”

WHITEHOUSE: I didn’t like to wear the T-shirt at that time. At those fundraising parties, you’d get weird guys who would try to put sexual innuendo on that logo. And I was not comfortable trying to fend them off.

TAYLOR: When I think about the slogan, what comes to mind is this busting out—a latent voice suddenly being shouted from the mountaintops: “A woman’s place is on top, and we’re going to make it to the top of this mountain!”

By August 1978, only eight climbers had ever stood atop Annapurna. Nine climbers had perished while climbing. And there were still just three established routes to the summit. In the end, Blum settled on the little-known Dutch Rib on the north face, pioneered scarcely a year before, in October 1977, by 11 Dutch climbers and nine Sherpa staff. Dutch team leader Xander Verrijn-Stuart would later describe the route in the American Alpine Journal as a “safe” alternative to other, more hazardous ways up that side of the mountain. Blum and her team would soon find out otherwise.

BLUM: Annapurna was the first 8,000-meter peak climbed. It was one of the lower ones. I didn’t have a clue how dangerous a place it was: it didn’t have enough history. Our reconnaissance was in December 1977, when everything was frozen solid. If I’d realized how bad the avalanches were at other times of the year, I like to think we wouldn’t have gone there.

LHAKPA NORBU SHERPA (21-year-old staff member on the 1977 first ascent of the Dutch Rib, who later joined Blum’s expedition): Those avalanches were obviously very scary, and those risks forced us to climb along a ridge that was also dangerous, since it gets windy.

MICHAEL KENNEDY (former editor in chief of Alpinist, who attempted the Dutch Rib in 2000 with Neil Beidleman, Veikka Gustafsson, and Ed Viesturs): The scale of Annapurna’s north face is something that’s really hard to wrap your head around until you’ve actually been there. You have to be a pretty confident ice climber for the Dutch Rib. But really, the daunting thing is just how big the face is. It’s the kind of terrain that if you fell and you were on hard snow, you’d go for a long ride.

By the mid-seventies, alpine-style climbing—small groups moving fast and light with no supplemental oxygen, high-altitude support staff, or fixed ropes—was just beginning to spread on 8,000-meter peaks. Blum settled on a more traditional siege approach, which required a team to haul huge quantities of food, fuel, and gear up to a series of camps.

The decision meant that the team faced early conflicts about the practical application of their ideals: What did it mean that they were basing their expedition on tactics that men had imported from the military in the 1920s? For climbers of all genders, the counterculture movement of the seventies stirred resistance to older traditions of swearing loyalty to a single authoritarian leader. Aware that team cohesion would be essential, Blum arranged for the group to meet with a psychologist, Karin Carrington. At one session, climber Joan Firey said she didn’t completely trust Blum’s ability to lead. Others said they hoped she would be a “decisive” leader, but also one who operated according to an inclusive, consensus-based model.

BLUM: There’s a lot of individualism in climbers. I thought that women would have less, but everybody who wants to climb a mountain like Annapurna has a lot of personal drive.

TEWS: There were stories about men on expeditions who never spoke to each other again in their lives. And that was one thing we truly wanted to avoid.

BLUM: Maintaining our friendships was as important as climbing the mountain.

KARIN CARRINGTON (team psychologist): There was a lot of grappling with, What is an alternative way of leadership that draws on the strengths of women to be more collaborative and at the same time provides the security of a decisive voice—in this case, Arlene’s—to make the calls in extreme circumstances? How does Annapurna become a woman’s place and not just a replica of expeditions that have been all-male in the past?

TAYLOR: Some of us wanted to be totally independent of men and the leadership styles of men. But there wasn’t much documentation we could fall back on. The expedition format was designed by men.

RUSMORE: If the state of climbing had been such that alpine style was the norm in 1978, it would have been a different climb. But Arlene wanted to be sure we were successful. We were already breaking the norms of mountaineering at the time. Maybe not taking on everything was a good idea.

TAYLOR: For some of us, the effort to bring things to the surface and to process as we went was necessary. Others loathed it. Arlene was desperately trying to hold open the door to a democratic, inclusive process.

Maintaining our friendships was as important as climbing the mountain.

Like many leaders of 8,000-meter expeditions, Blum also decided to hire Sherpa staff, believing that their assistance would increase the margin of safety. By doing so, however, she knew that she might incur criticism that her team was relying on help from men. Back then there were very few Sherpa women with highaltitude mountaineering experience. Blum had hoped to employ female lowaltitude porters and to train them to climb, but she was disappointed to learn that the sirdar had instead chosen two women—Pasang Yangin Sherpa and Ang Dai Sherpa—to be kitchen assistants.

Among the Sherpa men who ended up working for Blum’s Annapurna expedition, some welcomed the presence of Sherpa women. Others felt uneasy about it, concerned that the women might supplant the male staff on the mountain. Eventually, Blum gave up trying to teach the Sherpa women high-altitude climbing skills and sent them home early. Pasang Yangin and Ang Dai left angry over the loss of employment.

BLUM: I liked the idea of having Nepali women as team members and having our Sherpas be women. However, the Sherpa union did not want that at all. There were women hired, but they were really hired to do things like laundry and dishes, not to climb. Now, of course, there are Nepali women’s expeditions. But the idea was probably ahead of its time for Nepal in the mid-seventies.

WHITEHOUSE: The Sherpa women were put in a difficult position, because they were picked out to excel but they didn’t have the background yet, the climbing ability. Arlene wanted them to be different—or to perform differently than they were able to. I think she was generally good about trying to consider Sherpas members of the team, although it’s always different when someone’s getting paid.

LOPSANG TSHERING SHERPA (38-year-old sirdar): I was happy to be offered the job of sirdar, but my happiness had nothing to do with the fact that it was a women’s expedition. It was an opportunity to earn money. I knew that women who came to climb in the Himalayas were trained climbers. There was snow and ice where they came from, too.

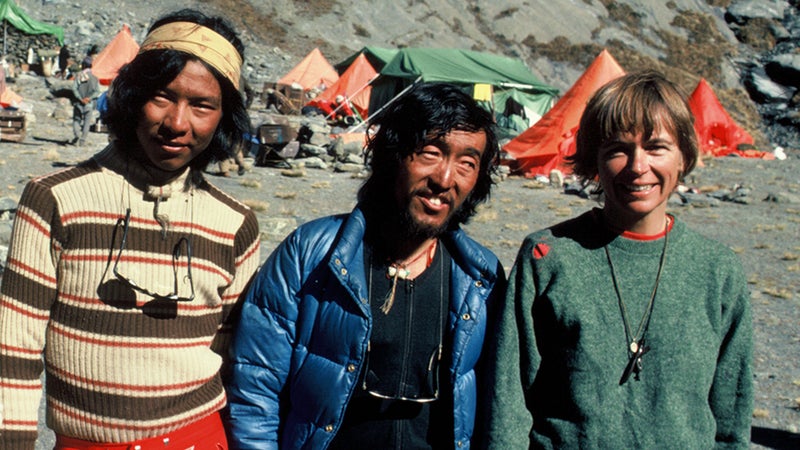

CHEWANG RINJING SHERPA (32-year-old high-altitude staff): When I looked at the foreign women, I didn’t feel confident. I told Mike Cheney [Blum’s Kathmandu-based expedition outfitter] that I wasn’t sure they would make it to base camp. He got angry. “Would they have come all this way if they can’t climb mountains?” he said. I kept quiet after that.

MINGMA TSHERING SHERPA (24-year-old high-altitude staff): I always thought about the risks of going to a mountain. Whether the expedition would be different or whether the climbers would be able to make it to the summit—I never thought of these things beforehand. They were a group of mountaineers, as simple as that.

The Climb

On August 16, the team began the arduous ten-day trek from Pokhara to base camp. More than 200 low-altitude porters helped transport some 12,000 pounds of supplies through 80 miles of leech-filled rainforest, steep muddy hillsides, and deep mountain gorges. After the team arrived in base camp on August 26, they began hearing cracks of ice calving up high on the mountain, setting off giant avalanches down the north face. On September 26, a massive avalanche swept toward the glacier above camp one, where Taylor and Ashton were filming, along with Tews, Firey, and expedition workers Pemba Sherpa and Durga “Kaji” Shrestha.

TEWS: At first I thought, Oh boy, this is great. We have an avalanche coming down and Dyanna can film it. It took me about 30, 45 seconds to realize that we weren’t just going to watch this avalanche. We were going to participate in this avalanche.

TAYLOR: The avalanche was blowing toward us at what seemed like 100 miles an hour, and poor Christy and Joan were just screaming at us to get down. When it hit us, I was lifted and tumbled with incredible force. All I could think was, Keep your arms in front of your face so you can create an air space. Try to figure out which way is up. Everything got dark, and I thought I was buried forever.

The climbers and staff emerged from the clouds of debris shocked but uninjured. A narrow snow bridge had stopped Taylor from falling all the way to the bottom of a deep crevasse, and Ashton was able to help her clamber out.

BLUM: I wasn’t sure we should be there. If the team had wanted to turn back, I would have said great. But they really were determined.

MILLER: We couldn’t decide to quit. I felt the upper part of the mountain would be safer.

CHEWANG RINJING: I wasn’t too worried about the avalanches. I carried rice grains blessed by high lamas. I sprinkled these grains all around my tent. The power of the grains diverted avalanches away from my tent.

MINGMA TSHERING: You always wondered whether you would make it back from a mountain. My wife was pregnant when I left. Our son was born while I was on Annapurna.

As with all siege-style ascents, the climbers spent weeks fixing ropes and shuttling loads—increasing the length of their exposure to the long-term effects of altitude and the continual hazards of falling ice and snow. From August 28 to September 12, they carried supplies to camps one and two through a labyrinth of crevasses. Then they traversed the avalanche zone below the infamous Sickle Glacier to reach a steep crest of rippling blue ice. Firey, who had been ill for weeks, recovered just enough to assist in hauling the heavy loads, remaining determined to support the team. (Soon after she returned to the States, she discovered she had terminal cancer.)

Blum intended to assign the next leads to the team’s best ice climbers, but when she announced her choice of Alison ChadwickOnyszkiewicz, Vera Komarkova, Liz Klobusicky-Mailänder, and Piro Kramar, with Sherpas in support, other members protested. Vera Watson called the decision undemocratic. Irene Miller, upset at the dissension, offered to quit. Ultimately, nearly everyone got a lead, but some climbers, including Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz, appeared impatient with the overall strategy.

RUSMORE: Alison might have been ahead of her time in a lot of ways. She probably would have thrived on an alpine-style climb more than siege style. She didn’t want to have this lumbering beast that was the expedition. She was 36, in peak climbing shape. She was like, “Let’s just get up there.” And maybe that would have worked. We had a lot of good climbers. But that wasn’t the plan.

TAYLOR: There’s an incredible geometry to load carrying and parsing out all the supplies, making sure it’s working. It was extraordinary to see the culmination of all this planning playing itself out with physical bodies on the side of the mountain—women’s bodies.

RUSMORE: Carrying the loads from camp one to camp two, you’d have to jump over really large crevasses. You didn’t want to screw up and not make the leap. Those were big packs—45 or 50 pounds. It wasn’t technically challenging, but finding enough strength—that was hard.

CHEWANG RINJING: The section of blue ice between camp two and camp three proved a major hurdle. I had to climb an overhang one step at a time to fix a rope. The face of the overhang was smooth as glass. I told the Sherpas that they needed to be braver if they were to succeed. Wangyel retorted, “I have a family back home. What if I fall down and break a leg trying to be braver? You think these women can rescue us?”

WHITEHOUSE: I saw how Mingma and Chewang were two of our team’s more motivated Sherpas. I was as happy with them as I was with any other partners. We were all fighting for who got to do the leading. I don’t think I had ever put in an ice screw on lead before. It was tricky route finding. I remember watching Liz. She was cool, calm, collected—just like I wanted to be.

RUSMORE: Being in that vastness for a long period of time works on you. I spent 32 days at camp two or higher. When you’re at that elevation, there’s nothing. Just snow and ice. You don’t hear much except for the avalanches. Oh, we’ll climb at night if the avalanches are bad during the day, we thought. But hell, there were avalanches coming down at two in the morning.

From September 27 to 28, most of the Sherpa high-altitude staff went on strike over their equipment. After Blum offered to pay them bonuses, they returned to work. By October 8, the expedition had fixed ropes to the top of the rib and established camp four at around 7,010 meters. They would place camp five at about 7,400 meters as the summit launch point. Feeling pressured to ensure that the initial group reached the top without men, Blum announced that the first summit team would consist of three women but no Sherpas. The second would include two Sherpas and two women. There would likely be only enough supplemental oxygen for the first team.

BLUM: I had been on other trips where there was a lot of competitiveness around being a member of the summit team. I liked the idea of everyone sharing the summit more. I wanted to think that Annapurna would be like that. But I remember Irene telling me that somebody had given her advice on how to politic to be on the summit team from the beginning.

RUSMORE: As we had the conversation about who was going to be on the first summit team, there was certainly some vying for position. It seemed that it was coming down to either me or Irene for one of the slots. I told Arlene, “I’m really strong. I’ll make a second summit attempt. Besides that, I just turned 21. If I want to get to the top of a big mountain, I can do that. Irene’s 43.”

MILLER: I really wanted to get a chance to go high—to complete something I had wanted to do when I was younger.

WHITEHOUSE: I can’t say I felt a strong desire to get to the summit myself. Every step along the way was an adventure for me. Summit or death—we didn’t have that macho kind of thing. But there were summit politics, and I was oblivious to that.

RUSMORE: Arlene listened to everyone first, but at some point she had to say: “This is what we’re doing.” I get concerned when people say this is a feminine leadership style, very consultative. I don’t think what we see on that climb is about the leadership style of women as much as it is about the leadership style of Arlene. Arlene is unique. It’s beyond gender.

It was extraordinary to see the culmination of all this planning playing itself out with physical bodies on the side of the mountain—women’s bodies.

Ultimately, Blum chose Miller, Komarkova, and Kramar for the summit. But as high winds battered the upper slopes, Blum told Miller she could bring one of the Sherpas along. By the evening of October 14, Miller, Komarkova, Kramar, Mingma Tshering, Lhakpa Norbu, and Chewang Rinjing were at camp five. Kramar, suffering from frostbite on her finger, decided to remain there. Lhakpa Norbu had a headache, but the other two Sherpas wanted to summit, and Miller and Komarkova agreed they could. The Sherpas broke trail over crusted snow and deep drifts. In the American Alpine Journal, Komarkova later recalled that when she offered to take a turn in the lead, Chewang Rinjing began moving faster.

MINGMA TSHERING: We started around 6:30 a.m. I broke trail almost halfway to the summit, until I could not do it anymore. After that, Chewang took over.

MILLER: Almost right away we started having trouble. I’d take one step up and slide back seven-tenths. It wasn’t agony, but it was challenging. Vera decided to use oxygen. Mine didn’t work right away. The Sherpas fixed that pretty quickly. Chewang was encouraging, telling me repeatedly, “Slowly going, summit.” But the climb went on and on.

CHEWANG RINJING: The weather was perfect. I was a little ahead of the other climbers. Mingma and I were climbing without oxygen. Near the summit, you could look down and see the teahouses in the Annapurna Sanctuary. I called out to the others to hurry up so they wouldn’t miss the view.

MILLER: There were five little tiny summits, all about the same height. At first we weren’t sure where the real one was. Everything was beautiful. There was a breeze coming over the top. Of course, it was a great joy to be there, in more ways than one. You weren’t going to have to go uphill anymore. I had a sense of finishing what I set out to do.

CHEWANG RINJING: It was a feeling I had never experienced before. I was so happy, so relaxed, that I felt I would forget even my wife and children for a moment. I knew that finding work on expeditions would become easier after reaching the summit. I was very happy to have another Sherpa with me. Mingma and I had shared a tent during the entire expedition. We became like family.

TEWS: I was at camp two, as were many of us, and through binoculars we could actually see them climbing to the summit. And then they stopped moving, and at that point we knew they’d made it. It was really breathtaking. I was the base-camp manager. But for me there was a feeling

of, We all did this.

TAYLOR: My camera had the closest view because of the powerful lens I was using. There was this huge plume coming off the top. I couldn’t tell who was who. I felt great relief that it was all four of them, which meant that all four were safe at that point. They still had the descent, but they were standing there.

CHEWANG RINJING: We had problems coming down because the snow had melted, and chunks of it stuck to our crampons. So we had to stop every two steps and shake off the snow.

MILLER: Pretty soon the oxygen ran out. It was just beginning to turn dark as we got into camp. I fell down behind the tents, landed on my back, and I was laughing.

RUSMORE: I was touched to get a piece of the limestone from the top. Chewang brought down rocks for everybody. He sought each of us out and gave them to

us individually. It was sweet and thoughtful, and I still have mine.

Blum had initially suggested that Chewang Rinjing, Mingma Tshering, Whitehouse, Rusmore, Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz, and Watson form the second summit team. Yet, as Whitehouse recalls, the logistical pyramid of the siege began falling apart: Chewang Rinjing and Mingma Tshering, who now had frostbite, had already summited, and along with Lhakpa Norbu, Miller, and Komarkova, they were too exhausted to support another effort. Rusmore had frozen her feet while establishing the route to camp five. Kramar had frostbite. Ang Pemba and Lopsang Tshering were ill.

Nonetheless, Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz and Watson still hoped to make a second summit attempt—this time, perhaps, by a direct new variation, without Sherpa support, to the then unclimbed 8,051-meter central peak. Having failed to persuade Whitehouse to go with them, Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz and Watson started up from camp three to join Wangyel, who was supposed to accompany them as far as camp five.

On October 17, Wangyel felt sick and headed down. Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz and Watson continued their ascent alone. There was no one left to wait for them at a high camp to help if anything went wrong.

TAYLOR: I think Alison knew that she needed someone as strong as Annie or Margi. It was a compromised second attempt with just Vera Watson.

WHITEHOUSE: I had been on other climbs with Vera Watson and Alison before, and they were always super strong and really good at decision-making. But I think we were all getting exhausted. I said, “I don’t think you guys are really moving that well.” They vehemently denied that. That was a clue to me that we weren’t seeing things the same. So I said I’d just wait for them.

LOPSANG TSHERING: Arlene and I tried to convince Alison and Vera Watson that it was not necessary for them to attempt the summit—the mountain had already been climbed, and the Sherpas were not well.

MINGMA TSHERING: They asked me to climb with them, but I told them I couldn’t because my toes were getting numb. I even suggested that they drop the idea. But they would have none of it.

BLUM: Alison adamantly wanted her attempt. She had wanted it to be all women. I felt I didn’t have the right to tell them not to go. I just remember feeling that we’d already achieved our goal. The team goal. The longer we stayed there, the more dangerous it was. Which ended up being true.

JANUSZ ONYSZKIEWICZ: Alison was a purist, partly a result of her experience in the Hindu Kush and the Himalayas, where we climbed without the assistance of highaltitude porters. She was determined that women should not be just an addition to male climbers who lead.

RUSMORE: In the debates about whether to go to the summit, Vera said she didn’t want to disappoint Alison. That’s probably not true. If she really didn’t want to go, she wouldn’t have gone. She was no pushover. Vera was a strong climber, and this was her last expedition. She wanted to make it.

That night, Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz and Watson failed to make their scheduled radio call. Over the next couple of days, Blum urged the Sherpas to go look for them, while Mingma Tshering responded, “Our feet are still frozen. We’re too tired.” But on the third day, they agreed to try.

BLUM: I wanted someone to go. But again, it’s dangerous. My leadership style was not to order people, but to have them do what they felt comfortable doing.

LHAKPA NORBU: Mingma and I spent a lot of time together with the women, and we got to know each other well. But it was windy, and the route was really bad. Perhaps part of the reason that we decided to go was a feeling of guilt that we hadn’t gone up with Alison and Vera Watson. We found them a little below camp four. One had fallen into a crevasse and the other had got stuck outside. They were still connected with a rope. Nothing stands out in my memory from Annapurna except seeing those bodies.

TAYLOR: My camera was the first to finally spot Alison’s red parka after the Sherpas came down. It was devastating.

BLUM: Nobody will ever know really what happened. I always say that there could have been a little avalanche or rockfall, or somebody put their foot in the wrong place. You don’t know what caused the fall.

RUSMORE: I’m not going to sit here and try to reconstruct their mindset. Nor am I going to say should have, could have, would have. I wouldn’t do it after the climb. I won’t do it 39 years later. They were both competent climbers. It wasn’t a foolhardy decision. It was just a climbing decision that didn’t work.

CHEWANG RINJING: I often remember Vera Watson. She treated me like family. It feels like her words will stay with me even in my next life.

ONYSZKIEWICZ: I was on a Himalchuli expedition at the time, and I got a letter. It seemed curious that it was from Arlene, not from Alison. Only after reading the whole letter a second time—that’s how it came to my consciousness, what Arlene was telling me. That Alison had died.

The Aftermath

Before their departure from the mountain, the expedition members carved Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz’s and Vera Watson’s names into the memorial stone near base camp. At dusk, below the clouded peak, the women sang the Shaker song “Simple Gifts” and with the Sherpas chanted “Om mani padme hum.”

Back in the U.S., several team members were invited to the White House for a reception with President Jimmy Carter’s adviser on women’s affairs, Sarah Weddington. The New York Times hailed the climb as an “inspiration to women.” Controversy erupted soon after, with critics questioning their decision-making and claiming that the presence of Sherpa men negated the idea of a women’s ascent. A letter sent to National Geographic, signed with the name Melinda Sanders, sought to stop the publication of Blum’s article on the climb. (Sanders later explained that the letter was written by her then-boyfriend, mountaineer and photographer Galen Rowell.) “Had the men on Annapurna been Americans instead of Nepalese, no one would have gotten away with a claim that this was an achievement by and for American women,” the writer declared. National Geographic went ahead with Blum’s story, but she remained shaken.

In 1981, Outside published a feature on women’s alpinism by David Roberts. He criticized Blum for relying on exhausted and frostbitten Sherpa men for the search, and he questioned the cultural awareness of her treatment of Sherpa women. Roberts hoped that his article would be read as an examination of the hazards of directly mixing politics and climbing. But the editors added the heavy-handed cover line “Has Women’s Climbing Failed?” and an internal headline that asked, “Why has the course of women’s mountaineering led to tragedy?” (which Roberts felt distorted his intent).

Despite all the debates, Blum’s popular 1980 book, Annapurna: A Woman’s Place, depicting the immense barriers the women faced, became a catalyst for many female alpinists. As the accomplished climber Kitty Calhoun recalls, “It made a statement other people could build off.”

TEWS: I did a slide show at a college in Sioux City, Iowa, after the expedition. When I finished, a woman walked up to me. She was probably close to my mother’s age. She’d spent her whole life cooking and cleaning and raising children, and I admired her for that. I had this instant recognition: she looked like I would have looked if I had continued to be an Iowa farm wife. She said to me, “You know, I’ve always wanted to climb mountains.” And it just—it pierced me to the core.

TAYLOR: It was so discouraging to have members of the climbing community reject us, saying things like: “There weren’t any men who supported Alison and Vera Watson, and that’s why they died.” Or: “Well, you’re a women’s expedition. You shouldn’t have male climbers with you. Were the Sherpas dragging you up the mountain?”

RUSMORE: I think the response that our expedition got generally reflected changes going on in how we as a culture viewed women. Women were having a little success climbing, and it was starting to make men nervous. It was as if they thought, You girls can climb, but don’t take on the biggest mountains. You leave those for us. That article in Outside kept me from reading the damn magazine for 36 years. It was a successful climb. We raised the money we needed. We all got along. If this had been a men’s climb, they would have been saying it was fine. But women aren’t allowed to get killed.

DAVID ROBERTS (writer): I thought of myself as supportive of feminist causes. After Vera Watson and Alison died, Arlene sent Sherpas up to try to reach them and, if possible, retrieve their bodies. That was extremely dangerous. To me it proves that, in a crunch, when things got really desperate and serious, Arlene defaulted to the men of the team. Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz was the one who really wanted to get to the summit without Sherpas. If you want to make a statement, then do it that way. But I don’t think anybody would say that it was a failed expedition. They got to the summit after all. It was star-crossed.

JULIE RAK (University of Alberta professor, currently writing a book on women’s mountaineering history): If Alison had succeeded in completing that first ascent of the central peak without Sherpa support, I think there would have been more than one version of the Annapurna story. I suspect that could have created a different kind of women’s Himalayan climbing earlier, like the kind that happened in women’s rock climbing when Lynn Hill freed the Nose. Alison was unusual, not just because of her early commitment to alpine style. She had it in her to be innovative.

HILAREE O'NEILL (first woman to climb Everest and Lhotse in a 24-hour period): I still think there are a lot of barriers to entry for women mountaineers. But I believe the stories that come out of adventure writing are influential to other women. There’s a lot to be said just for breaking the mold. It’s a slow process of change in a narrative that’s been ingrained for more than 100 years.

In the final cut of the expedition documentary, which aired April 13, 1980, in ABC’s American Sportsman series, the summit-day footage shows four small dots flickering near the apex of Annapurna, but the movie’s voiceover mentions only the women’s historic achievement.

MINGMA TSHERING: I was disappointed by how little there was about us, our work. There were no images of us fixing ropes between base camp and camp five. But it’s the past now.

LOPSANG TSHERING: Yes, Sherpas did fix some ropes, but it’s not true that they were the only ones who did those tasks. They were very strong women, those climbers. They have mentioned our names. That is enough for me.

RAK: Men’s national expeditions also got talked about that way. With the “French ascent” of Annapurna in 1950, well, there were people up there who weren’t French. There were Sherpas, but they were never part of that terminology. That’s one of the problems of feminism in the period. It takes on older, male paradigms and doesn’t interrogate them fully. And because it doesn’t, it repeats a lot of their assumptions.

TAYLOR: We felt Mingma and Chewang, who we’d come to care about, should be identified in the summit scenes. But, of course, ABC wanted to minimize the men in the story. It was much more heroic for them that way. Today I’d make a completely different film. I’d be much more interested in looking at the Sherpas’ lives and talking about their incredible gifts in mountaineering and the relationships that formed between us. I remember when we hiked out, how powerful it was to dance with the Sherpas every night by the fire. They included us, teaching us the simple steps. All of us were grieving.

SHAWNTÉ SALABERT (senior writer at Modern Hiker): One day in 2008, I came across a book called Annapurna: A Woman’s Place. It was an odd size, a strange blue color, and I got completely lost in the story. This was the first time I’d ever read an adventure book in which women were the protagonists. The overriding feeling I had was one of possibility. It made me want more. What I would like to see on bookshelves now are stories from people of all sorts of backgrounds, people who face gender barriers but also financial barriers, racial or cultural barriers. It’s going to take a while for adventure writing to become more diverse in a really meaningful way, to untangle this web that’s been woven over so many years of what mountaineering looks like.

As the number of surviving expedition members has decreased over the decades, the team now holds frequent reunions.

BLUM: We love having our reunions. I always say we feel like we’re back on the glacier.

TAYLOR: It’s like we’re this family. We cook. We talk. We laugh. Those experiences are embedded in our sinews. What I trusted so deeply on Annapurna were these women who taught me how to rope up. There was something beautiful about seeing a woman up ahead of me, carrying a very heavy load.

TEWS: Women in our culture don’t often get to bond like that. Men go to war and do it, but women don’t often get the opportunity. To stand in the face of death together gives you something that you don’t get very many other places. My life is in her hands and her life is in my hands, you think. Now, how much more profound can it get than that?

MILLER: Annapurna was hard to get over. I would say to people, when they asked me if I’d do it again, No, but I would do it for the first time again.

TAYLOR: I go back to the beauty of the mountain. On certain days we could bathe in a mountain stream. We did it out of sight of the Sherpas. I remember the power of that mountain, the grayness and the heaviness and the angularity of it. The ice and the rock and then these beautiful female forms.

Katie Ives is the editor in chief of Alpinist Magazine. Additional reporting by Kapil Bisht and Karsang Sherpa