On Tuesday, water pouring into the Lincoln Tunnel connecting New York City and New Jersey necessitated emergency maintenance and prompted a social media blowup when video of the rushing water was posted to Twitter.

The water spilling over the Lincoln Tunnel walkway was caused by a water main rupture in a facility room, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates the tunnel, told an NBC affiliate in New York. Water was pumped back out of the tunnel after the break was repaired and normal traffic flow resumed the same evening. While contacted by phone for details, the Port Authority did not provide additional information regarding the incident to Newsweek prior to publication.

Who has “Lincoln Tunnel leak” on their 2020 Bingo card? pic.twitter.com/381QfE29zC

— InMinivanHell (@inminivanhell) July 15, 2020

A frightening sight to onlookers and catastrophizers on social media, the Lincoln Tunnel leak may have been a relatively minor incident, but also reminded people of the astounding physical feat embodied in driving through a tunnel 97 feet beneath a river. Building the Lincoln Tunnel was a herculean project, which posed far more danger to its builders than getting their tires wet.

Construction on the Lincoln Tunnel began in 1934, with the first of two planned tubes completed in 1937. The second tunnel opened in 1945, but the explosion of two-way traffic—21 million cars passing through annually by 1955—led to the construction of a third tube. An article in a June 1956 Schenectady Gazette celebrated the completion of the third tunnel, while also noting the construction's cost in lives.

"The new 100 million dollar third tube of the Lincoln tunnel was officially 'holed through' today with a flourish of bolt tightening," the article opened. "The 5,486 foot tube was completed in 20 months without the loss of a single life—a rarity but not a record. The Queens Midtown tunnel under the East river was completed in 1940 without a fatal injury. However, 15 sandhogs died building the original two Lincoln tubes."

While both New York and New Jersey governors took part in the ceremonial tunnel completion, the actual work of constructing the three tunnels was performed by skilled "sandhogs," who began work on the tunnel after tense negotiations (including strongarm tactics from the New York Police Department) between 32 affiliated unions and the tunnel's contracting agencies, narrowly averting a general strike.

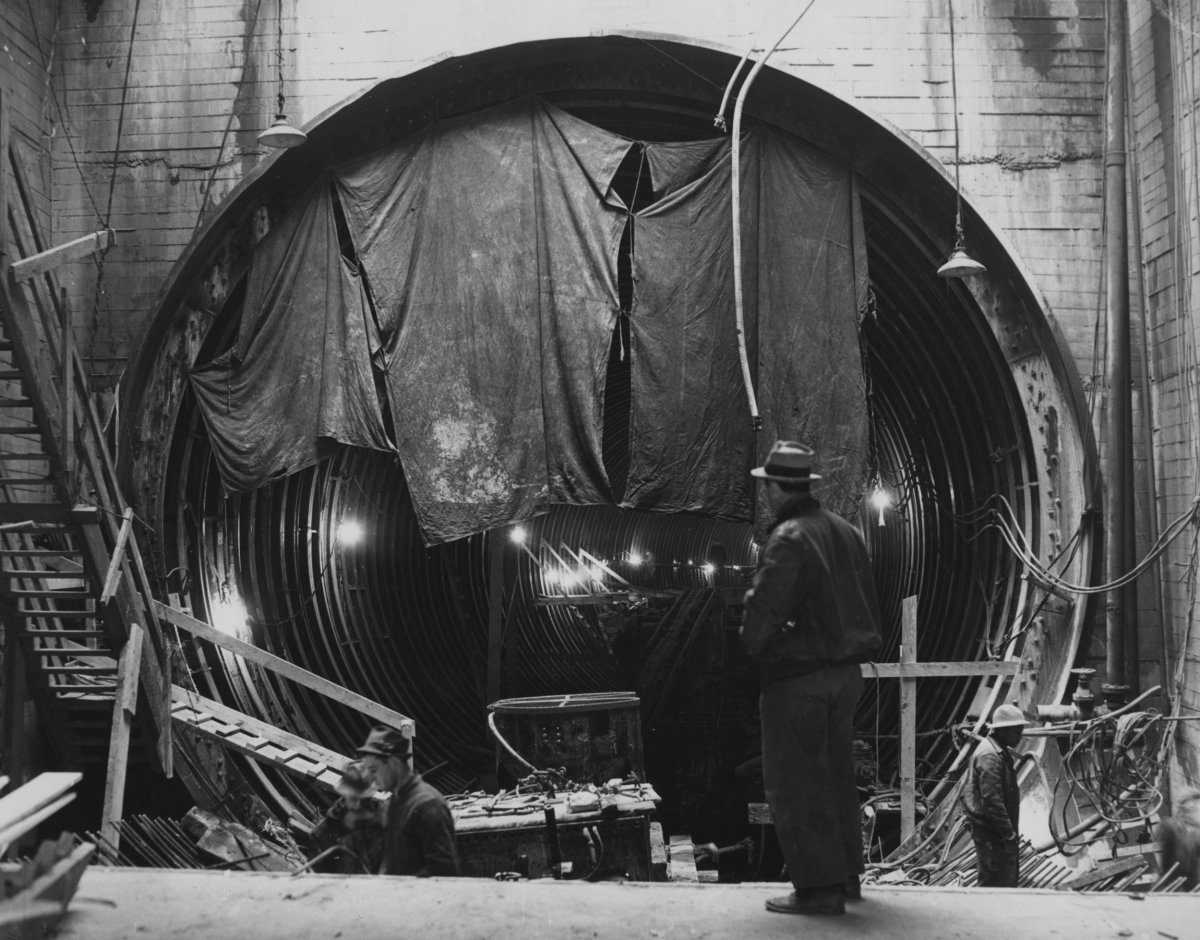

Construction on the Lincoln Tunnel began by blasting vertical shafts 80 feet deep into the bedrock on the west side of Manhattan. Workers got down the tunnel level via a slippery staircase. A 400-ton cutting shield was then constructed at the shaft's bottom, which would be used to burrow through the bedrock horizontally, driven by hydraulic jacks.

A July 1934 article in The New York Times inaugurated the next phase of construction, describing the placement of a 600-ton caisson—a watertight "bright red, hollow cube of steel" floated upriver from its New Jersey fabrication site and nudged into position with tugboats. The caisson acted as a prefabricated shaft, which could be extended down through river water, mud and muck until workers could reach the bedrock 20 feet beneath the riverbed and begin tunneling toward New Jersey.

Angus K. Gillespie's 2011 book Crossing Under the Hudson: The Story of the Holland Lincoln Tunnels described the grueling work sandhogs who went down into the pressurized shaft performed, working for $10 a day in two three-hour shifts, with a three-hour break in between. Tunnel diggers—including Irish, Italian, Black and Polish workers—blasted through and cleared between 25 and 35 feet of bedrock a day, assembling 21-ton iron rings (2,370 in total) to line the tunnel as they went. But just getting into and out of the tunnel was a tedious and dangerous process in itself, with an airlock used to incrementally adjust to the high pressure maintained to keep the shaft from collapsing.

"The turnover in workers was unbelievable," an anonymous sandhog tells Paul E. Delaney in Sandhogs: A History of the Tunnel Workers of New York, a short history provided in PDF form by Sandhogs Local 147, a laborers union headquartered in the Bronx. "Men would work an hour or maybe a shift, and they'd never be seen on the job again. Even the strongest men were tired after fifteen or twenty minutes in the air. And there was always the worry of being fired. If a man went for more than two sips of water during a shift, he was told to collect his wages and go home."

Tunnel workers were particularly susceptible to decompression sickness, more commonly as "the bends," which can create nitrogen bubbles capable of lodging in the body, sometimes causing paralysis if they work their way into the spinal column or brain. Known as "caisson disease" in the context of tunnel workers, the effects on workers were so dramatic that they sometimes collapsed on the streets or were arrested for seemingly drunk and disorderly behavior.

Such occurrences were common enough that after-work sandhogs wore metal badges, advising anyone who found them "stricken on the street" to rush them to an airlock on 38th street. "DO NOT send him to a hospital," the badge advises. But while decompression sickness killed dozens of sandhogs during earlier public works projects, shorter high-pressure shifts and closer monitoring mitigated the deadliest effects during the construction of the Lincoln Tunnel.

Still, the hard work sometimes led to deadly accidents, including three sandhogs killed in the first year of construction. Three more died in April 1935, when 133 pounds of dynamite were set off too close to five tunnel workers. A total of 15 workers died constructing the first two tunnels.

While no one died during the third tube's construction, the project wasn't without incident. In January, several months before its completion, the Hudson River poured in from the Manhattan side and three workers, the Associated Press described at the time, had to "swim for their lives."

Sandhog construction projects continue to be dangerous, with Local 174 workers—many second or third generation sandhogs—still at risk from deadly accidents.

New Yorkers and visitors can pay their respects at the Tunnel Workers Memorial, located at the northeast corner of Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. Adjacent to a bus turnoff, the memorial commemorates the 23 men who died between 1970 and 2000 building the City Water Tunnel No. 3, which will connect New York City to its upstate water supply via a 60 mile tunnel, supplementing the leaking and overtaxed water tunnels completed in 1917 and 1936. The memorial includes 23 manhole covers with the names of the dead and a flagpole with a base made of stone from the tunnel.

"The story of the Sandhogs is the story of New York," Sandhogs Local 147 says on their homepage. "The city above grew where the sandhogs ventured below. For generations we have risked our lives to make this great city work. Building tunnels is tough and dangerous work, so to protect ourselves we formed a union – Local 147 of the Laborers International Union of North America (LIUNA) and we strive to make our job as safe as it can be."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.