Searching For Superman—The Strange Disappearance Of Fritz Stammberger

He was an überman—born in war-torn Germany, handsome and charismatic, the first person to climb and ski an 8,000-meter peak without supplemental oxygen. But he also had a shadow side, one that involved betrayal, intrigue, maybe even manslaughter.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

This feature article was first published in the 2016 edition of Ascent and won that year’s Banff award for Best Mountaineering Article.

It snowed yesterday, breaking some branches on my aspens. My garden shears with the green handles hung where I had left them after last October’s pruning. I took them in my hand, knowing what was about to come. The reckoning began all over again. The mountain rose up. The climb resumed, my circular climb, toward a summit I can never reach, and Fritz will never quit.

Precious fragments, psychology calls them, those all consuming remembrances that leap from the most common things.

The French novelist Marcel Proust had his little cookies called madeleines. One dip into his tea, one taste, and suddenly he would plunge into the universe of his childhood.

Citizen Kane had his Rosebud sled. The smell of granite, the sound of chandelier ice, that menthol blue of crevasse walls. We all have memory fragments.

I didn’t go looking for those green-handled shears in order to remember. But I knew before grasping them that they would return me to Makalu via my friend’s garage one spring afternoon in 1978. That was when I was asked about going to Tirich Mir to identify the body of Fritz Stammberger who had vanished there in 1975.

I said yes without thinking. I’d never been to Pakistan, and didn’t know the way in, nor the mountain. Nor how I was supposed to find Fritz after the Canadians who’d spotted a naked body in the ice retreated in a storm before they could mark its location. I just wanted to go.

I tried to figure out what would need doing. I would take pictures, lots of pictures, and look for a diary or his odd round snow glasses.

Anything else? I asked my friend.

Yes, he said, fingerprints.

Of course. I would take an ink pad and some heavy paper.

No, said my friend. Fingers. We’ll need fingers. And his jaw.

This was in the days before body farms and TV forensics shows. It shocked me. “You mean break them off? And what, pull his jaw off?”

“We’ll get you some shears,” said my friend. “Like garden shears.”

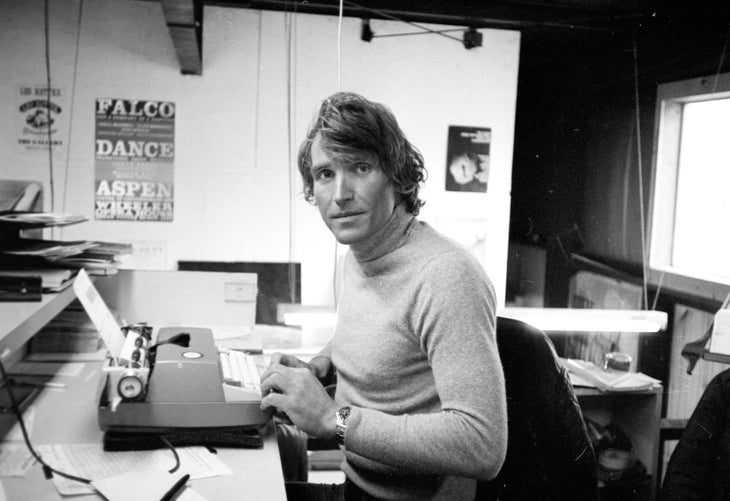

Fritz Stammberger (1940-1975)

“German expatriate, and resident of Aspen [Colorado] since 1963: Printer, extreme skier, Himalayan mountaineer, writer, filmmaker, publisher and local activist.”

A less formal obituary might have included: Beefcake, lone wolf, Himalayan bad boy, kamikaze, pioneer, showboat, visionary, CIA/KGB double agent …

Few climbers have ever heard of Fritz. Fewer still can name his accomplishments or controversies. And yet Fritz played a significant role in American mountain culture.

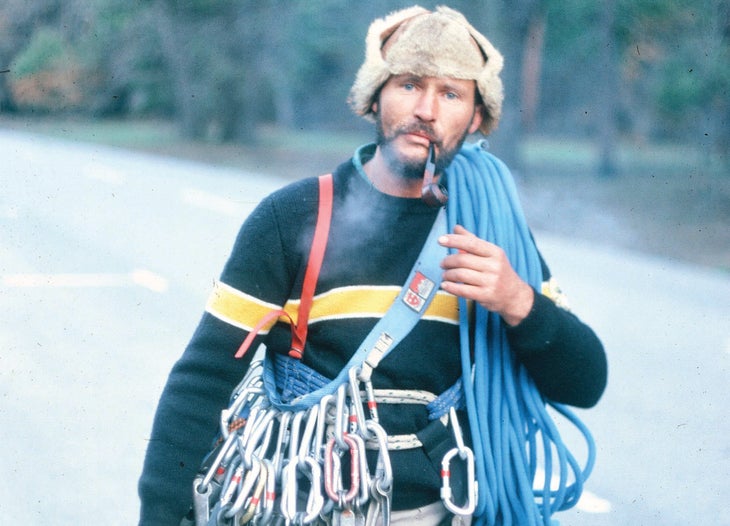

Back when American climbing was focused on the first free ascent of the Naked Edge and the right or wrong of Warren Harding’s bolt-bloat on the Dawn Wall, Fritz had his eyes on the Himalayas. It was an era when Himalayan mountaineering was a marathon race between nations (one mostly unattended by Americans), when the only question about siege tactics was how huge was huge enough, when Sherpas were nameless cannon fodder, and oxygen systems were essential weapons. Conversely, Fritz talked about international unity in the mountains, streamlined alpine-style climbs that did not rely on Sherpa muscle, and high-altitude soloing. In 1964 he became the first person to ascend without bottled oxygen and to ski-descend an 8,000-meter peak (Cho Oyu). He was the first to ski the “Deadly Bells” including North Maroon Peak (14,019 feet) near Aspen. And in addition to his climbing/skiing chops he printed Climbing magazine almost from its inception.

He truly was a superman, the übermensch of Nietzsche, an evolved being who dwelled on mountaintops separate from the herd below. Think of Batman brooding on a spire above Gotham.

The difference between Batman and Fritz was his conviction that Everyman could become Superman. He knew how powerful he was, but also believed we all harbor that power, the power of will and the will to power. If he could do it, he believed, anyone could do it. He was the ultimate equal-opportunity mountaineer, elite but not elitist. He wanted the so-called herd to escape from the valley and join him on the climb.

I know because, for a short while on a big mountain decades ago, I climbed with him.

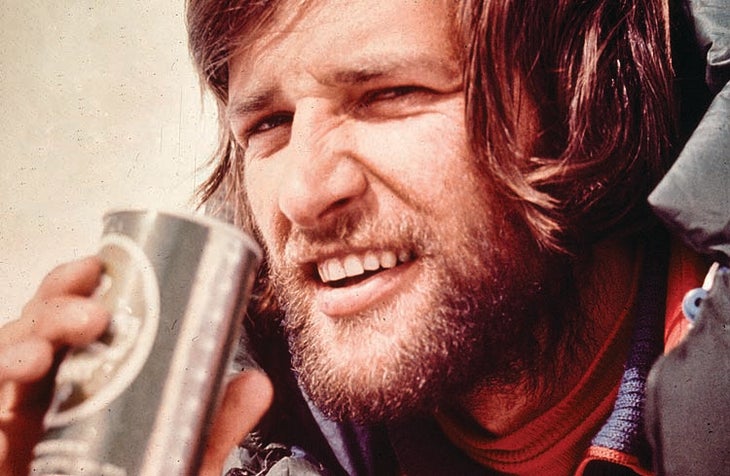

It was Fritz who introduced me to Makalu’s South Face in 1974. Charismatic, handsome and immensely powerful, he was a wild horse and the world was open range. I wanted to be like that, I tried to be, but it nearly killed me, just as it had killed other men, and just as it finally killed Fritz himself. Superman may be super, but he’s still a man.

Big calves, big heart, big dreams: multi-lingual, brimming with stories: Fritz was unlike anyone I had ever met. He had a boyish esprit, a vocabulary filled with English polysyllables that you had to practice to pronounce, and dressed in what was once described as “Teutonic Mod, with bold colors in tight wear from Sporthaus Schuster.” His were the sort of Hollywood good looks that can relax you at a party, because while he was in the room you were never going to get a date anyway.

Three months before the expedition’s departure, he married Janice Pennington, a former Playmate of the Year and a model on the game show The Price is Right.

Tall, honey-haired and California-regal, Janice had a magical naiveté. In a scene straight out of a fairytale, she had been literally swept away by this mountain man who worked as a printer in Aspen. On their second date, when she could not decide on the right shoes for the ballet, he insisted she go barefoot and carried her to the car. Beauty and the Beast: no casting company could have conjured such a coming together and had a movie audience believe it. They were made for each other. After Fritz went missing, Janice would nearly destroy herself searching for him.

It all started with the oddest want ad. Fritz’s 1974 expedition to Makalu needed a volunteer to help pack for a Himalayan expedition.

From the get-go the expedition had no room for me. I had no name, no resume and the prime age for Himalayan mountaineering was 35. That meant I had another 13 years of paying dues to go. Meanwhile, I reasoned, I could learn some more of the ropes by packing ropes.

On August 9, 1974, Richard Nixon resigned. That was also the day one of the climbers slated for Makalu broke his ankle. Two weeks before the expedition’s departure, Fritz asked if I wanted to go see a mountain.

After a Denver Post sendoff, we were floating on air. I’d been to Nepal once, alone, when I was 19, but this was different. The stewardesses served us wine. For free. And they were pretty. I was a man among men now, and we were famous. And we had Fritz. A lot of guys flex muscle. With all his muscle, Fritz didn’t need to. He flexed high spirits. He was a legend. He was our leader. He was a clown.

We could guess the cities passing below by his pantomimes: a cabbie for New York, a can-can dancer for Paris, and for Munich a drunken Bavarian who, inexplicably, looked up at a falling bomb. Fritz didn’t hold back on the bomb sound. I didn’t get the joke. Did it have to do with the terrorists at the ’72 Olympics? But Fritz’s grim grin immediately reverted to sunshine. I filed the odd moment under “silly.” We were man-children, after all. The Himalayas were our business, battlefield and playground.

In the dead of night we stopped to refuel in Teheran. No-bullshit armed soldiers gestured the passengers into the transit lounge and then back onto the plane. This was the Shah’s Iran, tightly controlled. As we crossed the tarmac between a phalanx of M-16s, Fritz suddenly became a human machine gun. Breaking our subdued file, he pivoted and started ack-acking at the soldiers. The passengers, including us, shied away, leaving Fritz in his own no-man’s land.

An officer approached. But first one of the climbers unfroze and gave Fritz a big push. He staggered. The climber smiled at the officer. Fritz was drunk, obviously, yes? We boarded. The remainder of our flight was subdued.

We clustered around Fritz and Rodney Korich, our base camp manager with the cowboy hat and shady shades, as they craned over an airline ticket counter in India. By sleight of hand, with an endless supply of Marlboros and an instinct for “tipping,” Rodney had so far saved the expedition $9,000 in baggage fees. His skills were no match for a fastidious bureaucrat with integrity, however. The man in front of us had rubber-stamp ink on his fingers. He didn’t want a pack of American cigarettes. He refused a bribe. He didn’t care if the phony paperwork said our cargo was checked through to Kathmandu. Unless we paid thousands of dollars in baggage fees based on the actual weight, we weren’t leaving.

Every bag needed to be reweighed. We knew the expedition was thin on cash, but were just now learning Fritz’s definition of thin: not fat free. Bare bone. The airfreight was about to bankrupt us.

But a miracle was unfolding. Somehow three tons of gear shrank to less than 600 pounds, or around $300. It didn’t seem possible. Then I stepped back from our little crowd and saw the toe of Fritz’s shoe wedged underneath the scale. And he still complained about being overcharged. I was learning.

We boarded our Royal Nepal Airlines plane. Last on was a skeletal hippie. Once in flight he started shouting about fucking, stinking Asia and other matters. He wouldn’t shut up, and I even thought about trying to subdue him with a Taekwondo joint lock. By the time we landed, people were ready to hang him.

While we waited at customs, Fritz surprised me. “He can’t help himself,” he told us in his accented English. “He chust flew too close to the sun.”

Somebody said, “You got to be kidding, the guy’s out of his mind.”

“No, no, he was sent for us to learn from him,” said Fritz. “He’s a messenger. Now we know, we must be careful as we go higher.”

Too eager, we arrived in Kathmandu at least a fortnight too soon. The monsoon was still on. That meant a drenched, 15-day approach march through a gauntlet we called Leech City. Fritz didn’t mind the leeches, though. Now and then he would pull one off and roll it in his fingers like a booger to flick away. “They are only doing what they were born to do. Like us going to Makalu. We were born to climb it, yeah?” He stretched a leech between his fingers. “The brotherhood of the rope.”

Every evening the Sherpas would serve our dinner on big tin plates. We each kept our own spoon and fork to ensure they were clean, or at least only infected with our own germs. Fritz would open his napkin and arrange his real silver silverware. Next would come his silver chalice. It looked like something from a church, a wine cup for holy communion, or treasure looted from a sea wreck. It was almost too literally a grail.

Everywhere he went, that chalice did, too, even at the high camps on Makalu. Like an Iron-Age chieftain, he drank everything from it, Lipton’s tea, Sherpa tea, chai, raw chang, rakshi, Johnny Walker Red, even Kool-Aid when it showed up in a packet of food. It was done without fanfare, but people rolled their eyes. I waited until much later when we were in private to ask about it. “Something from home,” was all he said.

A mutiny was brewing

Fritz was too intense. He was too strong. He did calisthenics at the end of each day. He was destroying us before we even reached the mountain.

“How can you trust him?” someone asked.

“He’s a threat to all of us,” said another.

“No one will climb with him in Aspen is what I hear.”

“They’re afraid of him. He wears a pack frame with weight plates to train on Capitol Peak. He never wears a parka or gloves when he skis. He carries snowballs around town in his bare hands. Cold showers, the whole bit.”

“He duct tapes his mouth shut to run up mountains. Or he goes with a mouthful of water, bottom to top.”

“A fanatic. He expects us to be like him.”

“These loads are killing us.”

They delegated Rodney to talk with Fritz. “You need to carry less weight, and walk slower,” he said. “You’re our leader.”

“No one is telling them what to carry. They should only take what they want,” said Fritz.

Next morning, Fritz strapped on his usual 70-pound pack. By way of counter-example, Rodney quit carrying a pack altogether. Ninety-nine-pound weakling or He-man: people resented the absurdity.

Makalu Base Camp. We sat in the lantern light with the wind bucking rime from the walls. The Europeans were talking about the war. Andre Ulrych owned Andre’s, a haute-cuisine restaurant in Aspen. Born in Poland, but like Fritz a transplant, he was along strictly for the view. As a child, Andre had survived five years in a Hungarian labor camp. Arnold Larcher and his friends used to play in a meadow littered with battle debris. One day a hand grenade severed a boy’s arm.

I kept a humble silence. My only war stories were about a scary pitch or a fall. Inflicting risks upon yourself is different from having them inflicted.

“I was a wild boy in the ruins of Munich,” Fritz said. “There was no one to tell us how to be. No one guided us or gave philosophy. Our fathers were in the army or dead.”

Arnold nodded in his cloud of pipe smoke.

“And Munich … ” Fritz shrugged. “A ghost. Every day more disappeared. The British bombed at night and the Americans in the daytime. It was the last year of the war. I was 5 and in kindergarten and had a fistfight, so I was late going home, just by a few minutes. The trains were already destroyed and the tracks were twisted. I was at the crossing when the air-raid sirens came on. I saw the plane. I think I did. It was big and silver and coming right down the street. I saw the bomb, too. Or maybe not.

“There was only a hole where the front of my house had been. The air was hot from the bomb. The bricks and pipes and metal, too. Every house along the street was gone. The street was gone. There was no one to tell me don’t go in there. The wood floor was on fire. The wallpaper had blisters. I pulled away some things. But you know, a 5-year-old, not very big.”

He shrugged and quit talking. No one asked questions. When we left for our tents, no one said good night.

It was our first day on the mountain itself, and progress was slow across the hot glacier. It’s true about climbers getting sunburned on the insides of their open mouths. We dropped our packs and took a break.

Fritz pointed his axe at me. “Little Fritz,” he said, his voice rusty with bronchitis.

I didn’t know what to do with that: Little Fritz? It was a joke, of course, it had to be. But Fritz wasn’t smiling.

I glanced around to see if the others had heard it, and they were looking right at me, as if waiting for the punch line. Maybe I was the punch line. What had he just laid on me?

He stood up, and his shadow fell directly on me, an instant oasis. The air cooled slightly. I could un-squint my eyes. Trees, that’s what this place needed.

Everyone else stayed lounging against their packs.

Fritz reached inside his pocket. Something silver flashed. With the sun directly behind him I couldn’t see his face.

Suddenly a whistle blasted.

I jerked. Fritz was looking at me. So were the others.

Was this the joke? Was Little Fritz Big Fritz’s poodle?

I couldn’t decide what to do. Was this a defining moment? Should I make a stand—by sitting—for my personhood, like in The Elephant Man? “I am a man.” Or roll with it, whatever it was.

The expedition—or my part of it anyway—was too young to have to wrestle with the meaning and its implications. And the afternoon was too hot to second guess.

I climbed to my feet. Fritz led off. For as long as I could, I followed.

Fritz and I came down from a carry. Our doctor had just carried up a load.

While we were eating he noticed some quirk in my respiration. “How long has that been going on?” he asked.

Fritz paused over his plate of food, listening. He had already warned me about modern medicine. The greatest conspiracy in history. He claimed a single aspirin would make him high.

But it was not bravado when I answered everything was fine. I honestly didn’t know what the doctor was talking about. We were all short-winded up here. Taking a drink of water had turned into baby sips between breaths.

Fritz and I would be carrying another load up in the morning. The doctor had intended to go back down. But he stayed in camp and shared a tent with me. Sleep was getting tougher. I would wake with a big gasp, sometimes sitting up.

The doctor turned on his light. “I can hear it from here,” he said.

That scared me. I couldn’t hear anything, and didn’t want to.

He gave me his stethoscope and held the drum just below my throat. It sounded like a worn-out knee in there, lots of popcorn.

“That’s rales,” he told me.

All right, I had bronchitis. So did others.

“Do you have a headache?” he asked. I said no. “That’s good,” he said. “But your lungs are filling with fluid. You have pulmonary edema. We’re going down in the morning.”

I was stunned. My climb couldn’t be over.

At daybreak the doctor informed Fritz. Fritz gave him a look. He didn’t come over and shake my hand. He just hitched into his pack and headed up.

I hung my head.

“You would have died,” the doctor told me.

I thought he was exaggerating.

You don’t go to the far side of the moon to dally in the sick bay. After a few days at Base Camp, I gave myself a clean bill of health, and returned to the face. With time everybody got sick. Everybody got hit by falling ice. Everybody began hallucinating.

My first day back on the conveyor belt, I looked up just as Arnold opened the butt flap on his wind suit. I was carrying a full pack and there was nowhere to move as brown paste splashed down.

It put to mind those Crusaders, thin as sticks and lit with Christ, riding through the white heat in armor leaking diarrhea.

Fritz drove his body like a farm animal. I woke to Arnold talking to his feet in German. I saw orange avalanches and elusive small Neanderthals.

The sun was bright, perfect visibility, no wind. Naturally it turned the snow to mush, and the nearly vertical trail refused to hold its shape. Again and again the steps collapsed and left climbers dangling from the fixed ropes.

The entire South Face above 21,000 feet was pitched at a 45- to 75-degree angle, and didn’t hold a single ledge to more than balance on with one foot or the other. Fritz had ordered our Slovenian-made reindeer-skin boots because no one had suffered frostbite on Matija’s 1972 Yugoslav expedition that had come within 500 meters of success. But the boots’ flexible soles were no good for the steep work; imagine strapping crampons onto mukluks. Every 15 minutes the boots spat off one or the other crampon, leaving me a choice: stop and restrap it on, or leave it off and paw at the ice.

News arrived from the Khumbu valley of a Yeti killing a yak and tearing a Sherpani to pieces. The non-climbers in Base Camp scoffed. Up on the hill, though, we added one more menace to the menagerie.

Fritz and I sat on a sleeping pad with our feet hanging over the Golden Porch. Our piss bottles had turned the snow ledge to rich yellow ice. A mile below, the glacier lay in shadow. It was a fine end to a fine day.

We passed the pot of lukewarm stroganoff back and forth. Beethoven’s “Eroica” dipped and swelled from Fritz’s tape machine. You could hear the Om in it filling the emptiness. We talked about mountains. Fritz saw Makalu as a perfect mountain, separate and geometrically true, its four sides forming a pyramid.

He said the first thing we should do back home was climb the Diamond on Longs Peak while our bodies were still acclimated. He talked about the need to do Everest without bottled oxygen. “Using oxygen in the mountains is like Mark Spitz using fins.” Did he think it could be done? He put one finger on his forehead and said, “Impossible is only here.”

“Evel Knievel,” I said. It was shorthand.

“Yes, exactly,” Fritz said.

The motorcycle jumper had come to occupy a special place on our expedition. Dressed like Elvis Presley, he was the epitome of American kitsch. He was going to try a jump over the Snake River in late September, and now it was October. Waiting for news of the jump had become a joke about our growing stupidity. At the same time, Knievel would have fit right in on the mountain. Peel away his red, white and blue spangles and fringe, and he was no different than we were, risking everything to soar above an abyss of our own making.

Camp Four

The sun was setting. We crawled into the tent and lay on our backs, head to toe. “What brought you to the climbing?” Fritz asked us. Arnold said something. I said something. Then it was his turn.

For some reason, he began talking about how they would surface into smoke and dust after the bombing raids. You could hear victims screaming under the wreckage, and smell the meat burning. At first he and his sisters had been intrigued by the brown statues lying on the street.

Then the bomb hit his house. Once again he described the wallpaper blistering and the walls still toppling. He had dug into the rubble. A few minutes before, an entire neighborhood had stood here. People were burrowing to find their own. No one had time for a 5-year old kid. No one told him to leave. No one helped.

He found a body. It was buried deeper. He quit digging and ran. “I don’t know where,” he said. “Somebody found me. They took me to my grandmother.”

That winter was brutally cold. There was no glass in the windows because of all the bombs. Many people lived like rats in the ruins. His grandmother sent him to forage for firewood in the wreakage of a cathedral. Its wooden pews were long gone, but he had spied a forest hanging above anyone’s reach.

The old churches had organ pipes made of wood. Scrambling above the wreckage of ivory keys and snapped levers, he wormed his way up and dislodged one of the pipes. He pulled it home on a sled. His grandmother sent him back to the cathedral over the coming months.

“In the cathedral,” he finished, “there is where I learned to climb.”

“And where you got your chalice,” I said.

He paused. “From the cathedral,” he said, as if it were just then occurring to him. “That would make sense, wouldn’t it.”

Our highest rope at 26,700 feet was just six ropes short of the French West Ridge. Connect to the Ridge and we would at least finish the jigsaw puzzle. To do that Fritz and Matija Malezic needed a third climber to swing leads and carry.

My HAPE had come roaring back, all but blinding me with retinal hemorrhages. Arnold’s toes were frostbitten. That left David Jones, an excellent mountaineer, who was strong and in good health, but afflicted with chronic misanthropy. “Life is a farce,” was his motto. Crabby as he was, Jones was one of those invisible super-mountaineers, like Charlie Fowler, who kept his myriad first ascents a secret. When he climbed, he was a force of nature. But he only climbed when the mood was right, and he didn’t like Fritz. Or any of the rest of us.

For the first week or more, while the rest of us had been setting camps, Jones stayed at Base Camp and ran wind sprints. Now he was up to bat. Forget it, he said. And out came his spew of catcalls behind Fritz’s back. He no longer used Fritz’s name, but rather “the Fanatic.” He dialed it up. The summit bid was insanity. Fritz was a kamikaze.

“I’m not going to be manipulated by anybody,” he warned us. “If they’re going to play games, then I’ll play games. I’m not going to be manipulated by anybody.”

Fritz and Matija decided to go for the summit without him.

Before starting up they locked hands and spat in mock team spirit. Their blitzkrieg, as they called it, came to a dead end at Camp III.

Through the telescope down at Base, I saw the tattered fly shuddering in a hurricane gale. Suicide.

That night, Base Camp radioed them to announce that we had taken a vote. If they wanted to commit suicide, we had no obligation to watch. If they ran into trouble, we could not rescue them. In fact, unless they gave it up now, they would descend to an empty Base Camp. The porters had been summoned. They would be arriving in two days. Base Camp was about to vanish.

The radio call shocked me. What vote? And who had said anything about ditching our summit climbers?

Through the telescope next morning I saw a tiny bulb emerge from the beaten tent. It disappeared back into the tent.

Hours later someone shouted. Two figures were descending.

On that first night of our surrender, we sat in a circle on the frozen turf at Base Camp. The bottle of Johnny Walker Red from Bombay was soon emptied. Fritz refused to say a word. He just slammed the bottle top down into the earth. People crouched or clutched their knees. They were afraid. It felt like a terrible storm was about to break upon us.

Jones emerged from the darkness and stood in front of Fritz. He launched into a bizarre tirade about the Fatherland, the Fuhrer, weak souls, ashes, Nazi evil.

“I just want that to be on the record,” he finished. Then he swept back into the night.

“And the son of a bitch is sober,” somebody said after he left.

Fritz took the tirade in silence.

We crossed Shipton Pass and descended to Sedua. The poorest of villages, it clung to the hillside like a Dr. Seuss hamlet. People wore burlap leftovers.

Our whiskey was gone, but now we had rakshi.

Night came and the moonshine kicked in. Somebody put the Stones on. The fire threw violent shadows. Arnold stomped around like a berserker. Fritz watched with a dazed smile.

I found Matija lighting a candle up on the pasture. He made a socket in the turf with his thumb, and shielded it with three stones. “A habit of mine,” he said. “I do so every year. All Dead.”

It was Halloween.

Next day we ran into the mail runner coming in.

Evel Knievel had failed to jump the Snake River.

The day before we caught our flights home, Fritz took Rodney and me with him to the ministry to obtain a permit for Makalu the next spring. It had to be the spring, because the Yugoslavs were coming in post-monsoon. The official said our permit was not possible.

“But we have left all of our possessions at Makalu,” Fritz explained.

The official consulted his file. He was sorry. The next available slot was 1977.

Fritz said that was too late.

The official did his little sideways bobble head. Maybe yes, maybe no: it was up to us to help find a solution.

We went into the hallway. “How much money do we have left?” Fritz asked Rodney.

“Not enough,” said Rodney.

Fritz turned to me. “How much do you have?”

I was down to $13. I had just spent $40 on a knife and some prayer flags. “Maybe I can get a refund.”

“How about Matija and Arnold?” Rodney said.

We had a grand total of $200. It would have taken 10 times that to wheedle the 1975 permit out of the ministry official. We returned to his office.

“1977,” Fritz told the official.

Ehrwald, Austria, 1975. Arnold’s house had burned down. I flew over to help him build a new one. We worked and climbed and talked about the upcoming 1977 Makalu expedition. In mid-October Fritz’s father called from Munich. Arnold listened and hung up.

“Fritz is in the Hindu Kush,” he said. “His father wants to know, have we heard from him. I said we didn’t even know he went.”

Arnold brought out a stack of old maps and magazines from his big cedar trunk. We located Tirich Mir. Fritz had gone over in September, alone. Janice had not heard from him for a few weeks.

We made sense of it with what we knew.

Fritz had tried Tirich Mir several times, starting with a solo attempt in 1961. That was when an American team mistook him for a Yeti after an avalanche nearly killed him. Another solo attempt, in 1965, failed, as did a team effort in 1973. Another shot seemed in order.

The timing made sense, too. He had suggested sneaking a re-do on the South Face before the Yugoslavs returned. When a journalist asked what was so urgent about Makalu, Fritz answered, “I left a suitcase over there.”

Spring had come and gone. Fritz sensed, as we did, that the Yugoslavs would complete the South Face route. So much had depended on a Makalu victory in 1974. Next up, he had meant to make a solo traverse of Antarctica, and then a ski descent of Denali, in winter, no less, and then a solo of Everest without bottled oxygen.

Makalu meant more than a buggered tick list. Fritz had believed we shared his belief in the transcendence of ascent. For him, growing up an orphan in the ruins (his father in the army), trust in other people did not come naturally. He had tried the team approach on Cho Oyu, and then on Makalu with us, and the results had been devastating. Makalu had triggered a crisis of faith.

Tirich Mir, then, was not just a mountain. It was a prayer.

Arnold and I agreed that Fritz would come walking down the trail anytime now. He was changing his oil, that was all, purging the old Makalu to prepare for the new one.

Around the same time Fritz disappeared, the Yugoslavs completed the first ascent of Makalu’s South Face. Fritz was probably dead by then. Less than a year later, Arnold would be, too, struck by lightning.

During my visit, it rained on Sunday, our climbing day. Arnold and I went to the bar, and he laid a copy of Alpinismus on the table. “Homework,” he said.

It was dated 1965. “Cho Oyu,” said Arnold. “The beginning of Fritz, the end of Fritz.”

Paragraph by paragraph, we revisited what amounted to the trial and condemnation of our friend. In April 1964, a small German expedition arrived at Cho Oyu (26,750 feet.) At 23, Fritz was the youngest member, and also, overwhelmingly, the strongest. In the space of 11 days he, two companions, and a Sherpa established a high camp (Camp IV) at 23,600 feet and immediately prepared for a summit bid.

Next morning, Fritz’s companions could barely get out of their tent, both stricken with HAPE. Fritz carried on to the top, becoming the first person to climb an 8,000-meter peak without supplemental oxygen.

Details vary about what happened next, but the outcome was the same. Back at Camp IV, Fritz strapped on a pair of skis and made the highest ski descent in history, bagging two world records in a day. His two partners died before they could be rescued.

That same November, Fritz delivered a presentation about the expedition to the American Alpine Club.

Four months later, in 1965, Alpinismus essentially accused Fritz of manslaughter for abandoning his companions in order to claim two records. Furthermore, Fritz’s claim of summiting was challenged based on the photos he brought down.

Based on the Alpinismus article, the AAC journal promptly denounced Fritz. “Although this does not disprove his ascent, it casts serious doubts on his veracity.”

Fritz went into self-exile in Aspen.

Badrighot Prison, 1977. After Fritz disappeared on Tirich Mir in Pakistan, I resurrected his 1977 Makalu permit and patched together an expedition to the West Face. I sucked as a leader, and sucked worse as a judge of people, or at least of one man, a mystery climber who disappeared after the first week. After our failed climb, I agreed to pick up Mr. Mystery’s trekking gear at the airport in Kathmandu. While we were climbing, it turned out, he had been muling black money and contraband for the Indian mafia. Customs was waiting for some idiot to claim his baggage, plastic barrels filled with 8,000 high-quality watch movements worth more than their weight in gold. When the customs agents removed one of the barrel lids the watch parts erupted. Thinking they were chocolate coins wrapped in foil, I broke into laughter. Then they shackled me with iron chains and took me to prison.

One afternoon a fellow prisoner—a Hindi entrepreneur from Patan—invited me to tea. What was left of the windowsills bore beautiful wooden carvings. Their paint had long ago peeled away and the gods and goddesses were melting away.

While Mr. Patan’s boy servant cooked ginger and milk chai over a fire on the dirt floor, we played a game of chess. At last Mr. Patan got around to his proposition. He had come to understand that I might know a certain mountaineer who had stored some belongings at a friend’s house. They were mine for the taking, but first I would need to take care of the rental fee.

Mr. Patan didn’t know the man’s name, but he had arranged to have a portion of the cache brought for my inspection. My curiosity grew. We walked to the front gate where Mr. Patan’s friend was waiting. He opened a rice sack, unrolled a prayer scarf, and drew out Fritz’s silver chalice.

I was speechless. Two years earlier, Arnold and I had decided that the silver chalice was long gone in Pakistan, that maybe it explained Fritz’s disappearance. Maybe he had drunk from it in front of the wrong people, and they had murdered him to get the chalice.

Here it was, though, on the far side of a net of chains and bars, a glittering, slightly dented holy grail. The man arranged a few other items on the ground: Fritz’s orange helmet, a blue ski sweater and a single jumar. There was even more in storage, Mr. Patan assured me.

Shaken, I retreated to my cell.

Fritz had found me. How the prisoners connected him with me, I couldn’t say. Once again I felt a responsibility to carry Fritz’s legend forward. “How much?” I had asked.

“What does it matter while you’re in here,” Mr. Patan answered. “When the time comes, we will find a reasonable price.”

My release came abruptly. The State Department stepped in on my behalf. I was given barely one minute to collect my possessions, and then ejected from the prison. Next morning I was to be deported from the kingdom and declared persona non grata.

It was 3:55 p.m. Against all advice, I returned to the jail and summoned Mr. Patan. How much? Two thousand dollars, he told me, a bargain.

Fifty dollars, I told him, take it or leave it. We settled on 67. He gave his friend’s address to my taxi driver, and I rode out into the countryside. Fritz had indeed left his suitcase in Nepal. Mildewed tents, salvaged rope, and rusty pitons lay piled in the corner of a hut. The prize was a locked duffel stenciled with “Makalu International – 74.” The sun was sinking. I slit the red cordura open with a knife.

Inside was a blue ski sweater and an orange climbing helmet. No journal, no maps, no clues. I rooted among worthless clothing and torn paperbacks. By handing the chalice to Fritz’s widow, I meant with one glorious relic to confirm the poetics of obsession.

But the thief was a thief. The grail was gone.

Los Angeles, 1988. Janice invited me for lunch. During the 12 years since Fritz went missing, she had become a beloved celebrity on The Price is Right. I expected a mansion, but found a modest ranch house.

She welcomed me, and as I stepped from the bright sunshine I did a double take at the man behind her. I almost said, “Fritz?” He was big and handsome.

Janice quickly introduced her friend, who I later learned was her fiancé, and possibly already her husband. Carlos de Abreu was polite, but with a bodyguard’s adhesive intensity. I had thought Janice wanted to chat about Fritz, but that seemed impossible with her lover present.

To the contrary, Fritz was lunch. Over iced tea and a sandwich, she made a proposal. It was time to tell the story of Fritz, the real story. Would I consider working on a book with her?

Fritz was still alive, she informed me. He was injured and lying on his side on a cold stone bench in a jail cell, probably in Afghanistan, or maybe Pakistan. A psychic had told her so. She spoke openly, with the long haul composure of a widow. Meanwhile Carlos was scrutinizing my reaction.

Janice went on. Hers had been a long, painful passage through heartbreak, duplicitous strangers and unusual allies. Among others, Elvis Presley had given her good counsel, and an ex-KGB agent had revealed how things work in the subterranean. It was quite byzantine, but reduced to this: Fritz was a spy. Tirich Mir had been an elaborate ruse. He had never gone to the mountain.

She had searched and grieved and come up with a tale that gave her solace. Plainly my role in this had little to do with writing. She—or Carlos—wanted someone from Fritz’s mountain world to sign off on a conspiracy theory that rejected the very essence of Fritz: Ascent.

I put a few questions, gently and respectfully. Yes, she answered, she was aware that Bil Dunaway and another friend had gone searching for Fritz, and had found some of his non-climbing possessions in the last village. She also knew that Fritz’s father had sent two German climbers to look for him, too. The fact that they had not found Fritz proved her theory. As for the possessions, anyone could have planted them.

Why, if he was so bent on going alone to fight in the Cold War, had Fritz asked a close friend in Aspen (Michael Ohnmann) to go with him to Tirich Mir, and when that failed had asked Janice, who had to work, and then flown to Germany to ask other climbers?

Did she know about the Canadians finding a body and clothing right where Fritz would have been climbing? The basic response: What body? Whatever they found could have belonged to another climber, or simply been a fiction in a cover story.

Last of all: Was she aware that people convinced the body was Fritz’s had almost sent me over for forensic identification? Janice sat back. She blinked.

Carlos spoke. He was quite diplomatic. Collaborations are difficult enough between willing partners. He did not have to state the obvious. I was neither willing nor a collaborator. Lunch was over.

Six years later Janice’s book about Fritz, Husband, Lover, Spy, was published. It was a cross between a romance novel, a who-done-it, and an espionage thriller. “He was everything she’d ever dreamed of,” the jacket copy read. “But he wasn’t the man she thought she knew.”

That last part seems to be true. Fritz was not the man any of us knew.

1978. A decade before I met with Janice, a decision had needed to be made. Was it worth sending me to Pakistan or not? Was I still up to the task? It felt like a betrayal if I said no. It was coming back to me, though. I had already done this. Less than a year before, I had gone into the underworld.

I held the shears and closed my eyes and sank again into Kathmandu.

They told me I was the only Westerner in all of Nepal’s jails, as if it were an honor. Once a day they let me exercise in the narrow corridor lined with cells. They kept the far end perpetually dark, like the basement you don’t want to go in. Whatever they kept caged back there hooted and barked and shrieked so much at night that I mistook it for the political prisoners being beaten and electric-shocked upstairs. What looked like dozens of butterflies clung to the outside of the far cell door.

I gradually extended my walks into the darkness, and finally realized the guards didn’t care. To that point, I felt a sort of repulsed curiosity. Then I looked inside and saw their animal.

There he stood waiting for me, naked and covered in brown war paint. The walls were painted with primitive bas-reliefs. He had plastered his rasta hair into ram’s horns. His teeth were caked. Dipped and tied to the iron bars and now dried stiff, the butterflies were strips of torn clothing.

Shit. It was, all of it, human shit.

They had barred his wooden shutters closed to prevent him from terrifying the street. His eyes were the only light in there, however bloodshot and starkly insane. He lunged at the door.

Next day I tried again.

I pieced the man together with bits of info pulled from the guards. What remained of his Dutch passport was expired. He had eaten the rest.

Hoping to halt his bowels, they only fed him every few days. He had been here for two months.

One day I washed him. The guards unlocked his door. I was still strong from the mountain, or at least not yet wasted by jail, and I knew tricks for subduing a person, which is not the same as a raving lunatic. It was like wrestling a large eel with teeth. I carried him, thrashing and howling down the stairs, to a water spigot in the center of a shaft that opened to the sky.

With the bucket the guards used to clean their asses after a dump, I poured water on him and wiped the dung from him. It went on for an hour. His hair—the horns—took longest. I washed him, I washed me, I washed him.

Resurrection, that was my hope, or conceit. Saving this poor fallen soul might not save my own, but at least I could congratulate myself for my humanity. His madness would lift. Not much, I wasn’t that foolish, but maybe enough to glimpse the edges of the world of the living again.

A ray of noon sun lanced down.

At the same time, it was raining. Drops pattered on my head and shoulders and dimpled the water on the floor. I lifted my head to it. Let the monsoon pour down.

But then I saw the guards and soldiers lining the walls at each level, and they were spitting on us.

A friend contacted the proper embassy. The madman was evacuated back to Europe. He had bitten me, and I was bruised for days, and physically sick for weeks. That was OK. I had saved a life. A real life.

I laid the garden shears down.

Fritz had chosen his mountain. It was time for me to let him have it.

The mountains are our underworld. If you doubt that, try the top of a Tibetan pass sometime. Lung ta—wind horses printed on slips of paper or cotton flags—gallop their prayers into eternity. Animal skulls, carved and painted, whistle into the void. Up there, every one of us is an exile only partway to somewhere, but with this difference between us: the living may not stay; the dead may not pass.

Up there, one bears witness to the other, the summit to the abyss, which is half empty to what is half full. In the end we are the measure of our desire. How full we fill the emptiness, that is our legend. Empty legends, that is the wind.

Jeff Long is the author of nine novels. His novel The Ascent was awarded the 1993 Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature.