Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The Curious Case of Maurice Wilson and his Doomed Quest for Mt. Everest

In 1933, two decades before Mt. Everest was first climbed (by a huge British-led expedition), Maurice Wilson, a 34-year-old Englishman, declared to the world that he would climb the peak—alone. Moreover, he would travel to its base by a solo flight from England. Before his death on Everest’s icy northern slopes in the summer of 1934, Wilson had become one of the most controversial figures in mountaineering history, alternatively revered and reviled by commentators in the press, public, government, and the mountaineering establishment.

Wilson’s body has continually resurfaced from its glacial tomb after successive burials by later expeditions—first in 1959, then in ’75, ’85, ’89, and again in ’99—but his story has largely faded and his legacy remains unclear. Was he a crazed mystic? A pioneer of light-and-fast alpine tactics? A naïve, wannabe mountaineer? In fact, none of these descriptions get to the heart of this most bizarre Everest hopeful.

Wilson was by any standards an unlikely candidate to be first on top of the world. A minor war hero, he had been shot twice during the ghastly trench warfare of the First World War, leaving his left arm permanently immobile. In the years before his climb, Wilson also suffered from a monstrous bout of tuberculosis and a nervous breakdown. Moreover, his ability to persevere seemed questionable at best; he had a penchant for aimless wandering—a post-war jaunt around the world left in its wake a slew of unfinished jobs and abandoned wives. But most damning, Wilson had never before flown a plane, nor had he ever climbed a mountain.

After two months of flying lessons at the London Aeroplane Club and with one fuselage-buckling crash behind him—as well as some hiking in the Lake District—Wilson took off on May 21, 1933. Unable to afford a state-of-the-art plane, he’d settled for a used 1925 Gypsy Moth. Far from the custom-made Spirit of St. Louis flown by his contemporary Charles Lindbergh, Wilson’s aptly named Ever-Wrest was an open-cabin biplane, more reminiscent of what the Wright brothers had used than the slick and sturdy Spitfires and Me 210s that characterized the decade. As Wilson set off across the English Channel, he left a flurry of front-page chatter behind him.

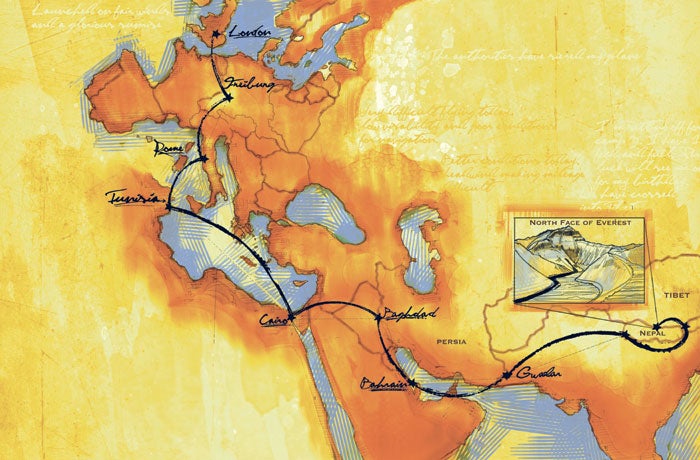

With a 620-some-mile fuel range and geography and weather to consider, Wilson’s route wove all over the map: London to Freiburg, Freiburg to Passau, then an aborted attempt to cross the Alps and a retreat back to Passau and Freiburg. Wilson finally flew over the Western Alps to Rome, where the news of his endeavor preceded his landing and a large and enthusiastic reception greeted him. A few days later, while flying across the Mediterranean toward Tunisia, Wilson—for the first time in his life—was forced to fly through complete cloud cover, a challenge the novice somehow managed to pull off. One week after leaving London, Wilson reached Cairo, and a few days after that Baghdad. The newspapers went wild.

Mountaineering stories were front-page news in the 1920s and ’30s, in an atmosphere akin to the space race decades later. And Wilson’s story was, of course, particularly newsworthy. Even the Times, the pillar of respectable London journalism, got wrapped up in the Wilson hype, though reporting in more reserved tones than its boulevard competitors. Between 1933 and 1934, the Times alone published 151 articles on Mt. Everest, nearly 100 of which mentioned Wilson’s quest.

Unfortunately for Wilson, neither the British government nor the mountaineering establishment was as enthusiastic about his endeavor as the public was. Though Everest remained unclimbed, this was not from lack of trying. In the 1920s and ’30s, numerous British expeditions had attempted to conquer the mountain, including the infamous 1924 expedition during which summit hopefuls George Mallory and Andrew Irwin disappeared. What all of these expeditions had in common—besides failure—was their large-scale, military character and their close supervision by the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographic Society. These elite, upper-class institutions, with tight links to government and the military, did not look kindly on foreign nations or non-members trying their hand at the “third pole.” (Mallory, no doubt the only socialist among this stuffy crowd, was simply too good of a climber to be ignored.) Though many Alpine Club members must have enjoyed mountaineering for its own sake, these expeditions were about much more: national glory.

Moreover, Wilson’s planned flying route would take him over Persian territory and ultimately into Nepal or Tibet. Previous expeditions had relied on high-level British diplomatic bullying to force these reluctant countries to cough up the necessary permits. In Wilson’s case, however, the British Indian government and the Air Ministry gave him only their stern assurances that they would offer absolutely no support. The implications of this dawned on Wilson only once in Baghdad. With no Persian permit forthcoming, he was forced to turn south along the Arabian Peninsula—an eventuality he had refused to consider and for which he had no maps. Unperturbed, he consulted a children’s atlas and then set off on the 620-mile stretch from Baghdad to the next airfield in Bahrain. Flying in scorching summer temperatures, he managed to land just before running out of petrol.

In Bahrain, for the first time, British officials actively intervened to prevent Wilson’s progress. A police officer invited Wilson into his office and informed him that the Royal Air Force had declared the air space ahead “closed to civilian air traffic”—Wilson was to turn back immediately to Baghdad or face arrest. Ever the optimist, Wilson used his interview as an opportunity to sneak a glance at a large map on the offi cer’s wall, jotting down some notes on his hand while the latter was distracted. Wilson immediately took off, feigning a flight back to Iraq, then turned his plane straight east toward British India. Midway along this 745-mile stretch—a distance theoretically beyond the capacity of his plane—the Ever-Wrest’s weary engine sputtered to a complete stall, and Wilson was forced to perform the complex emergency procedures he had no doubt practiced seldom, if at all, during his brief flight schooling. He landed safely in Gwadar just as the sun was setting. In this one-day marathon flying session, with his primitive airplane and neophyte skills, Wilson achieved a feat no less spectacular than… well, perhaps than climbing Mt. Everest.

From Gwadar, Wilson needed only a few days of leisurely flying to reach the last airfield in India before the Nepali border. As the press was quick to note, he had traveled some 4,350 miles in 17 days. Whatever joy Wilson might have taken from this accomplishment, however, was quickly dashed—the local British constable promptly impounded his plane. He was then placed under surveillance. But Wilson did not give up. With the monsoon in full swing, he traveled the 186 miles by road to the Nepalese border, where he tried in vain to make a direct phone call to the king. The Kathmandu bureaucrat on the other end of the line was unswayed by Wilson’s rhetoric. There would be no permit for flying into, hiking to, or climbing Mt. Everest from the Nepalese side.

Wilson sold his plane and moved on to Darjeeling, India, where he attempted to secure a permit to approach and climb the mountain from the Tibetan side. No luck. Undeterred, Wilson spent the fall and winter in Darjeeling training and scheming, all the while doing his best to convince the vigilant local authorities that he had abandoned his Everest plans. Early one morning in late March 1934, disguised as a Tibetan lama and accompanied by three Everestseasoned Bhutia porters, Wilson snuck out of town and set off through Sikkim toward Tibet. Traveling at night, the men reached the Tibetan border in a brisk 10 days. Other than an elderly man who, upon hearing that a lama was camped outside of his village, snuck into Wilson’s tent late one evening, the group managed to remain incognito. By mid-April, they reached the Rombuk Monastery, just below the traditional Everest basecamp.

With the same spirit he showed on his flight across the endless, scorching desert the previous summer, Wilson set off up the imposing Rombuk Glacier, hoping to tag Everest’s 8,848-meter (29,028-foot) summit on his birthday, April 21. He repeatedly lost his way on the giant glacier, but managed to climb to 6,000 meters. Somewhere in the vicinity of the previous expeditions’ Camp 3, around 6,500 meters, he turned back in a nasty snowstorm, retreating to his tent on the glacier for two days and nights. It was here, alone in his tent, that he celebrated his 36th birthday. That night, the storm let up and Wilson made a break for it, trudging through three feet of fresh snow for 16 hours before reaching the monastery.

Back at Rombuk, Wilson revised his plan and convinced two of his Bhutia guides to accompany him as high as Camp 3. On May 12, the group left the monastery and made quick progress up the mountain. They were able to locate the gear Wilson had left behind after his previous attempt, save the crampons he had previously scavenged from an abandoned cache and then tossed aside before retreating, which were nowhere to be found. After one failed attempt at reaching the North Col, Wilson set off alone again on May 29, asking his porters to stay at Camp 3 for 10 days—a request they very likely ignored. This was the last time anyone saw Maurice Wilson alive. The following year, Eric Shipton and Dr. Charles Warren found his remains, as well as his journal, in the vicinity of the British Camp 3.

It is unclear how high Wilson actually got before succumbing to his lonely death, some 2,300 meters below Everest’s peak. In all likelihood, he never reached the 7,010-meter-high North Col. While attempting to ascend the steep, icy slope above Camp 3 toward the North Col a few days earlier, Wilson and his experienced Bhutias had quickly been forced to turn around— Wilson, of course, had no crampons and was wholly unfamiliar with stepcutting technique. Alone, technically unskilled, with an immobile arm, but powerfully driven, Wilson most likely made his best attempt at the ice wall, gave it up, then returned to the vicinity of Camp 3 to find his porters missing. No explanation exists for why he was found, without his sleeping bag, a short distance away from Camp 3, with its copious food depots.

Though Wilson’s novice effort was remarkable, his highpoint was unspectacular when compared to his strongest contemporaries. Mallory had easily reached the North Col during the British 1921 reconnaissance expedition; the following year, George Finch had managed to climb to over 8,000 meters. Mallory and Irvine disappeared even higher on the peak in 1924—some believe they reached the top and fell while descending. In the years following Wilson’s attempt, however, it was less the details of his ascent than his nonconformist style that was celebrated, debated, and debased.

Rumors and speculation regarding Wilson’s motives and his character, ranging from ridiculous to irrelevant, abound to this day. A Wikipedia entry suggests he made the climb to promote a mystic, pseudo-Christian doctrine of fasting and prayer. Though Wilson did claim to have been cured of his tuberculosis by this prescription, and boasted to one reporter that this might be the ticket to tagging Everest, his conviction seems largely to have worn off by the time of his expedition. (In his diary, he readily admits to eating generous portions of just about anything he could get his hands on.) Another source claims Wilson was a cross-dresser who kept a secret sex diary—hardly relevant to his Everest bid. Both rumors are closely linked to the image of Wilson promoted by the mountaineering establishment: that he was a dilettante madman recklessly trying his hand at what was a real man’s game. Contemporary Alpine Club commentators spruced up their claim by exaggerating Wilson’s naïveté and inventing fictitious details.

Of course Wilson was a novice climber; of course he was unprepared for Everest—but he was not wholly ridiculous. His spectacular flight from England to India showed that he was not only extremely brave, but also capable of mastering complex skills in a short time. Moreover, during his months in Darjeeling, he sought expert advice from the many locals who had supported previous British expeditions, and went on numerous alpine hikes to practice and acclimatize. He procured as much specialty equipment as he could without support from the Alpine Club, including custom insulated boots and a state-of-the-art Meade high-altitude tent—stolen from a previous Everest expedition’s cache. Wilson’s plan to climb Everest alone was crazy, but was he any crazier than Mallory, Irvine, or the many summit hopefuls in more recent times who have been tragically reminded that safety in the high Himalaya is largely an illusion?

The damning image of Wilson was promoted for the simple reason that the Alpine Club, the Royal Geographic Society, and the British government insisted that the world’s highest peak could only—should only—be conquered by and for the nation. This belief grew directly from the climate of the time: the First World War had unequivocally destroyed illusions of national grandeur and infallibility in warfare. Instead, sports became the favored arena for competition between nations. (The idea that cheering for a soccer team could somehow be patriotic would have seemed absurd only 50 years earlier.) Mountaineering, a most symbolic sport, was hijacked by modern nationalism.

But the Great War had also unleashed a longing for individual redemption. Those veterans the war did not leave grotesquely disfigured, it scarred emotionally. The men of this “Lost Generation” found solace in the populist ideologies of the extreme right and left, or, as in the case of Wilson, in a search for the ultimate personal experience. Wilson was the first man to venture toward a Himalayan peak alone, without the financial support of a mountaineering association, without military logistical expertise, and, most significant, motivated by something less tangible, but infinitely more powerful, than raising a nation’s flag. The fact that he was able to fly from London to India, hike to Everest’s base, and mount an attempt at the peak—albeit one bound to fail—in spite of repeated attempts to trip him up, speaks to Wilson’s unwavering strength of mind. He had all the qualities—except mountaineering skills—that we would only two generations later uphold as the epitome of climbing virtues.

A few well-known climbers immediately recognized and admired Wilson’s spirit. After discovering Wilson’s body and diary, Eric Shipton told the police in Darjeeling that he had been deeply moved by Wilson’s conviction and elegance, his love of nature, and his belief that all diffi culties could be overcome by willpower—all very evident from reading through Wilson’s diary. And when Reinhold Messner camped at 8,000 meters during Everest’s first solo climb, he asked himself if he was as crazy as Wilson. This may be the ultimate lesson from Wilson’s experience: that the line separating a bold and exemplary quest—futile or not—from a misguided and crazy one, is as gray as the stormy sky.

Martin Gutmann teaches history and mountaineering and runs the outdoor program at the international boarding school Ecole d’Humanité in the Swiss Alps.