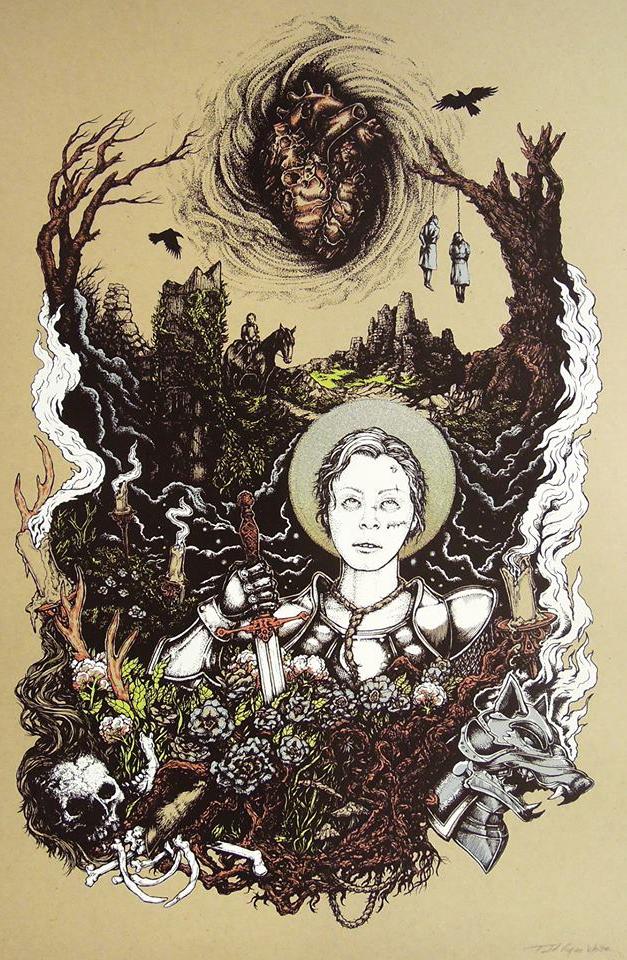

art by Malky Dungeon

There was no way out of the war. The land is a graveyard by the end of book three. The crops have been burned, the villages ravaged and abandoned, and the people strung up by one side for having the gall to survive under the other.

There was no way out of the war. Four of the five kings for whom it was named have been killed: one by his followers, another by his in-laws, and two by their own brothers. The fifth is destined to burn it all down around him, and knows it. In the final moments of book three, the most prominent character to die in the story so far is revealed to have been reborn, lacking in all humanity. The trees no longer bear fruit, but her nooses instead.

There is no way out of the war. The story that grew from an image to a letter to a book to five books to a successful show to a behemoth designed to turn a profit long after we’re all dead to now, in which the story is both done and not, an eternal implication, a breath held forever with a world in the balance…just for a moment, that story stops.

Silence reigns.

But even silence dies.

There are footsteps in the graveyard. Someone is stirring up the ash and dust. Someone is wilting every grieving flower as he passes. Someone is coming, and smiling, and singing.

“Crow’s Eye, you call me. Well, who has keener eyes than the crow? After every battle, the crows come in their hundreds and thousands to feast upon the slain. A crow can espy death from afar. And I say that all of Westeros is dying. Those who follow me shall feast until the end of their days.”

His rivals scowl and slink off to pool in the shadows of mildly more forgiving claimants to the protagonist’s throne. His followers flock around him, eyes shining with the reflected light of his promises. They add their voices to his, hoist him on their shoulders, over the horizon, banners in the wind, candles in the darkness, oozing and melting, the song cuts short and you look back and the altar is broken and the king is still smiling, but his eye isn’t. The graveyard moves behind that eye, and the dead crawl out of it chanting:

“The bleeding star bespoke the end. These are the last days, when the world shall be broken and remade. A new god shall be born from the graves and charnel pits.”

This is Euron Greyjoy, the way out of the war. His world was made to be ended by him, but as usual, he is late.

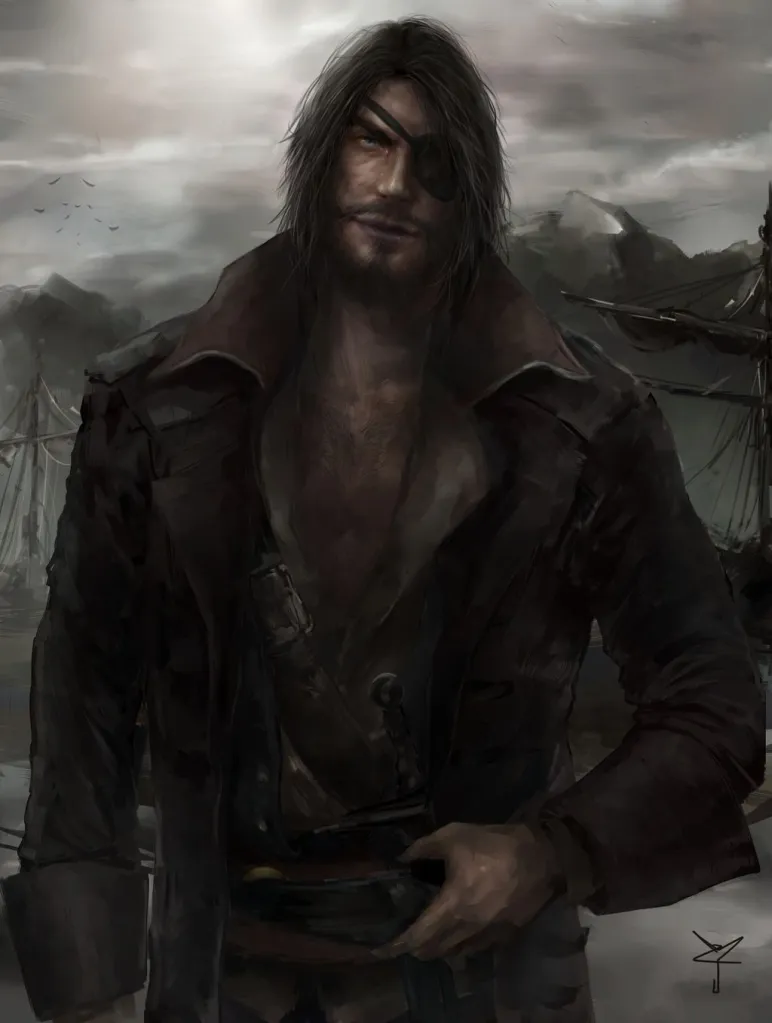

art by Nick Zero

The first member of the Greyjoy family we meet is a cocky young man named Theon, later referred to as Reek when all the cockiness is gone. He strides into book two confident that after the death of Ned Stark, his foster father/jailer and the focal point of book one, he is the protagonist now. “This is the season … the season, the year, the day, and I am the man.”

Only one person gives him pause.

Old men were cautious by nature. His father was old now, and so too his uncle Victarion, who commanded the Iron Fleet. His uncle Euron was a different song, to be sure, but the Silence did not seem to be in port.

“Euron Crowseye has no lack of cunning, though. I’ve heard men say terrible things of that one.”

Theon shifted his seat. “My uncle Euron has not been seen in the islands for close on two years. He may be dead.” If so, it might be for the best. Lord Balon’s eldest brother had never given up the Old Way, even for a day. His Silence, with its black sails and dark red hull, was infamous in every port from Ibben to Asshai, it was said.

These are the first mentions of Euron. Theon is clearly terrified of him. But why? He doesn’t seem to know, to remember. The truth awaits him on the other side, after his tormentor Ramsay has eaten through every door inside him. A termite set loose in a haunted house never knows what ghosts his gnawing might unleash.

Crowfood. Theon remembered. An old man, huge and powerful, with a ruddy face and a shaggy white beard. He had been seated on a garron, clad in the pelt of a gigantic snow bear, its head his hood. Under it he wore a stained white leather eye patch that reminded Theon of his uncle Euron. He’d wanted to rip it off Umber’s face, to make certain that underneath was only an empty socket, not a black eye shining with malice.

Theon saw the eye. A black hole drinking light. An egg in his mind, hatchlings whispering at night. You saw the Crow’s Eye. The truth is buried deep.

The truth is that Euron came back wrong. Not back from his mystical adventures in exile, though those certainly don’t seem to have helped. Back from inside. Theon refers to Euron as being a “different song” from the rest of the Greyjoys in the same breath he tells us that his uncle named his bloodred ship the Silence, all telling choices of words given the title of the story in question: A Song of Ice and Fire. Every faction, every character arc, every song in the story comes together in the overarching Song of Ice and Fire, and sailing in on the tide of blood and roses comes the Silence like a narrative emetic, a red egg with black inside.

A single-masted galley, lean and low, with a dark red hull. Her sails, now furled, were black as a starless sky. Even at anchor Silence looked both cruel and fast. On her prow was a black iron maiden with one arm outstretched. Her waist was slender, her breasts high and proud, her legs long and shapely. A windblown mane of black iron hair streamed from her head, and her eyes were mother-of-pearl, but she had no mouth.

Euron came back from inside with the end. He has come to silence the song and replace it with himself, invading not just Westeros but the story itself.

art by Jen Zee

Euron’s name is mentioned once more in the story prior to A Feast for Crows (the fourth book, named in his honor to coax him into finally appearing in the icy pale flesh). It comes in the context of Euron returning to his native Iron Islands from his years in exile, killing the brother who exiled him, and claiming his crown.

“My last port of call afore Seagard, that was Lordsport on Pyke. The ironmen kept me there more’n half a year, they did. King Balon’s command. Only, well, the long and the short of it is, he’s dead.”

“Balon Greyjoy?” Catelyn’s heart skipped a beat. “You are telling us that Balon Greyjoy is dead?”

The shabby little captain nodded. “You know how Pyke’s built on a headland, and part on rocks and islands off the shore, with bridges between? The way I heard it in Lordsport, there was a blow coming in from the west, rain and thunder, and old King Balon was crossing one of them bridges when the wind got hold of it and just tore the thing to pieces. He washed up two days later, all bloated and broken. Crabs ate his eyes, I hear.”

The Greatjon laughed. “King crabs, I hope, to sup upon such royal jelly, eh?”

“Aye, but that’s not all of it, no!” He leaned forward. “The brother’s back.”

“Victarion?” asked Galbart Glover, surprised.

“Euron. Crow’s Eye, they call him, as black a pirate as ever raised a sail. He’s been gone for years, but Lord Balon was no sooner cold than there he was, sailing into Lordsport in his Silence. Black sails and a red hull, and crewed by mutes. He’d been to Asshai and back, I heard. Wherever he was, though, he’s home now, and he marched right into Pyke and sat his arse in the Seastone Chair, and drowned Lord Botley in a cask of seawater when he objected. That was when I ran back to Myraham and slipped anchor, hoping I could get away whilst things were confused. And so I did, and here I am.”

“Captain,” said Robb when the man was done, “you have my thanks, and you will not go unrewarded. Lord Jason will take you back to your ship when we are done. Pray wait outside.”

“That I will, Your Grace. That I will.”

No sooner had he left the king’s pavilion than the Greatjon began to laugh, but Robb silenced him with a look. “Euron Greyjoy is no man’s notion of a king, if half of what Theon said of him was true.”

Euron does not come out of nowhere in book four, as is frequently argued. One of George R.R. Martin’s great skills as a writer is building up a character through their reputation, so that by the time they’re actually introduced, we have a strong sense of who they are and what they’re all about. We know before meeting Stannis Baratheon that he is tough as nails and has a sour temperament. We know before meeting Doran Martell that “he is a man who weighs the consequences of every word and every action.” And we know before meeting Euron Greyjoy that he is categorically different from the rest of his family, that he has a hideous reputation both at home and abroad, and that we’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg.

We never learn what Theon told Robb about Euron, any more than we learn the “terrible things” his sister Asha has heard about their uncle, because we don’t need to. The look with which Robb silences (there’s that word again) the Greatjon tells us all we need to know. Robb Stark has plunged headfirst into the horrors of the medieval battlefield, “men screaming like horses and horses screaming like men,” yet only now, standing on Death’s doorstep, does he feel its iron presence growing close. Euron brings it with him. Can you challenge the ferryman to a duel? How do you strategize to do battle with a darkness leering at you from between the stars…

But the Red Wedding awaits Robb, however much we might beg him to turn back this time, and I spoke of a crown.

art by Tommy Arnold

The most prominent ideology among the ruling caste of the Iron Islands is known as “the Old Way.” It tells the story of glory stolen from them by the mainlanders, who are properly sheep to be shorn by the Ironborn. The latter ought to be beholden to none but themselves, taking from the mainland whatever they will, property or person.

The Old Way is a human-pyramid pyre collapsing in on itself. It’s naught but atrocities built on self-flattering lies built on larger-scale atrocities, as ruinous to the long-term prospects of the Ironborn people as it is to the short-term prospects of the unfortunates in their path. A New Way can be found struggling alongside the old in the efforts of reformers like Lord Quellon Greyjoy, but their work is always swiftly undone by reactionaries…like Quellon’s son and heir, King Balon Greyjoy.

Balon’s all-consuming belief in the Old Way is the foundation of his character. He takes control of the Iron Islands after his father dies during Robert’s Rebellion, in which the Baratheons replace the Targaryens as the continent’s ruling dynasty. Lord Balon assumes that the fledgling regime will prove weak, leaving the window open for the Iron Islands to regain their independence and resume the Old Way. As always, Balon turns out to be completely wrong. King Robert calls the banners in response to Greyjoy’s Rebellion. His forces devastate the Iron Islands, Balon’s eldest sons are killed, and Theon is taken hostage.

Balon’s rebellion is an abject failure that wins his people nothing but ash and dust. And yet, in the present day of the story, he is prepared to do it all over again. Theon brings his father a proposal from Robb, freshly crowned King in the North: they will join forces against House Lannister (which is running the realm–into the ground–in the wake of Robert’s death), allowing both Robb and Balon to grant their respective peoples independence from the Iron Throne. It’s everything Balon could want. He refuses, out of equal parts pride and spite.

Instead, he embarks on a series of maneuvers so mind-bogglingly misguided it’s a miracle no one beat Euron to the regicidal punch. Balon decides to attack the North, Robb’s homeland, the other region of Westeros trying to secede. He dispatches the majority of his forces under his brother Victarion to secure the chokepoint castle of Moat Cailin, preventing Robb from returning from his wars in the south…and then just leaves them there for months. He has no plan to conquer the interior, nor to prevent the thousands of fighting-age men still left in Stark territory from retaking Moat Cailin, nor even to deal with Winterfell–the capital of the North, its natural rallying point, and home to Robb’s brother and heir Bran (much more on him later). Only a series of increasingly unlikely domino falls involving Theon and Ramsay, none of which have anything to do with Balon’s decision-making, prevent the Ironborn from being kicked out of the North soon after they arrive. For the cherry on top, Balon only bothers to make diplomatic overtures to the Iron Throne after putting his invasion plan into action. As Tywin Lannister points out, why should he grant the Ironborn independence in exchange for them attacking the North when they’re already attacking the North? Ultimately, Balon dies no closer to his goal than when he started.

art by Ertaç Altınöz

All of this is relevant to Euron’s story because this the context in which his takeover of the Iron Islands takes place. The point is not merely that Balon is a terrible strategist, nor that he can’t get past the humiliation of his defeat and his grief for his sons. The point is that the Old Way’s promise to make the Iron Islands great again has repeatedly gone unfulfilled, in large part because of the blind spots inculcated by that worldview. Balon doesn’t think he needs an actual plan to conquer the North, because his ideology tells him that the Northmen are weak “greenlanders” who can’t possibly stand up to his ubermensch pirate buddies. So what if the Northmen have plenty of strong castles to hide in and the Ironborn lack the equipment, numbers, and patience to properly besiege them? So what if the last time I tried this, it brought my people not freedom but fire and blood? The Drowned God will deliver us our holy kingdom, any day now…any day now, he can’t just leave it there drowned, among the waves…

The Old Way’s grip is strong enough on its supporters that they are able to bury its blatant failure in denial. But as A Feast for Crows begins, they can’t deny it any longer. The king is dead. Long live the king.

Aeron was almost at the door when the maester cleared his throat, and said, “Euron Crow’s Eye sits the Seastone Chair.”

The Damphair turned. The hall had suddenly grown colder. The Crow’s Eye is half a world away. Balon sent him off two years ago, and swore that it would be his life if he returned. “Tell me,” he said hoarsely.

The most significant and distinctive element of Euron’s character is his connection to cosmic horror. When he is introduced, however, he’s concealing that side of him–quite literally, with an eyepatch. The Euron of Feast is primarily engaged in politics. As with Cersei Lannister and her crony Qyburn in that same book, sorcery and the torment that goes with it is happening behind the scenes. It explodes into full view in “The Forsaken” (a released chapter from The Winds of Winter), at which point the true shape and scope of Euron’s story becomes horribly clear. But that’s not the story Martin is telling on the Iron Islands in A Feast for Crows.

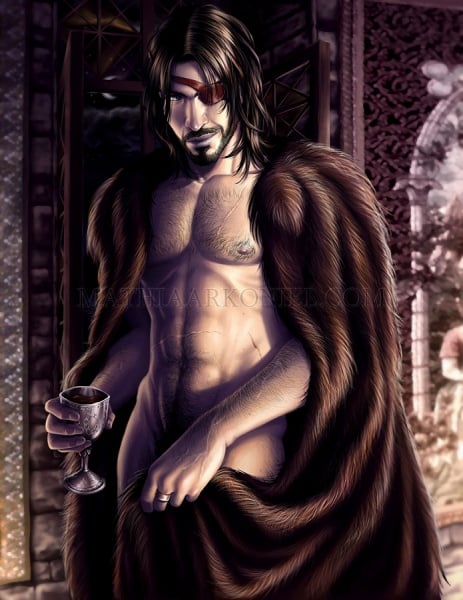

art by Mathia Arkoniel

The story he is telling is about how the Old Way is so bankrupt that an obvious supervillain who could not possibly care less about it can take over without breaking a sweat. The central point-of-view characters are Euron’s younger brothers Aeron and Victarion, both of whom despise him, but are so locked into the Old Way framework that they can’t effectively resist his coup. (Their niece Asha is also a POV in this storyline, making her own claim to her father’s throne, but she doesn’t orbit Euron like Aeron and Victarion do.) Everything unravels at the election to choose Balon’s successor, known as the kingsmoot, in which various candidates make their pitch as to how the Ironborn should escape from their self-inflicted hell…only for the devil himself to strut in and win them over with lies of Arbor gold. Before Martin uses Euron as the eye of the alchemical apocalyptic storm, he uses him as a vessel of cultural critique, focused through the lens of his brothers.

art by Matt Olson

Victarion Greyjoy is miserable, and doesn’t know why. He keeps trying to fill the hole inside with sex and battle and the stirring sight of his beloved Iron Fleet, but it never lasts. He watches with jealousy as Euron smiles his way through life (and beyond). Why is he happy, while I am not? Because Euron saw through the Old Way’s lies from childhood forward, and Victarion has allowed them to strangle his soul. After Euron seduced Victarion’s wife (or so he says; knowing Euron, he may have raped her), Victarion beat her to death with his bare hands, because the Old Way voice in his head told him that’s what he had to do in order to stay a proper Ironborn man. He sobbed as he did it. He tells himself nowadays that he had no choice.

Victarion stands in for all the Old Way Ironborn, marching themselves and their families into the abyss again and again. They never stop to wonder if what has left them so unsatisfied is the way they lead their lives. As long as they acknowledge only external obstacles, never internal, they will never find peace. Hence Victarion’s pitch at the kingsmoot: “All you’ll get from me is more of what you got from Balon. That’s all I have to say.” All Balon gave his people was defeat, delusion, and death. Victarion ate it up unquestioningly and is asking for seconds.

Aeron Greyjoy, by contrast, is all internal obstacles, and so gives the reader a different angle on the Old Way’s failures and how Euron takes advantage of them. When Aeron was a child, Euron repeatedly molested him and their brother Urrigon. It seems to have been public knowledge. Nobody did anything about it. As Aeron grew up, he looked everywhere for a way to drown the pain and anger and fear. At first, he relied on booze and battle, staggering his way from one pissing contest (literal and otherwise) to another. Like the Old Way Ironborn in general, he papered over the darkness with appeals to Valhalla, and it didn’t work. Aeron is taken prisoner as part of big brother Balon’s first rebellion, and even that doesn’t break through his walls. What does is a near-drowning experience, after which he finds religion.

art by Winona Nelson

Like many ideologies of racial supremacy, the Old Way leans heavily on religious dogma to justify itself. The faith of the Drowned God preaches that drowning and being resurrected by a priest is central to what makes the Ironborn better than everyone else: “what is dead may never die, but rises again, harder and stronger.” (It’s almost as if they’re being prepared to serve Euron well into the afterlife, the pharaoh dragging his screaming servants into the grave and beyond…)

The Ironborn plot of A Feast for Crows begins with Aeron (known post-rebirth as “Damphair”) performing CPR on his newest follower after drowning him, framing it as bringing the young man back from the dead via god’s will. Damphair doesn’t actually have a mainline to the divine. The voice he hears in his head is his own, a defense mechanism he’s created to shield him from Euron. That becomes practically explicit in “The Forsaken,” in which Aeron’s god is unable to tell him who should claim the Seastone Chair in Euron’s place, and he immediately falls back on the answer he wanted all along. As the priest puts it, he rebuilt his life around “two mighty pillars,” his Drowned God and his rebel brother Balon. Then his abuser comes home to kill the latter and viciously deconstruct the former.

“We shall have no king but from the kingsmoot.” The Damphair stood. “No godless man—”

“—may sit the Seastone Chair, aye.” Euron glanced about the tent. “As it happens I have oft sat upon the Seastone Chair of late. It raises no objections.” His smiling eye was glittering. “Who knows more of gods than I? Horse gods and fire gods, gods made of gold with gemstone eyes, gods carved of cedar wood, gods chiseled into mountains, gods of empty air . . . I know them all. I have seen their peoples garland them with flowers, and shed the blood of goats and bulls and children in their names. And I have heard the prayers, in half a hundred tongues. Cure my withered leg, make the maiden love me, grant me a healthy son. Save me, succor me, make me wealthy . . . protect me! Protect me from mine enemies, protect me from the darkness, protect me from the crabs inside my belly, from the horselords, from the slavers, from the sellswords at my door. Protect me from the Silence.”

Aeron calls the kingsmoot in response, assuming that Victarion will win. Just look at him, the hulking embodiment of the Old Way! Aeron takes refuge in the Old Way as Balon always did, assuming it will save him and his people from his abuser. And just like Balon, he is wrong. The devil triumphs, and not by possessing or zombifying anyone. He triumphs by winning an election. He wins that election by understanding not only that the Old Way is rotten, but that everyone knows it. The boldest ones are even starting to admit it.

“We cannot stand alone against all Westeros. King Robert proved that, to our grief. Balon would pay the iron price for freedom, he said, but our women bought Balon’s crowns with empty beds. My mother was one such. The Old Way is dead.”

Asha carries this argument forward at what she calls her queensmoot:

“Nuncle says he’ll give you more of what my father gave you. Well, what was that? Gold and glory, some will say. Freedom, ever sweet. Aye, it’s so, he gave us that … and widows too, as Lord Blacktyde will tell you. How many of you had your homes put to the torch when Robert came? How many had daughters raped and despoiled? Burnt towns and broken castles, my father gave you that. Defeat was what he gave you. Nuncle here will give you more. Not me.”

“What will you give us?” asked Lucas Codd. “Knitting?”

“Aye, Lucas. I’ll knit us all a kingdom.” She tossed her dirk from hand to hand. “We need to take a lesson from the Young Wolf, who won every battle…and lost all.”

“A wolf is not a kraken,” Victarion objected. “What the kraken grasps it does not lose, be it longship or leviathan.”

“And what have we grasped, Nuncle? The north? What is that, but leagues and leagues of leagues and leagues, far from the sound of the sea? We have taken Moat Cailin, Deepwood Motte, Torrhen’s Square, even Winterfell. What do we have to show for it?” She beckoned, and her Black Wind men pushed forward, chests of oak and iron on their shoulders. “I give you the wealth of the Stony Shore,” Asha said as the first was upended. An avalanche of pebbles clattered forth, cascading down the steps; pebbles grey and black and white, worn smooth by the sea. “I give you the riches of Deepwood,” she said, as the second chest was opened. Pinecones came pouring out, to roll and bounce down into the crowd. “And last, the gold of Winterfell.” From the third chest came yellow turnips, round and hard and big as a man’s head. They landed amidst the pebbles and the pinecones. Asha stabbed one with her dirk. “Harmund Sharp,” she shouted, “your son Harrag died at Winterfell, for this.” She pulled the turnip off her blade and tossed it to him. “You have other sons, I think. If you’d trade their lives for turnips, shout my nuncle’s name!”

“And if I shout your name?” Harmund demanded. “What then?”

“Peace,” said Asha. “Land. Victory. I’ll give you Sea Dragon Point and the Stony Shore, black earth and tall trees and stones enough for every younger son to build a hall. We’ll have the northmen too … as friends, to stand with us against the Iron Throne. Your choice is simple. Crown me, for peace and victory. Or crown my nuncle, for more war and more defeat.”

art by Magali Villeneuve

The Old Way led Victarion to murder his beloved wife, just as Euron knew it would. The Old Way ground generations in its gears, and for what? Pebbles and pinecones. The Old Way didn’t protect anyone from Euron, because for Euron, the Old Way was training wheels. Cute, even. Yet even as the dream decays, it retains at least some appeal for most, and that’s a delicate needle to thread.

Thread it Euron must, however, because his master plan calls for ships. And cannon fodder. Ideally, the cannon fodder will supply their own ships. The Ironborn offer Euron a stepping stone to his dreams, a valuable layer of kindling for the interdimensional pyre. But in order to claim them, he must pretend to believe in their dreams as well, like any worthwhile devil. As Brown Ben Plumm puts it to Daenerys Targaryen when she sets out to rule the conquered city of Meereen: “Man wants to be the king o’ the rabbits, he best wear a pair o’ floppy ears.”

art by Amok

The floppy rabbit ears being, in Euron’s case, his eyepatch. We need to talk about the eyepatch. In isolation, it might seem like evidence that Euron is a half-baked villain, so undistinguished that the author fell back on the most tired of pirate cliches. The eyepatch takes on a greater meaning in context with Euron’s characterization as a whole. He is not wearing it because he thinks it makes him look cool. He’s wearing it because he knows the people around him think it looks cool. It’s a disguise, a lure, a friendly bobbing light pulling you in close so that by the time you see the angler fish’s teeth, it’s too late. Euron has to look like the ultimate Ironborn to win his election, and this is his sarcastic image of what the ultimate Ironborn looks like. It’s a set of scare quotes, the weaponized deployment of a worn-out identity, a parodic politician-purr practiced til it drowns out the tombstone-teeth cackle.

In short, it’s a pirate costume.

Martin isn’t falling back on the trope, he’s showing us how Euron is falling back on the trope. Whether you’re cheering the patch or mocking it, he’s kept you from asking the important question: what’s behind it? What’s he hiding from his followers? When the last of them falls asleep, what dreams climb down from inside that Trojan Horse?

Unfortunately for Euron, simply gesturing at the collective portrait of his forebears and then pointing back at himself in an exaggerated fashion proves not quite enough to rise to power. As such, he has to do the unthinkable for a man accustomed to psychically controlling everyone around him: campaign.

“The Silence returned with holds full of treasure. Plate and pearls, emeralds and rubies, sapphires big as eggs, bags of coin so heavy that no man can lift them . . . the Crow’s Eye has been buying friends at every hand.”

The downside of a mute crew is having to be your own hypeman, but Euron is up for the challenge. The challenge is that his primary claim to fame is going somewhere no one sane would dream to tread. Namely, Valyria: once the cradle of dragonlords, now a festering waste full of demons and plagues. Both the cataclysmic event itself and the blasted land resulting are referred to as the Doom. Curses are rumored to attach themselves to anyone foolish enough to come calling. There’s reason to believe Euron didn’t actually do so (his omnipresent smile vanishes when Rodrik “the Reader” Harlaw doubts his story), but that’s irrelevant to how he deploys his resume politically:

He laughed. “Godless? Why, Aeron, I am the godliest man ever to raise sail! You serve one god, Damphair, but I have served ten thousand. From Ib to Asshai, when men see my sails, they pray.”

The priest raised a bony finger. “They pray to trees and golden idols and goat-headed abominations. False gods . . .”

“Just so,” said Euron, “and for that sin I kill them all. I spill their blood upon the sea and sow their screaming women with my seed. Their little gods cannot stop me, so plainly they are false gods. I am more devout than even you, Aeron. Perhaps it should be you who kneels to me for blessing.”

Euron expands on this argument at the kingsmoot itself, showing off one of his shiny new Valyrian toys just to get everyone to shut up and listen:

Sharp as a swordthrust, the sound of a horn split the air.

Bright and baneful was its voice, a shivering hot scream that made a man’s bones seem to thrum within him. The cry lingered in the damp sea air: aaaaRREEEEeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee.

All eyes turned toward the sound. It was one of Euron’s mongrels winding the call, a monstrous man with a shaved head. Rings of gold and jade and jet glistened on his arms, and on his broad chest was tattooed some bird of prey, talons dripping blood.

aaaaRRREEEEeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee.

The horn he blew was shiny black and twisted, and taller than a man as he held it with both hands. It was bound about with bands of red gold and dark steel, incised with ancient Valyrian glyphs that seemed to glow redly as the sound swelled.

aaaaaaaRRREEEEEEEEEEEEeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee.

It was a terrible sound, a wail of pain and fury that seemed to burn the ears. Aeron Damphair covered his, and prayed for the Drowned God to raise a mighty wave and smash the horn to silence, yet still the shriek went on and on. It is the horn of hell, he wanted to scream, though no man would have heard him. The cheeks of the tattooed man were so puffed out they looked about to burst, and the muscles in his chest twitched in a way that it made it seem as if the bird were about to rip free of his flesh and take wing. And now the glyphs were burning brightly, every line and letter shimmering with white fire. On and on and on the sound went, echoing amongst the howling hills behind them and across the waters of Nagga’s Cradle to ring against the mountains of Great Wyk, on and on and on until it filled the whole wet world.

“We are the ironborn, and once we were conquerors. Our writ ran everywhere the sound of the waves was heard. My brother would have you be content with the cold and dismal north, my niece with even less … but I shall give you Lannisport. Highgarden. The Arbor. Oldtown. The riverlands and the Reach, the kingswood and the rainwood, Dorne and the marches, the Mountains of the Moon and the Vale of Arryn, Tarth and the Stepstones. I say we take it all! I say, we take Westeros.” He glanced at the priest. “All for the greater glory of our Drowned God, to be sure.”

For half a heartbeat even Aeron was swept away by the boldness of his words. The priest had dreamed the same dream, when first he’d seen the red comet in the sky. We shall sweep over the green lands with fire and sword, root out the seven gods of the septons and the white trees of the northmen …

“Crow’s Eye,” Asha called, “did you leave your wits at Asshai? If we cannot hold the north—and we cannot—how can we win the whole of the Seven Kingdoms?”

“Why, it has been done before. Did Balon teach his girl so little of the ways of war? Victarion, our brother’s daughter has never heard of Aegon the Conqueror, it would seem.”

“Aegon?” Victarion crossed his arms against his armored chest. “What has the Conqueror to do with us?”

“I know as much of war as you do, Crow’s Eye,” Asha said. “Aegon Targaryen conquered Westeros with dragons.”

“And so shall we,” Euron Greyjoy promised. “That horn you heard I found amongst the smoking ruins that were Valyria, where no man has dared to walk but me. You heard its call, and felt its power. It is a dragon horn, bound with bands of red gold and Valyrian steel graven with enchantments. The dragonlords of old sounded such horns, before the Doom devoured them. With this horn, ironmen, I can bind dragons to my will.”

This is a brilliant campaign strategy, because Euron is taking his weakness (voracious sorcerous globetrotting) and spinning it as a strength. My travels don’t prove I have no interest in Ironborn culture, comrades! They prove I’ve been the ultimate emissary of the Old Way, sowing our seeds far wider than my brothers ever dared. All across the seven seas I’ve shed blood as tribute to your god–my god, beg pardon. Vote Crowseye! And it works perfectly, as he knew it would.

art by Mathia Arkoniel

They would’ve listened even without Dragonbinder (the hellhorn’s name), but now they’ll never forget it, and never remember anything else that was done or said. Beneath the metaphysical fireworks, Dragonbinder is Euron’s way of letting you know that the party didn’t start until he walked in. It’s a microcosm of the invasive colonizing instinct with which he has approached every interaction in life, be it with another individual, a group, an ideology, an entity of alchemy and dream…

…or you. Yes, reading this, you. What were you doing just now that was so important? What were you thinking, saying, before my hellhorn rang true between your eyes? Do you remember? Did you even exist? Can you be sure? What if there is only Euron? What if there was only ever Euron? What if there will only ever be Euron?

Feed Euron, or be eaten.

Euron Greyjoy climbed the hill slowly, with every eye upon him. Above the gull screamed and screamed again. No godless man may sit the Seastone Chair, Aeron thought, but he knew that he must let his brother speak. His lips moved silently in prayer. Asha’s champions stepped aside, and Victarion’s as well. The priest took a step backward and put one hand upon the cold rough stone of Nagga’s ribs. The Crow’s Eye stopped atop the steps, at the doors of the Grey King’s Hall, and turned his smiling eye upon the captains and the kings, but Aeron could feel his other eye as well, the one that he kept hidden.

“IRONMEN,” said Euron Greyjoy, “you have heard my horn. Now hear my words. I am Balon’s brother, Quellon’s eldest living son. Lord Vickon’s blood is in my veins, and the blood of the Old Kraken. Yet I have sailed farther than any of them. Only one living kraken has never known defeat. Only one has never bent his knee. Only one has sailed to Asshai by the Shadow, and seen wonders and terrors beyond imagining …”

“If you liked the Shadow so well, go back there,” called out pink-cheeked Qarl the Maid, one of Asha’s champions.

The Crow’s Eye ignored him. “My little brother would finish Balon’s war, and claim the north. My sweet niece would give us peace and pinecones.” His blue lips twisted in a smile. “Asha prefers victory to defeat. Victarion wants a kingdom, not a few scant yards of earth. From me, you shall have both.”

Asha and Victarion unknowingly created Euron’s ideal Venn diagram. They both stood so effectively against each other that they opened up precisely the political space Euron needed to make his two-fisted critique of both Old and New Way. Yet even as he pulls off his grand charade, he can’t help tipping his hand.

Asha laughed aloud. “A horn to bind goats to your will would be of more use, Crow’s Eye. There are no more dragons.”

“Again, girl, you are wrong. There are three, and I know where to find them. Surely that is worth a driftwood crown.”

“Surely that is worth a driftwood crown” rips back the iron curtain, revealing Euron’s contempt for his people as ants beneath his cosmic boot like everyone else. Yet only Aeron sees the wells drained dry all around the Crow’s Eye. The priest stands alone in the abyss, his god mute like Euron’s crew, the cheers all around him sounding only of silence. He is forced to personally crown his abuser. What makes Victarion and Aeron different in terms of their perspective on Euron is that Victarion thinks of Euron as pure chaos: formless, directionless, naught but rot. What Aeron knows and fears is the signal inside the noise, the new order emerging from behind the eyepatch.

art by Zippo514

If Euron’s true import to the Song is tied to the Crow’s Eye hiding back there, why take us through a book’s worth of eyepatch-based politics that Euron himself sees merely as an aggravating means to an end? By starting with the “smiling eye,” Martin shows us how easily we can be won over by monsters as long as they know which levers to press. An apocalyptic force washing over political disputes can make for a fine story. But how much more insidious, how much more relevant, to tell a story about that apocalyptic force conquering the politics from within!

In “The Forsaken,” Euron reveals to Aeron not only that he had Balon killed, but that he personally murdered two more of their brothers as a child. Harlon Greyjoy had an advanced case of the disease greyscale, rendering him immobile; Euron pinched his nose shut and watched the emptiness eat out his eyes. We have yet to learn the details of what happened to Robin Greyjoy, but Euron’s contemptuous mention of the boy’s “soft head” suggests he took advantage of his little brother’s mental disability to test his psychic powers, up to the point of murder. Ramsay Snow, the Bastard of Bolton, believes his atrocities prove he belongs in his family’s vampiric history. Euron, too, has been auditioning in horror from an early age, but with his eyes on a much higher stage.

Yet the intimacy achieved by focusing his story through the lens of his brothers is vital, because it provides a structure to Euron’s character beyond that of the sudden storm, as he describes himself. At every turn, he positions himself as the void’s silence in response to his brothers’ increasingly desperate questions. He is a cancerous counter-narrative let loose in a world they wish to order, proving that they’re wrong about their people, their god, their very selves. His domination of them is a preview of how he’d dominate all. They are the egg from which he hatches, left broken.

art by Malky Dungeon

A Feast for Crows is about how war has poisoned Westeros. There is a window for renewal and rebirth in the wake of the killing fields of A Storm of Swords, but it goes forsaken. The sparrow movement marches on the elites in the name of those sacrificed to the god of the graveyard (literally bringing carts of bones with them to the capital), but winds up punishing The Wicked Queen Cersei mostly for being a woman with political and sexual power, rather than for her crimes against the people. Cersei’s brother and lover Jaime tries his best to bring peace to the countryside he helped set ablaze, but everywhere he turns he finds the bloody past (his own, his family’s, and that of all Westeros) overcoming his gestures. Doran Martell, Prince of Dorne, pays lip service to peace in preventing his nieces from violently avenging the death of his brother Oberyn. At book’s end, he reveals that he’s far more committed to vengeance than they are. His son Quentyn dies in a cyclone halo of dragonflame at the end of the next book, trying to make Dad proud. The last hero screams as he burns. The first hero, Barristan Selmy, stares at the body; the pools of pus where Quent’s eyes used to be stare back in silent judgment. Then the old man covers the poor kid up, and resumes the war.

Pull back the camera and you’ll find the Faceless Men, introduced in earlier novels but fleshed out in Feast as Arya Stark travels to their headquarters, the House of Black and White. They are peerless assassins for hire; it is strongly hinted that Euron employed their services to kill Balon. Their true thematic import to A Feast for Crows, however, is as a death cult. They stare out from behind their masks made of corpses at a novel and a world obsessed with death. They argue that every god worshipped in all these far-flung locations is one god, that of the grave, and he listens all too well.

Nothing can grow from this soil. The closest thing to a ray of hope in the book is the man digging doggedly into the dirt anyway at an isolated monastery. He is almost certainly Sandor Clegane, burying the Hound for good. But he’s still digging graves, not planting trees, and as apocalypse looms, the people in charge seem just as determined as ever to give him plenty of work.

art by Todd Ryan White

All of it, all of it, is a red carpet rolling out for the dark lord. Euron was there when Quentyn died, on the astral plane with the hero’s soul raw and wriggling between his teeth. He stopped chewing long enough to mouth gleefully along with Barristan’s epitaph: Not all men are meant to dance with dragons. But I am. The last hero is dust, and I live.

Westeros is a feast for crows, aye.

Westeros is a feast for crowseye.

Westeros is a feast for crows…and all that’s left is I.

The war in its death throes birthed Euron; he ate his way out of it and wears its face as a mask. To look like he belongs. A cancer cell painted over with blood and soil; hell, he fits right in. The world ends because we end, holding our “mighty pillars” high above our head even as they crumble down on us, even as the waters rise from the holes they leave behind, around our ankles, our knees, our throats. Next to that, Euron’s failure to be a psychologically complex, relatably tortured villain is not the point. Euron isn’t really the point, because there’s nothing left inside. It’s the water; it’s the mirror. It’s what he represents. He’s the bill come due. Decay given form. A monster wearing a pirate suit, and the true essence of horror is not that there are monsters at the door.

It’s that we’re going to let them in.

art by Mathia Arkoniel

And that’s where we pause our monster, tentacles tip-twitching impatiently on the doorknob, to ask the pressing question: why is he like this?

Euron stood by the window, drinking from a silver cup. He wore the sable cloak he took from Blacktyde, his red leather eye patch, and nothing else. “When I was a boy, I dreamt that I could fly,” he announced. “When I woke, I couldn’t … or so the maester said. But what if he lied?”

Victarion could smell the sea through the open window, though the room stank of wine and blood and sex. The cold salt air helped to clear his head. “What do you mean?”

Euron turned to face him, his bruised blue lips curled in a half smile. “Perhaps we can fly. All of us. How will we ever know unless we leap from some tall tower?” The wind came gusting through the window and stirred his sable cloak. There was something obscene and disturbing about his nakedness. “No man ever truly knows what he can do unless he dares to leap.”

“There is the window. Leap.” Victarion had no patience for this. His wounded hand was troubling him. “What do you want?”

“The world.” Firelight glimmered in Euron’s eye. His smiling eye.

Every supervillain worth their salt has an origin story for which they’ll summon the spotlight and monologue. They are called back, moths to the flame of the moment in which I could have been you but knew better. That’s why I’m here at the top of the tower, while your fingers are slipping off the edge beneath me one by one. Euron pulls back the patch to reveal the eye of the storm: a dream. He lives inside a dream.

King Bran Stark, protagonist of ASOIAF, is visited in his dreams by a three-eyed crow. The crow proves to be an astral projection of the sorcerer Brynden Rivers, better known as Bloodraven. He lingers, dreamlord of a faded frozen far-flung faerie fort, having long outlasted his mortal lifespan by threading himself through the living bark of the world tree. His accomplishments and abominations alike in the wars of his youth play out on the inside of his dessicated eyelids. Winter is coming, the ghosts whisper as they burn in time, the long night that never ends.

Bloodraven labors to forge a sword in the darkness. So many swords in Westeros, so many would-be heroes! Everyone’s the star of their own song until they see the true star above them, an eye in the sky; the songs die on their lips. Only one in a million will meet its gaze. But that’s the one I need. I will find the third eye, and open it, and sail the world through. I will dream for my chosen one a dream of the end. A set of jaws around the world, frozen but thawing; a final hunt in the forest of songs and screams. I will teach them to fly, raise them high, then show them why.

Surely they will cry out in fear.

Bran cried out in fear.

Euron cried out in awe.

He saw a cool intelligence uncoiling itself, no longer human; he saw the Other, and smiled in recognition.

The abyss smiled back. It smiled wider and wider every time he returned, feeding it his family, his people, his soul. Euron grew into an ice-pale nightwalker like Bloodraven before him, Westeros’ own Freddy Krueger hunting Daenerys through her dreams, wearing her husband’s face to trick her into bed…only for her to find too late that his penis is cold as ice. Why call himself “Crow’s Eye,” if not as an ironic honor to the crow who opened his third eye? Why else adopt, as his personal banner, the image of birds crowning a sorcerous eye? Euron is Bloodraven’s bad seed, the antagonist made in the protagonist’s mold. The three-eyed crow laid a rotten egg. It’s hiding behind an eyepatch, and it’s almost ready to hatch. In his efforts to save the world, Bloodraven sealed its doom.

art by drafturgy

Euron tells us where he came from and where he’s going with his first line of dialogue: “King Crow’s Eye, brother.” It was the crow, and the eye; it was the crow’s eye (the crow’s aye?) that made me king. Of what? You for a start, little brother. We’ll build my way back up to the kingdom of heaven from there.

This is the core of Euron’s character, snapping all the portentous imagery and free-floating dread around him into a coherent structure. Bloodraven opened his third eye as a child, showing him a world where he could be more than yet another Greyjoy heel eking out a living by bumrushing fishing villages before returning to his grim damp islands to die. He could climb higher than his twice-crowned brother ever dreamed. Bran Stark, the protagonist, was thrown from a tall tower. Euron Greyjoy, the antagonist, leapt.

But from what tower?

art by Tommy Scott

Valyria was born of sorcery, and Valyrian sorcery was rooted in fire and blood. The dragonlords who ruled the Freehold fed their magical volcanoes a steady diet of slaves imported from all over the continent of Essos, imperialist conquest as blood sacrifice on a massive scale. The Fourteen Flames fueled the empire and then burst like overripe fruits, drenching Valyria in doom. “Sorcery is a sword without a hilt…there is no safe way to wield it.” In climbing the fiery ladder, the dragonlords shed their humanity. Valyria is a monster’s den, both before and after its fall.

Once, though, the Valyrians had no such powers. No Fourteen Flames, no blood sacrifice, no dragons. Once they herded sheep, a modest harmless living in the air pockets left behind by older empires.

And then…and then…!

Someone crossed the line. Someone split the atom, touched the monolith, spoke the Word into the void and heard a voice speak back. Someone made a deal with that voice, and every door at the end of every path turned red. That first dragontamer wasn’t inheriting a legacy, following the fiery singing in their veins like Daenerys bringing the beasts back from beyond. They had to create that legacy, and Daenerys tells us how they did it: “The dragonlords of old Valyria had controlled their mounts with binding spells and sorcerous horns.”

Euron is that first dragonlord reborn, Azor in the Ahaiest. He will rise from the muck to steal fire out from under the nose of the gods. The pre-draconic Valyrians were similar to the Ironborn as they stand upon the prodigal crow’s return. They will be another backwater catapulted to empire on dragonback. And they will do so the same way the first Valyrians did: with a song, a sudden swell of sound from a hellhorn. This power is not hidden behind strong castle walls, nor bound inside special genes. It sits there, a flowering fragment amidst the ruin, waiting for me. I alone can breathe life into the flame. My loyal followers will warm themselves by the fire…come, sit a little closer…closer now…

So he tells them. And in truth, Euron would probably be far more at home among the dragonlords of old than would Daenerys herself, what with her distressing insistence on freeing slaves. The trick to Euron’s fanboy worship of Valyria, however, is that his Valyria is not that of the straight roads and shining towers. It’s Valyria of the demon-scalded sea; Valyria as it exists now, not in the romantic image of yesteryear. The smiling eye promises the empire, but the Crow’s Eye thirsts only for doom. Most people would say Valyria’s reign ended with the Doom. Euron would say that was only the beginning. Daenerys may be the heir of Old Valyria by blood, but it is Euron in spirit. They came so close to being able to reach up and claw at the face of god. I will finish what they started, because unlike them, I know going in that I will not be human by the end. I look forward to it. I have waited so long.

His people, however, prefer the fruits of their infernal labors to Euron’s war of woe. The Ironborn shout him down when he tries to lead them to Slaver’s Bay to claim Daenerys and her three dragons. So Euron sends his brother Victarion, God’s perfect tool. Victarion decides to take Daenerys for his own bride, as vengeance for the wife he believes Euron made him kill. The Iron Suitor spends the entire trip eastward certain that he’s finally got one over on Euron. He proclaims this loudly and proudly to a mute slave known only as the dusky woman, a “gift” from Euron. When Victarion initially refused her, Euron oh-so-casually mentioned that she’d be killed in that case. Victarion weakened and agreed, taking her east, having sex with her repeatedly, and even allowing her to care for his battle wound. The wound festers. Victarion blames his maester instead of the dusky woman, because in spite of the obviousness of Euron’s reverse-psychology ploy, in spite of Victarion telling himself that “Euron’s gifts are poisoned,” the core of his character is being unable to perceive the truth even when staring it in the face. The dusky woman is Euron’s agent, or perhaps even his host. After all, as Bloodraven tells Bran, only skinchangers–those with the ability to possess other beings, including other humans–qualify to be his messiah. Is this why Euron silenced the crew of the Silence, to keep hidden the full fruit of the hideous experiments he’d begun on Robin? As Bran puts it when giving in to abomination: “no one must ever know.”

Victarion was also lent Dragonbinder. He’s falling in love with it. As he steams into battle at Slaver’s Bay in his released Winds of Winter chapter, he selects three slaves to blow the horn upon their arrival, thus hopefully bewitching one or more of Daenerys’ dragons. But just for a moment, Victarion feels the temptation well up to blow the horn himself. It will overtake him, because it’s the same siren call to which he keeps surrendering: anything to feel like a bigger better man than Euron. This temptation will strand Victarion in hell, because to blow Dragonbinder is to die. Victarion knows this; he beheld the eye-watering fate of the hornblower at the kingsmoot.

“The horn was smoking after. The mute had blisters on his lips, and the bird inked across his chest was bleeding. He died the next day. When they cut him open his lungs were black.”

But if he was a rational man, he wouldn’t have beaten his beloved wife to death just because the Old Way said so. He will fling himself headfirst into the void to defeat Euron, and die knowing he was a cheap imitation of Big Brother. Euron got deep in the void’s good graces long ago, and the more Victarion struggles to escape Euron’s shadow, the more he winds up contributing to Euron’s victory.

“I have seen you in the nightfires, Victarion Greyjoy. You come striding through the flames stern and fierce, your great axe dripping blood, blind to the tentacles that grasp you at wrist and neck and ankle, the black strings that make you dance.”

art by Lukasz Jaskolski

To move forward with fire alone, however, would be to close a half-finished book. How do we reconcile Euron the would-be dragonlord out to recreate Valyria’s Doom with Euron the rotten egg laid by the three-eyed crow, destined to hatch in accordance with the icy Other of northern Westeros? How do we reconcile fire and ice? They’re opposites, after all! Lady Melisandre certainly thinks so, anyway:

“The truth is all around you, plain to behold. The night is dark and full of terrors, the day bright and beautiful and full of hope. One is black, the other white. There is ice and there is fire. Hate and love. Bitter and sweet. Male and female. Pain and pleasure. Winter and summer. Evil and good.” She took a step toward him. “Death and life. Everywhere, opposites. Everywhere, the war.”

But Melisandre also thinks that Stannis Baratheon, aforementioned crowned firebug, is the sword in the darkness, and that Bran and Bloodraven are champions of the Other. In other words, Melisandre is generally wrong. Martin specifically proves her wrong about duality again and again.

“I would say my parts are mixed, m’lady. Good and bad.”

“A grey man,” she said. “Neither white nor black, but partaking of both. Is that what you are, Ser Davos?”

“What if I am? It seems to me that most men are grey.”

“Do you hate her?”

“Almost as much as I love her.”

“If ice can burn … then love and hate can mate.”

“People ask me how Game of Thrones is gonna end, and I’m not gonna tell them … but I always say to expect something bittersweet in the end.”

The oppositional dichotomy is fiction. The two at their core are one. Ice is Fire. That crossover point is where the world is broken and remade. Just ask Jon Snow–or rather, ask his adoptive father Ned Stark about the wonder and terror of seeing ice and fire revealed as one. It offers the ultimate power, but also the ultimate responsibility: that of a parent given care of a child. Which do you choose?

Ned chose responsibility. We remember him fondly for a reason. Euron is nothing more (but nothing less) than the endgame of choosing power, every time, always. Valyria is radioactive ash by the time the story begins. The Other rarely appears directly. Both are still shrouded in mystery after the conclusion of Game of Thrones. If you want to see them as they really are, if you want to know what happens when frozen fire slips under your skin and replaces you with it, look no further than Euron Greyjoy.

Every other song in the Song has a foundation, a base from which it springs. Fire and Ice. Winterfell and Dragonstone. I want power to keep my family safe, I want power to set the realm to rights, I want power because I very much enjoy sex and violence. But Euron wants power like a match wants a light, and his third eye has allowed him to see through every wall surrounding every narrative and realize he doesn’t have to choose. In this regard, he is the photo negative not of Bran Stark, but Jon Snow: forever caught between worlds, winding up wanting nothing, yet still always having to choose. Euron, as he declares at the kingsmoot, will take it all.

He’s got a horn to catch fire. But what about ice? For that, we must return to our monster where we paused him, on the threshold, about to reveal himself in full.

After cementing his power among the Ironborn, Euron dispatches Victarion to the east and allows Asha to flee into exile in the north. Aeron stalks away from the kingsmoot declaring that he will stir up a rebellion among the common people, which will unseat the godless man from the Seastone Chair. But as we learn in “The Forsaken,” Euron had other plans for his favorite victim.

Aeron Damphair had struggled back to shore, full of fierce resolve. He would bring down Euron, not with sword or axe but with the power of his faith. Padding lightly across the stones, his hair plastered black and dank across his brow and cheeks, he stopped for a moment to push it back out of his eyes.

And that was where they took him, the mutes who had been watching him, waiting for him, stalking him through strand and spray. A hand clapped down across his mouth and something hard cracked against the back of his skull.

The next time he had opened his eyes, the Damphair found himself fettered in the darkness. Then came the fever and the taste of blood in his mouth as he twisted in the chains, deep in the bowels of Silence.

“The Forsaken” is a peerless portrait of apocalypse, stranding us in the Long Night from its opening line forward:

It was always midnight in the belly of the beast.

Aeron starves, and is nibbled by rats. He is deprived of his clothes and the company of his fellow man. The ocean pours into his cage on the high tide to make his wounds sing shrilly. His grasp on self and sanity wears thin in the dark. There’s a clear parallel to the torture that befalls Theon in Ramsay’s clutches, right down to the rats. Just as Ramsay forces Theon to act as his emissary at Moat Cailin, Euron demands that Aeron become his priest instead. Just as Ramsay deliberately deprives Theon of that which means most to him (his penis), Euron always circles back to Aeron’s last mighty pillar.

“All gods are lies, but yours is laughable. A pale white thing in the likeness of a man, his limbs broken and swollen and his hair flipping in the water while fish nibble at his face. What fool would worship that?”

The difference lies in the trajectory of our villains. The Bastard of Bolton is never more frightening than when he reveals himself as such, emerging from battle fog wearing armor shaped like a man in torment to claim Theon body and soul. When next we see Ramsay, even as we flinch from what he’s done to Theon in the interim, Martin is constantly drawing our attention to Ramsay’s follies, his political isolation, his utter failure to get his dad to love him. Even as Ramsay continues to rack up atrocities, he is demystified in terms of the image he has impressed in Theon’s mind. Theon sees Ramsay as a divine figure of worship and fear. Martin shows him to us as a pretentious bumbler desperate for scraps of power and approval.

Euron plays that record backwards, like any good satanist. He is least intimidating upon his introduction, the Crow’s Eye briefly winking at the audience from inside the interlocking layers of the smiling eye’s disguise. Euron’s in full method acting mode when we meet him, and only gradually are we allowed to understand the man behind the part he’s playing. “The Forsaken” strips everything down not to demystify Euron a la Ramsay, but to reveal that Aeron alone was right all along about Euron, that Euron is if anything worse than Aeron realized.

For all that Ramsay used and abused Theon every way he knew how, he could never get inside his victim’s head; this is in part why Theon was able to hold on to a scrap of himself, taking his own leap from a tall tower to escape both Ramsay and Reek. Euron has no such limitations. There is no safety, no border a person might think to set around themselves that he cannot and will not break. He can enter your mind. He can enter your dreams. And he found something in his travels that cracked open his nuclear-fired third eye even wider.

art by Alcoholic Rattle Snake

Shade of the evening is Martin’s catch-all psychedelic drug, the author weaving DMT imagery together with the crumbling whispers of soma and what seem like very fond acid flashbacks. We first encounter it when Daenerys visits the House of the Undying in the city of Qarth. The drug’s taste mirrors Euron’s boundary-breaking approach to villainy, a rainbow of flavors to mask the taste of corpseflesh:

The first sip tasted like ink and spoiled meat, foul, but when she swallowed it seemed to come to life within her. She could feel tendrils spreading through her chest, like fingers of fire coiling around her heart, and on her tongue was a taste like honey and anise and cream, like mother’s milk and Drogo’s seed, like red meat and hot blood and molten gold. It was all the tastes she had ever known, and none of them . . . and then the glass was empty.

More than any scene in which Euron actually appears (save “The Forsaken,” its evil twin), Daenerys’ adventure in Wonderland the House of the Undying captures why the Crow’s Eye exists as a character. The House of the Undying is George R.R. Martin’s brain on drugs. It’s a window onto the creative process, a mirror tilted by the god of this fictional universe so we can see his reflection. Daenerys enters the building through a door shaped like a mouth, in a wall shaped like a face. As she wanders its halls, she glimpses plot points half-complete, stillborn tragedies, keystone images flying free of their context. She sees the downfall of her family and the rise of her future lover and killer, all without knowing what she sees. She sees the simplest and most unsparing expression of the anti-war sentiments that flower into more detail elsewhere in the story, the seed from which they all spring:

In one room, a beautiful woman sprawled naked on the floor while four little men crawled over her. They had rattish pointed faces and tiny pink hands, like the servitor who had brought her the glass of shade. One was pumping between her thighs. Another savaged her breasts, worrying at the nipples with his wet red mouth, tearing and chewing.

The kings are assaulting the realm, villains one and all when you zoom out. But then Martin zooms back in, to show you the death of one of those kings, and ask you to mourn:

Farther on she came upon a feast of corpses. Savagely slaughtered, the feasters lay strewn across overturned chairs and hacked trestle tables, asprawl in pools of congealing blood. Some had lost limbs, even heads. Severed hands clutched bloody cups, wooden spoons, roast fowl, heels of bread. In a throne above them sat a dead man with the head of a wolf. He wore an iron crown and held a leg of lamb in one hand as a king might hold a scepter, and his eyes followed Dany with mute appeal.

From that beautiful contradiction, Martin built ASOIAF. And of course, Dany’s trip through the House of the Undying is the one and only time we hear those words spoken in the series: “the song of ice and fire.”

Dany emerges dazzled but baffled, hotly debating those around her about what she saw even as it slips away into sobriety. Not an atypical literary nor psychedelic experience, especially in combination. But it was an isolated one.

For Euron, it is a permanent state of affairs. His whole life has been a sky-high trip through the House of the Undying, third eye piercing the gossamer veil of meta-narrative wherever he goes. He knows he’s in a story, and delights in it because he can see the structure and reshape it at will.

The Undying see the puppet strings as well. That’s why they initially present themselves to Daenerys as the most on-the-nose gaggle of fantasy archetypes imaginable, down to wizards with pointy hats. It’s their equivalent of Euron’s eyepatch: a lure that mocks the imagery they’re exploiting. They embody the sense-heavy sublimity a young George R.R. Martin found in the stuff of fantasy…

“Fantasy is silver and scarlet, indigo and azure, obsidian veined with gold and lapis lazuli … Fantasy tastes of habaneros and honey, cinnamon and cloves, rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer.”

…but also the world-weary cynicism with which he brushed the dust off his favorite songs.

“Fantasy flies on the wings of Icarus, reality on Southwest Airlines. Why do our dreams become so much smaller when they finally come true?”

The Undying don’t do anything with their world that is a stage. Their true selves are nigh-zombified by an eternity spent imbibing evening’s shade. The doors of perception are open to them, and they’re just sitting there. The city of Qarth expresses the emptiness and listlessness of unlimited power at every turn. Like most fairy kingdoms, it’s disappeared so far up its own ethereal ass that none of its movers and shakers even enjoy the splendor they bled so many people dry to build. They are the Undying, not the living.

After Daenerys and her favorite dragon burn down the authorial panopticon, the warlocks in service to the Undying finally decide to use the power they keep insisting they possess. They set out after Dany with Dragonbinder and their faithful evening’s shade…only for their fledgling narrative be swallowed up, like so many before and since, in the magnetic maelstrom of the Crow’s Eye. Euron takes their ship, massacres their crew, and drinks far more shade of the evening than he should have. A life with neither limits nor consequences taught him precious little restraint. The warlocks next appear in “The Forsaken,” tossed into the hold of Silence to join Aeron, sans several limbs among them. Euron had forced them to eat one of their own, and laughed. “Men are meat.”

At the end of “The Forsaken,” he ties them along with priests he’s gathered from all the world’s religions to the prows of his ships. He reserves Aeron for the prow of Silence, tied up alongside Falia Flowers, a young woman Euron seduced and impregnated before cutting her tongue out. When we last see the Crow’s Eye in the story so far, he’s on the deck of Silence bedecked in a Valyrian steel suit of armor, something the audience didn’t even know existed in-universe until that moment. He wears it like a second skin, just another miracle. Euron’s forces are sailing into battle against the powerful Redwynes, neighbors to their recent victims and the most powerful naval force in Westeros. Having sent the Iron Fleet, cream of the pirate crop, off with Victarion to Slaver’s Bay, Euron doesn’t stand much of a chance of winning this battle. He’s not trying to. Both the magical suit of armor and the priests on the prows speak to Euron trying to channel immense power. He will annihilate both the Redwyne fleet and his own in a colossal blood sacrifice. Aeron Damphair’s last moments in this mortal vale will be spent praying in vain to his old god, only to see a new one walk out of the scarlet waves, powered in part by the king’s blood he pumped into poor Falia’s belly like Alien’s chestburster.

Unlike the Undying, Euron’s brand of postmodern supervillainy is active, aggressive. He walks fearless through the doors of perception; not content with seeing through every story, he will bring them all and in the darkness bind them. The Undying and their warlocks devoted their lives to shade of the evening, but for Euron it’s just yet another way to fly.

He offers it to Victarion at one point, but the latter promptly spits it out. Aeron has no such luxury in the heart of Silence; Euron forces it down his throat. He drinks full, and descends.

art by Malky Dungeon

“Your god will come for you tonight. Some god, at least.”

And when the Damphair slept, sagging in his chains, he heard the creak of a rusted hinge.

“Urri!” he cried. There is no hinge here, no door, no Urri. His brother Urrigon was long dead, yet there he stood. One arm was black and swollen, stinking with maggots, but he was still Urri, still a boy, no older than the day he died.

“You know what waits below the sea, brother?”

“The Drowned God,” Aeron said, “the watery halls.”

Urri shook his head. “Worms… worms await you, Aeron.”

When he laughed his face sloughed off and the priest saw that it was not Urri but Euron, the smiling eye hidden. He showed the world his blood eye now, dark and terrible. Clad head to heel in scale as dark as onyx, he sat upon a mound of blackened skulls as dwarfs capered round his feet and a forest burned behind him.

“The bleeding star bespoke the end,” he said to Aeron. “These are the last days, when the world shall be broken and remade. A new god shall be born from the graves and charnel pits.”

Then Euron lifted a great horn to his lips and blew, and dragons and krakens and sphinxes came at his command and bowed before him.

“Kneel, brother,” the Crow’s Eye commanded. “I am your king, I am your god. Worship me, and I will raise you up to be my priest.”

“Never. No godless man may sit the Seastone Chair!”

“Why would I want that hard black rock? Brother, look again and see where I am seated.”

Aeron Damphair looked. The mound of skulls was gone. Now it was metal underneath the Crow’s Eye: a great, tall, twisted seat of razor sharp iron, barbs and blades and broken swords, all dripping blood.

Impaled upon the longer spikes were the bodies of the gods. The Maiden was there and the Father and the Mother, the Warrior and Crone and Smith…even the Stranger. They hung side by side with all manner of queer foreign gods: the Great Shepherd and the Black Goat, three-headed Trios and the Pale Child Bakkalon, the Lord of Light and the butterfly god of Naath.

And there, swollen and green, half-devoured by crabs, the Drowned God festered with the rest, seawater still dripping from his hair.

The dreams were even worse the second time. He saw the longships of the Ironborn adrift and burning on a boiling blood-red sea. He saw his brother on the Iron Throne again, but Euron was no longer human. He seemed more squid than man, a monster fathered by a kraken of the deep, his face a mass of writhing tentacles. Beside him stood a shadow in woman’s form, long and tall and terrible, her hands alive with pale white fire. Dwarves capered for their amusement, male and female, naked and misshapen, locked in carnal embrace, biting and tearing at each other as Euron and his mate laughed and laughed and laughed…

Out of the blue, and into the black. In the privacy of a helpless man’s dreams, Euron sheds all skins and emerges, fangs glistening in the light of the bleeding star. Urrigon gives way to Euron as the joker yields to the reaper. The Crow’s Eye blazes balefully atop Barad-dur, but Martin is merely nodding to Tolkien one last time on his way down. The main reference points for these psychedelic-horror tableaux are darker and stranger. Lynch and Jodorowsky, Brueghel and Bosch, horror vacui and MK Ultra. Martin has said he doesn’t read manga nor watch anime, in which case he does an incredible impression of someone who does; the dream sequences in “The Forsaken” feel like a highlight reel culled from the most imaginatively unsettling images in both.

Euron’s own gnarled literary roots stand out more clearly with his smiling eye shut. He is Kundera’s vertigo, “the desire to fall.” He’s Pratchett’s Reacher Gilt; Pynchon’s Teutonic death’s-head Blicero; Lovecraft’s prying man, calling to the horrors beyond life’s edge.

He is, perhaps above all, Stephen King’s Randall Flagg. “As for the end of the universe, I say let it come, whether in fire, ice, or darkness.” The Walkin Dude is fueled by apocalypse, ever smiling upon his brutish followers until the time comes to feed on them. This description of him in The Stand easily could’ve been written about Euron and Dragonbinder at the kingsmoot:

When he walked into a meeting, the hysterical babble ceased—the backbiting, recriminations, accusations, the ideological rhetoric. For a moment there would be dead silence and they would start to turn to him and then turn away, as if he had come to them with some old and terrible engine of destruction cradled in his arms, something a thousand times worse than the plastic explosive made in the basement labs of renegade chemistry students or the black market arms obtained from some greedy army post supply sergeant. It seemed that he had come to them with a device gone rusty with blood and packed for centuries in the Cosmoline of screams but now ready again, carried to their meeting like some infernal gift, a birthday cake with nitroglycerine candles.

art by Mike Perkins

Varys the Spider plans to cut through the webs with a single note (his “perfect prince,” who like Euron is not as he appears) to resolve all discordance, like the civilization-crashing piano chord that concludes “A Day in the Life.” Consider Euron to be the inverse: the abyssal hush cradling that piano chord, brought to life and hunting your children. A song none of us can sing, our mouths stitched shut as we’re nailed to his prow, made to bear witness. How long do we have to look? As long as it pleases him.

But rewind to just before the bad trip kicks in. Aeron spits evening’s shade in his tormentor’s face, and what follows is perhaps the most revealing Euron moment of all:

The spittle struck his brother’s cheek and hung there, blue-black, glistening. Euron flicked it off his face with a forefinger, then licked the finger clean.

Euron is an addict, hooked on power. He got an overdose of the feeling he could fly as a child, and has been chasing that high ever since. Blood magic, sorcerous artifacts, psychedelic drugs, the rape and murder of his own brothers…it doesn’t matter to him where it comes from so long as it comes, and while that’s terrifying, it’s also pathetic. Nothing means anything to him except the pure rush of power, so when that power is challenged (as when the Reader questions his story), he falls apart to reveal that there’s nothing inside. There is no endgame. He’ll just never, ever stop.

Euron works best taken in context with characters like Daenerys who dance with the devil in the name of more relatable ends. Euron represents the dead end result of that process, when you’ve lost everything that connected you to humanity. All that’s left is the hunger for power, more and more, until your fire burns out and you’re left alone with your sins. “I tried to grasp a star, overreached, and fell.”

In the meantime…once he gets past the Redwynes, Euron will need a base of operations worthy of his ambitions. By the end of A Feast for Crows, he has one in mind.

The Redwyne Straits were swarming with longships, as they had been warned in Tyrosh. With the main strength of the Arbor’s fleet on the far side of Westeros, the ironmen had sacked Ryamsport and taken Vinetown and Starfish Harbor for their own, using them as bases to prey on shipping bound for Oldtown.

The ironmen had penetrated even to the sheltered waters of Whispering Sound. Come morning, as the Cinnamon Wind continued on toward Oldtown, she began to bump up against corpses drifting down to the sea. Some of the bodies carried complements of crows, who rose into the air complaining noisily when the swan ship disturbed their grotesquely swollen rafts. Scorched fields and burned villages appeared on the banks, and the shallows and sandbars were strewn with shattered ships. Merchanters and fishing boats were the most common, but they saw abandoned longships too, and the wreckage of two big dromonds. One had been burned down to the waterline, whilst the other had a gaping splintered hole in her side where her hull had been rammed. “Battle here,” said Xhondo. “Not so long.”

“Who would be so mad as to raid this close to Oldtown?”

Xhondo pointed at a half-sunken longship in the shallows. The remnants of a banner drooped from her stern, smoke-stained and ragged. The charge was one Sam had never seen before: a red eye with a black pupil, beneath a black iron crown supported by two crows. “Whose banner is that?” Sam asked. Xhondo only shrugged.

“My apologies,” the captain said when his inspection was complete. “It grieves me that honest men must suffer such discourtesy, but sooner that than ironmen in Oldtown. Only a fortnight ago some of those bloody bastards captured a Tyroshi merchantman in the straits. They killed her crew, donned their clothes, and used the dyes they found to color their whiskers half a hundred colors. Once inside the walls they meant to set the port ablaze and open a gate from within whilst we fought the fire. Might have worked, but they ran afoul of the Lady of the Tower, and her oarsmaster has a Tyroshi wife. When he saw all the green and purple beards he hailed them in the tongue of Tyrosh, and not one of them had the words to hail him back.”

Sam was aghast. “They cannot mean to raid Oldtown.”

The captain of the Huntress gave him a curious look. “These are no mere reavers. The ironmen have always raided where they could. They would strike sudden from the sea, carry off some gold and girls, and sail away, but there were seldom more than one or two longships, and never more than half a dozen. Hundreds of their ships afflict us now, sailing out of the Shield Islands and some of the rocks around the Arbor. They have taken Stonecrab Cay, the Isle of Pigs, and the Mermaid’s Palace, and there are other nests on Horseshoe Rock and Bastard’s Cradle. Without Lord Redwyne’s fleet, we lack the ships to come to grips with them.”

art by Juan Carlos Barquet

Oldtown is old. Very old. Too old. It shows smiling eyes to the world, the Citadel and the Starry Sept, the epicenters of secular education and religious faith coexisting comfortably. But if you follow the stories back, Call of C’thulhu style, you find that city’s roots are tentacled.

How old is Oldtown, truly? Many a maester has pondered that question, but we simply do not know. The origins of the city are lost in the mists of time and clouded by legend. Some ignorant septons claim that the Seven themselves laid out its boundaries, other men that dragons once roosted on the Battle Isle until the first Hightower put an end to them. Many smallfolk believe the Hightower itself simply appeared one day. The full and true history of the founding of Oldtown will likely never be known.We can state with certainty, however, that men have lived at the mouth of the Honeywine since the Dawn Age. The oldest runic records confirm this, as do certain fragmentary accounts that have come down to us from maesters who lived amongst the children of the forest. One such, Maester Jellicoe, suggests that the settlement at the top of Whispering Sound began as a trading post, where ships from Valyria, Old Ghis, and the Summer Isles put in to replenish their provisions, make repairs, and barter with the elder races, and that seems as likely a supposition as any.

Yet mysteries remain. The stony island where the Hightower stands is known as Battle Isle even in our oldest records, but why? What battle was fought there? When? Between which lords, which kings, which races? Even the singers are largely silent on these matters. Even more enigmatic to scholars and historians is the great square fortress of black stone that dominates that isle. For most of recorded history, this monumental edifice has served as the foundation and lowest level of the Hightower, yet we know for a certainty that it predates the upper levels of the tower by thousands of years.