Tags

himalaya, Nanda Devi, Nanda Devi Sanctuary, Nanda Kot, Plutonium device, Robert Schaller, Spy in the Himalaya

The Goddess looms in his memory. She is both muse and Mata Hari, and for a brief moment nearly half a century ago, she was his.

But Nanda Devi, the Himalayan peak known as the Goddess for her beauty and her wrath, is a fickle mistress. She has stolen other men’s lives and sent a woman to her grave. She has claimed a piece of Robert Schaller as well.

In 1965, Schaller was part of an American spy team that tried to place a nuclear-powered surveillance device on top of Nanda Devi, one of the highest mountains in the world.

That mission was a spectacular failure. The device and its nuclear core vanished along with, or so the CIA hoped, any news about it.

Now, Schaller’s participation in that covert expedition has sent him on a new, perhaps equally remote quest. He wants to reclaim something else he lost on Nanda Devi — something now in a place even less accessible than the ice vault of the mountain.

For Schaller, there is no half-life for regret.

In 1965, Robert Schaller was a golden boy Harvard grad who could run a mile in a second shy of four minutes. Recently arrived from the East Coast, he had come to Seattle to start his medical residency at the University of Washington. Blue-eyed and engaging, Schaller had a wife, two young children and an addiction the day the CIA came calling.

Schaller is 72 now, his surgeon’s hands crippled by arthritis, but two moments sear like snow blindness in his memory — the day he got hooked on mountain climbing and the day the government took advantage of that.

Schaller had been a climbing fanatic since the instant he had arrived in Seattle in 1960. He had driven his beat-up Mercury cross-country to start his residency, and it broke down, still packed with all his belongings, on what was then a two-lane highway near the Issaquah turnoff. The car gasped to a stop at precisely the gap in the view where Mount Rainier presided over the horizon. Stranded, the Detroit-raised Schaller stared at the mountain for several hours.

“It blew me away,” he said.

After that, he spent every available weekend learning to climb, testing his endurance equally against the rock and his long hours on call as a young surgeon.

Schaller had just returned from climbing Mount McKinley when the CIA reached out.

The front desk at University Hospital paged Schaller out of rounds in the middle of a spring day in 1965. He hurried to the lobby, his imposing frame — 6 feet 3 inches — still clad in the short white lab coat, white pants and the white shoes typical of interns of that era. The man in the entrance foyer wore a trench coat and dark glasses.

The agent sneaked open his coat, and Schaller glimpsed an airline ticket.

“How would you like to go to the Himalayas?” the agent asked.

Schaller couldn’t say yes fast enough.

The government was looking for a physician with some interest in electronics who also had a background in high-altitude medicine for a classified mission to place a “listening device” somewhere on the Roof of the World.

“There weren’t very many IBM cards that dropped out with those qualifications,” Schaller said.

Schaller had an additional qualification that appealed to the CIA — he was a patriot.

A few months earlier, the Chinese government had set off a nuclear test, triggering an anxiety attack throughout the West.

“They waved the American flag at me,” he said “This was a unique opportunity to do something really exciting and serve my country.”

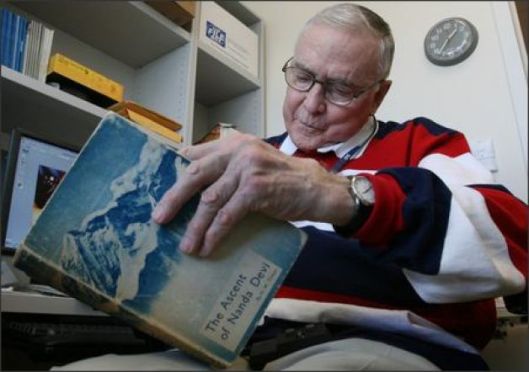

Robert Schaller, a former pediatric surgeon who still teaches at Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center in Seattle, looks over a copy of “The Ascent of Nanda Devi.” In 1965, Schaller tried to scale the peak to install a listening device that never made it to the top.

(Photo Credit: Grant M. Haller/Seattle Post-Intelligencer / SL)

Spies in the Sanctuary

In the 1960s, the Himalayas were still a climber’s Shangri-La, a wild, legend-making place free of the commerce and celebrity that would characterize climbing in the late 20th century.

The last-wilderness aspect of it appealed to Schaller.

“We had to really struggle just to get to the mountains,” Schaller said. “We were very much out there on our own. We didn’t have the help of modern telecommunications, or weather reports. Porters were hard to come by.”

Nanda Devi is one of the 25 highest peaks in the world — the second-highest in India — and stands at the heart of a vortex of stunning crests that form a geographical fortress known as the Sanctuary. The ice fields of the Sanctuary feed the headwaters of the Ganges, which in turn sustains one of the world’s densest population bases. The Ganges is also considered sacred in the Hindu tradition. A sip of its waters with your last breath is said to guarantee the soul’s passage to heaven.

Bathing in its waters will cleanse the soul of sin.

No recorded expedition had breached the Sanctuary until 1934, and Nanda Devi, rising to more than 25,000 feet, wasn’t climbed until 1936.

Years later, Nanda Devi would earn her reputation as an angry goddess when Devi Unsoeld, daughter of famed Washington climber Willi Unsoeld, died while climbing her namesake.

What captivated the U.S. government about Nanda Devi in 1964, however, was not the grail of its summit, nor its mystic powers, but its unobstructed view over Tibet and beyond to the Xinjiang province, site of the Chinese missile-testing ranges.

In October 1964, the Chinese government had detonated its first nuclear test near Lop Nor. That combined with its burgeoning missile program worried the U.S. and India sufficiently for the two governments to hatch what even at the time must have seemed a 007-esque scheme. With the American fledging satellite system unlikely to be able to track the Chinese tests, they needed a different vantage point.

Schaller and a team of elite American and Indian climbers were to scale Nanda Devi and secure an instrument, powered by a plutonium generator. The device would intercept and transmit radio signals from the Chinese missile tests. The plutonium mixture would generate enough heat to make the electricity needed to power the transceiver, making the equipment self-sustaining in a hostile environment, a strategy since deployed in space as well.

It was a seemingly brilliant plan that hinged on one task — getting such a device planted atop one of the most unforgiving mountains in the world.

Lessons in the trade

The government dangled $1,000 a month in front of Schaller for his participation.

“That was a lot of money then,” he said.

But in the months after Schaller’s first meeting with the federal agent, he would begin to understand the cost of his participation. For months at a time, he would leave his family for training in tradecraft.

“It was very cloak-and-dagger,” Schaller recalls. “We would go to a place, be blindfolded and led into a canvas tunnel to an airplane with blacked-out windows.”

He guessed some of his fellow mission specialists were college professors because of their nuclear knowledge. Some also were renowned alpinists, including famed big-wall climber Tom Frost, who made history with his Yosemite climbs in the early 1960s.

Frost, a friend of Schaller’s, continues to honor his oath of secrecy, although both he and Schaller were named by Indian expedition leader M.S. Kohli and author Kenneth Conboy in their book, “Spies in the Himalayas,” and later by Pete Takeda in his book “An Eye at the Top of the World.”

“I can’t talk about that,” Frost said recently when given the opportunity once again to field questions about the missions.

But he did say Schaller was a good guy to climb with.

“We’ve spent some time together,” Frost said. “He has a real passion, a love for climbing and he does it well. He’s a good companion. He’s the kind of person you like to hang out with, particularly if you’re in a tough spot.”

“Whatever Rob says,” he said, “you can take that to the bank.”

Kholi, the Indian expedition leader, was a noted climber as well, having just put nine climbers on top of Everest in 1965.

The Americans operated with pseudonyms. “Mine was of someone who was dead — Norris P. Vizcaino,” Schaller said. “I never did find out who he was.”

The team flew to undisclosed locations. “We learned to blow up things using C3 and C4 (plastic explosives),” he said. “We jumped out of helicopters.”

The training missions lasted two to three weeks. “I couldn’t tell my wife or family,” he said.

That was the beginning of the secret keeping.

Disappearing

There would be a half-dozen missions in all over a period of three years.

Retired surgeon Tom King, who was a young resident alongside Schaller in the 1960s, recalls how his fellow doctor would just disappear.

“He would come back and have lost weight,” he said. “One time he came back with a broken leg. We all wondered what he was doing. But he would never say anything about it.”

His chief of staff, Dr. K. Alvin Merendino, now in his 90s, also confirmed granting Schaller multiple absences.

Schaller’s cover, if asked, was that he was training as a scientist-astronaut, and in some ways, the operation was as complex as putting a man in space.

According to Takeda, who spent years researching the history of the spy mission, only a half-dozen climbers had stood on the summit, and only three had survived to talk about it.

Schaller faced his own personal hurdles as he prepared in the spring and summer of 1965. Training injuries threatened to keep him off the mountain, grounding him from a training climb on Mount McKinley. At another point he got violently ill with typhoid fever and was forced off the initial attempt on Nanda Devi to recuperate in Delhi.

If he worried about his body breaking down, though, he kept it to himself and retained his focus on gritting his way to the Himalayas. The government’s agenda may have been a secret, but Schaller had a mission of his own.

The weather turns

In the fall of 1965, a year after the first Chinese nuclear test, the assembled climbers made their first push to put the spy device on top of Nanda Devi. About a dozen climbers and Sherpas portaged the equipment in pieces up the knife-edge route toward the summit.

The generator, which weighed about 40 pounds, held at least a half-dozen cells — each about the size of a cigar — containing an alloy of plutonium 238 and plutonium 239.

It was the potent combination of the two that made the device both hardy and heat-generating, so warm that the Sherpas would cozy up to it at night, Schaller said.

Just as the team reached Camp 1V, the last camp before the peak, however, a blizzard blew up and forced them to abandon the summit ascent. With no choice but to turn back, Kohli made a fateful decision — to lash the contraption to a ledge of rocks and leave it behind to avoid having to carry it a second time up the mountain.

The plan was to return in the spring climbing season to finish the job, Schaller said.

Throughout his training, Schaller had tried not to think about potential radiation damage in personal terms, though handling the warm cells made him nervous. With the equipment now at the mercy of the mountain, he remembers having qualms on a larger scale.

“I was very much against leaving the device,” he said.

A shocking discovery

In the spring of 1966, Schaller and the team returned to Nanda Devi with the goal of packing the equipment the rest of the way to the top. When the climbers arrived at the location where they had left the instrument, however, the entire rock ledge was wiped away, sheared off by a huge avalanche.

“The generator was completely gone,” Schaller said. “It caused great distress — a nuclear-powered device lost on a glacier on Nanda Devi.”

There were two concerns. The first was that the technology might fall into the wrong hands. The second, perhaps more ominous, was that the radioactive core might melt its way through the mountain’s glacier and into the headwaters of the Ganges.

In his book, Takeda estimates the amount of plutonium at 4 pounds — enough, he writes, to potentially threaten the lives of millions of Indians if released into the water.

The plutonium fuel cells had been rigorously tested. Schaller himself had helped drop them out of airplanes from 10,000 feet onto granite.

“They were known to be sturdy,” he said. “It’s hard to imagine how they could ever be destroyed.”

But if the fuel cells burned their way to bedrock, could the massive tonnage of the glacier, grinding away for decades, or centuries, destroy the core and release the plutonium to the environment?

No one can say.

This month, however, a potential clue emerged. In 2005, Takeda took a sample of sediment from waters in the Sanctuary. Recent tests on that coarse sample show the likely presence of plutonium 239, an isotope that does not occur in nature.

Stealing the instrument was, perhaps, the Goddess’ way of getting even, Takeda said in an interview between climbs from his base in Boulder.

“They had brought poison to her flanks, and she responds by batting it down and burying it where we can’t find it,” he said. “It was like a hand slap — a reminder that though we had this knowledge, control of it was out of our grasp.”

After numerous searches were unable to locate the lost device on Nanda Devi, Robert Schaller climbed in the Himalayas again to install a similar device on the neighboring peak of Nanda Kot. The device, like the lost one, contains plutonium fuel cells to power its transceiver.

(Photo Courtesy Of Robert T. Schaller, M.D. / SL)

At the top of the world

The loss of the generator triggered fallout in the Indian government, according to Kohli’s book, and a massive joint effort to save face and recover the device. Between 1966 and 1968, the CIA flew stripped-down Husky helicopters through the thin air of the Sanctuary, scouring the side of Nanda Devi where the device was lost. They photographed each grid, and sent climbers in to search for debris with Geiger counters.

The loss also spawned a second mission — successful this time — to place a similar device on Nanda Kot, a neighboring peak.

For Schaller, the recovery effort and Nanda Kot expedition were bonuses. They gave him more time to climb in the Himalayas. He had been warned not to climb when he was off duty, but he couldn’t resist the mountains’ siren call.

“I climbed everything in sight on my off days,” he said.

He carried his small half-frame Olympus camera and a journal with him, recording his personal feelings and logging notes about the climbs, a personal record of his life at the top of the world.

One pre-dawn in September 1966, Schaller and his tent-mate Frost stole away from the high camp on Nanda Devi and started toward the summit. At their first rest point, Frost abandoned the ascent. He wasn’t feeling well, Schaller said.

But Schaller pressed on.

“The weather was perfect,” he said. It was a windless, dark-blue sky day and the sun was shining. He knew this was his shot.

Crampons on, he slogged for hours toward the peak until he reached what looked like the final cliff between himself and the summit. The route should have taken him around the cliff and to the top, but he thought he would forge a shortcut.

“Altitude plays tricks on your mind,” he said. About 40 feet up the rock face, breathless and dizzy, he toppled backward. He lay in the snow, regrouping and feeling for broken bones.

“I was lucky,” he said. “I wasn’t killed.”

After 40 minutes of rest, he followed the known route, and finally, after all the months and failed starts and doubts, he reached it.

“I was laughing. I was exhilarated, and exhausted,” he said. “It was spectacular to be up there — to look out at the world around me.”

He snapped a photo of himself at the top.

Over the next several decades, Schaller would climb more than a dozen times in the Himalayas — scaling the Northeast Ridge of K2 among others. But that one morning on Nanda Devi stood out above all others as his personal zenith.

“This was long before (Reinhold) Messner had soloed Everest,” said Jim McCarthy, a retired trial lawyer from Jackson Hole who climbed alongside Schaller for the CIA. “Schaller’s ascent might well have been the singular achievement of the ’60s — if it had been known.”

The climbers never did find the instrument lost on Nanda Devi.

Toward the end of the final Himalayan expedition, the federal operative on the team asked to see Schaller’s journals and his film. He told Schaller he thought it would help him file his report to headquarters. Schaller, who to this day is an eager teacher, shared it readily, assuming he would get them right back.

When he asked for his materials later, however, the agent refused.

Schaller realized that he had just made what Kohli, Takeda and others have since called the greatest alpine climbing feat accomplished by an American up to that time.

But it was Schaller’s word, and the mountain’s secret.

He had no proof.

The cost of secrets

Schaller received an Intelligence Medal of Merit for his contributions to the espionage missions. Two agents came to his house and draped a silvery medal on ribbons around his neck. Then they took it away. He presumes it is locked in a vault at the CIA’s Langley headquarters along with myriad other artifacts that officially don’t exist.

Along with his journals and photographs.

At home, his absences exacted a different price. His wife, Jane, was left to handle two young children and a demanding job on her own. The two had met in medical school, where she was one of only four female students. They were a handsome, accomplished couple — and had fallen hard in love.

“We eloped after two dates,” he said.

Though she also loved the mountains and climbed Mount Rainier with him in their early years of marriage, she didn’t love the obsession, or the risk, their son said. And the unexplained absences frayed their connection, until it finally broke.

“He couldn’t tell her where he was going,” said Robert Schaller, the couple’s first-born, who was only 2 years old when his father began disappearing. Over time, his father adapted to his clandestine way of life, but his mother never could.

“The culture of secrecy itself became for my father a valid way of conducting his affairs,” said Schaller, now a filmmaker, who is attempting to document his father’s CIA life. The senior Schaller eventually left the family in a bitter parting after 13 years of marriage.

He married twice more and has seven children. But he has just begun assessing the cost of his secret life.

“It had a lot to do with the end of my first marriage,” he said. “I never should have left my first wife.”

A personal wilderness

Today, Schaller is a man reckoning with legacies.

After his government service, and three years as an Army doctor, he settled into a long, prestigious surgical career in Seattle that included a wide range of operations, from separating conjoined twins to organ repairs in the tiniest preemies, work he loved.

“I would buy tickets to do this job,” he said.

“He was the go-to pediatric surgeon in Seattle,” said Dr. Bob Sawin, current chief of surgery at Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center. “At one point, he personally did more surgeries than all the other pediatric surgeons combined. He has always been very, very busy.”

He was also a meticulous documentarian, compiling thousands of slides of his surgeries over the years, an effort Sawin called unparalleled.

They’ve piled up in boxes at the Bellevue house where he now lives alone, separated from his third wife, wishing for a reconciliation and struggling with a failing body.

He regrets he will never be able to show his younger children the mountains in the way he once knew them.

He feels he has paid for his secrets. “I gave (the government) quite a lot of my life,” he said.

A self-described workaholic, he believes his single-mindedness in pursuit of his goals — both in climbing and in medicine — cost him his dearest relationships, and his health.

He has had both knees replaced, and his spine fused. He is 4 inches shorter than he was as a young man. He faces the likelihood of more surgery on his hands. He gave up operating about three years ago. His solace now is teaching.

He still lectures once a week at Children’s and sprinkles his talks with slides of mountains he has climbed.

On a recent weekday, Schaller, wearing a bulky neck brace, hunched over the computer in his cramped hospital office. He fiddled with the color on one of his slides, trying for a digital match. His hope is to turn his personal archive into a working atlas for medical educators.

Schaller seems reassured, if somewhat overwhelmed, to have this project. It’s evidence of his years of work as a doctor.

“This will be my legacy,” he said.

About his other legacy, he is less certain. He regrets the CIA team was never able to find the remains of the device and recover the plutonium. Although he believes a serious environmental threat is only a remote possibility because of the vast dilution any leak would face, he subscribes to the mountaineer’s ethic to leave nothing behind.

Abandoning plutonium on the mountain was a violation of its sacred trust, he said.

And a violation, perhaps, of another oath he took: First, do no harm.

He has made an amend of sorts. In 1968, he testified before Congress in support of establishing the North Cascades National Park.

“Wilderness has intrinsic value that cannot be priced,” he testified. “What would you pay for a view of snow-sparkling, glaciated mountain peaks? … Once this wilderness is lost, it can never be reclaimed.”

His testimony, along with that of others, helped secure the park’s wilderness status.

An unclaimed past

A final historic legacy still eludes him — his unverified first solo ascent of Nanda Devi.

In 2005, after reports had surfaced in Kohli’s book and in magazine articles about U.S. climber-spies in the Himalayas, Schaller began another quest — to reclaim his records from those secret climbs.

Three times he appealed to the government through Freedom of Information Requests asking for his personal diary and photographs from the Nanda Devi and Nanda Kot climbs.

Each time he was denied.

“The CIA can neither confirm nor deny the existence or non-existence of records responsive to your request,” the letters said. “Such information — unless it has been officially acknowledged — would be classified for reasons of national security … . The fact of the existence or non-existence of such records would also relate directly to information concerning intelligence sources and methods.”

The CIA made a similar denial when the Seattle P-I made a request for records of the expedition.

Schaller also appealed to Sens. Maria Cantwell and Patty Murray, as well as Rep. Dave Reichert, but has gotten nowhere.

Under a new law, the government automatically declassifies documents more than 25 years old, unless a specific exemption is sought.

“I feel betrayed by this process,” he said. “I can’t see how my personal diaries and photographs would be of any risk to national security, and they certainly don’t reveal anything about the operations of the CIA”

Schaller’s agitation brims, and he turns from his computer. He gazes out the window toward the Olympic Mountains in the distance.

“Look,” he says. “The Brothers are out.”

The view makes him wistful. He is a man facing the most unassailable peak of all — his mortality.

There is a piece of his life likely boxed and forgotten in some deep CIA archive.

He just wants it back.

* * * * *

Article by Carol Smith (P-I reporter)

Published Sunday, March 25, 2007

Link to the source article

Reblogged this on Outdoors India and commented:

CIA, espionage, spies, mountaineering, nuclear devices. This could very well be the ingredients for a Hollywood script. But the fact remains this is as real as it was. The story unfolds atop one of natures most revered peaks, The Nanda Devi, surrounded by stunning crests that form a geographical fortress called The Nanda Devi Sanctuary. It was a CIA mission to establish a nuclear powered spying device atop Nanda Devi to eavesdrop on China. The device was lost to natures fury. Perhaps it was the mountain goddess claiming it as her own. From then on, the peak was closed for civilian expeditions. While for decades it has always been a mystery as to why the peak was closed for expeditions, recent revelations have been made by those who were part of the climbing team. This is the story of a CIA spy entrusted with the mission of implanting that device. Robert Schaller talks about what went wrong on the expedition, and not just that. He also talks about a record breaking alpine feat, the proof of which perhaps lies in an old forgotten agency cabinet somewhere…

With due respect to the passion and love of the climbers of the secret mission,it was probably some other aspect which made them agree to such an insane and absurd mission. Had it been genuine love for the Himalayas, no climber would have succumbed to such a heinous mission(i.e. planting poison on the top of one of the world’s most beautiful peaks). Nanda Devi lived to her cult image of angry Goddess and did give a tight slap on the attitude of Indian govt. and its bumptious bureaucrats.

Also, many interested people (not all) are of the mistaken opinion regarding the reasons of the closure of the sanctuary. The mission was carried out in 1965 and the sanctuary was declared closed in 1982 after the promotion of the area as a National Park and granting of World Heritage status to the park. The spectacular sanctuary then had lured a lot of foreign and Indian mountain enthusiasts to explore or scale Nanda Devi and its neighboring peaks just like the Everest region in Nepal. This had caused irreparable loss of biodiversity to the surroundings as large swathes of birch forests and other species were cleared for logistical and fuel purposes of the visiting teams for whom the success of their respective expeditions was more important than the colossal ecological damage their expeditions were causing to such a pristine area. Thankfully some sane bureaucracy and honest efforts of a number of ecologists brought an end to this unending drama of destruction in 1982. This has been well reported in “The Nanda Devi Affair” by Bill Aitken.

Today, the passage across the Rishi Ganga gorge is banned for civilians and the region has somewhat regained its past glory. Same action needs to be emulated for all the ecologically sensitive areas in the Himalayas since man’s greed for exploration should rank last in the priority list of the administration.