A horse named Gizmondo: The inside story of the world's greatest failed console

From the archive: A look at one of gaming's most spectacular failures.

Every Sunday we bring you a selection from our archives, giving you the chance to discover something for the first time or maybe to become reacquainted. This week we present Ellie Gibson's fascinating insight into the downfall of Gizmondo, perhaps the gaming industry's most spectacular failure. This feature was originally published in August 2012.

"That was the least expensive thing, I think, of all of it," says Carl Freer.

What a lot of it there was. Luxury yachts and Rolex watches. Ferraris, modelling agencies and million-pound salaries. A launch party headlined by Sting. A £2 million investment in a development studio that never produced a single game.

Freer isn't talking about any of that. He's talking about a racehorse. Its name was Gizmondo.

"Actually, the horse won," he says. "It made money. Can you believe that?"

---

"The Gizmondo is the most advanced handheld gaming console you've ever seen. On steroids."

Carl Freer, MCV, August 2004

It's often been said that the story of the Gizmondo would make a great movie. In fact, it would make a terrible movie, one with an implausible plot and a predictable ending, probably starring Stephen Baldwin.

Here is that story, in brief: back in March 2005, Tiger Telematics launched a handheld console called the Gizmondo. It was supposed to run great games, play videos, send text messages, power GPS apps and more. A raft of wealthy investors were on board, along with many major games publishers and high street retailers.

Less than a year later, Tiger Telematics went bankrupt. The financial filings were a mess of huge debts, weird share deals and unresolved lawsuits. The company's total losses stood at £189 million. The Gizmondo went down in history as the worst-selling handheld of all time.

Here's the sub-plot: in February 2006, a Ferrari Enzo travelling at 162 miles per hour crashed on a Californian highway. Gizmondo executive Stefan Eriksson, who had previous convictions for involvement with the Swedish mafia, was found at the scene. Eriksson claimed the driver, a man named Dietrich, had done a runner. Police alleged the Ferrari had been illegally imported. Eriksson served two years in prison. Dietrich was never found.

What follows is not meant to be a comprehensive account of the Gizmondo saga or an exposé of Tiger Telematics' financial machinations. Those have already been written (notably by Randall Sullivan for Wired and Everything2's archiewood). This is the story of the Gizmondo, as told by some of the people who were there.

---

"Affordably priced, pocket-sized, and seriously sexy."

Steve Carroll, MCV, August 2004

Carl Freer was there from the very beginning. But, as he explains in our interview, when he founded Tiger Telematics back in 2002, he had no intention of making a games console. The big idea was to produce a device which could track the whereabouts of children using GPS technology. "Do you remember the Soham murders? Terrible," Freer says. "We were all parents and we were talking about the issues around that. We started looking at doing a child tracker."

The problem, Freer's team realised, would be getting children to carry such a device around with them. "So we thought, how about we make it more fun? What if we put in a gaming interface?"

The task of incorporating this feature fell to Steve Carroll, Gizmondo's chief technical officer. "My job was to execute Freer's design concepts through our channels of developers," he explains. The end result was a machine built around the Windows CE.net platform, with a Samsung processor and an NVIDIA graphics accelerator. It was a portable, multi-functional communications and entertainment device. According to Carroll, it was ahead of its time in more ways than one.

"Freer slammed a sheet of paper on my desk one day and said, 'I have an idea' - a term which was to become very familiar to me. He said, 'When we launch, I want to open an online app store. Customers can come and download apps and games, we will provide customer support... And we are going to have young guys dressed in trendy clothes, connecting with our clients...'

"Does this sound familiar? You would think we were copying a very well known brand. The only thing is, he told me that in 2004."

It comes as no surprise to hear the Gizmondo hailed as a cutting-edge technological marvel by the people who invented the Gizmondo. But, with all that happened after the machine's launch, it's easy to forget that Freer and Carroll weren't the only ones who had high hopes for it.

---

"We estimate [Gizmondo] could garner as much as 10 per cent of the handheld gaming market, making it the third serious mobile platform development option in the market with the Nintendo DS and Sony PSP."

Terranova Institutional Equity Research report, January 2005

---

"The word 'wow' will suddenly become imbued with new meaning."

Gizmondo Launch Guide, MCV, August 2004

Plenty of analysts and journalists were impressed with the Gizmondo's capabilities. In Eurogamer's own review, I described it as "a neat little machine that has enough going for it to make a purchase worthy of consideration". (Which was pretty generous of me, considering the same article mentions poor movie playback, fiddly file transfers, painful text messaging and the GPS being broken. I was very young.)

But the real secret to Gizmondo's short-lived success lay in Freer's ability to convince games industry professionals, retailers and even rock stars to get on board. People like consultants Will and Louise (not their real names), who were hired to work on Gizmondo from the start. They agreed to be interviewed only under condition of anonymity.

"If I came to you and said, 'Look, I've got this thing and I'm going to launch it,' not in a million years would any part of your brain think it was a massive scam," says Louise. "You'd just take it at face value, as human beings do."

Will's first impression of the Gizmondo was that it was the industry's best-kept secret. "We looked at it through gamers' eyes, and what they were trying to do was amazing," he says. "They were proposing the first true mobile handheld. It was basically the iPhone of its day."

What really convinced Will to get on board, however, was the sheer force of Freer's personality. "He was an incredible individual. If you were interviewed for his start-up company you'd want to be part of it, regardless of what it was. If you imagine us normal people are like little dinghies, Carl Freer is a big f***-off yacht. Wherever he went, you just got caught in his wake."

Louise added: "Freer is so clever and brilliant, he could go and run Microsoft."

---

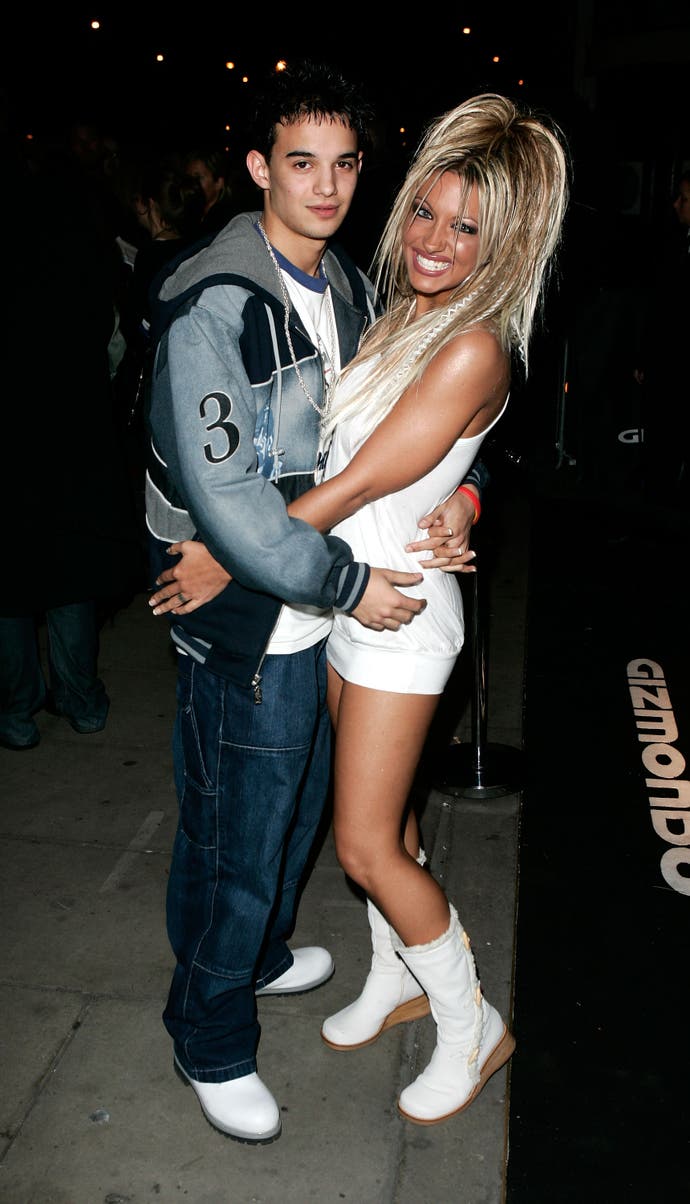

"It was anything but a boys-and-their-toys event at the launch party for new computer console Gizmondo. Among the glamorous girls who turned up were Rachel Hunter and Girls Aloud stars Kimberley Walsh and Cheryl Tweedy."

'A Show-Giz Party', The Sun, March 2005

But Freer didn't want to work for anyone else. He wanted to run his own company and sell his own console, and he wanted everyone to know about it. So for the Gizmondo's launch, on 19 March 2005, he threw the biggest party the games industry had ever seen.

Held at the swish Park Lane Hotel, it was attended by a host of celebrities including Lennox Lewis, Jodie Kidd and Rachel Stevens. That might not sound like the most star-studded roster, but it's worth remembering that back then the typical celebrity guest list for a games industry party was comprised of Ralf Little and a couple of people off Hollyoaks.

The event was hosted by Dannii Minogue and comedian Tom Green. (Will remembers Green coming onto the stage with a Gizmondo, declaring it to be indestructible and then throwing it onto the ground, where it shattered into hundreds of pieces: "He stood there looking awkward while Dannii Minogue went over to pick it up.")

The real stars were the live acts. Busta Rhymes, Pharrell Williams and Jamiroquai all put in an appearance. Topping the bill was Sting, who put in a crowd-pleasing performance, as Louise recalls: "He did one song which was like, 'Ooh, yeah, the rainforest...' And everyone was like, 'F*** off, Sting.' Then he did five Police songs and everyone went, 'Wow.'"

From the outside, Will reckoned the party looked like it cost around £3 million. But in reality, it didn't cost anything near that figure. "Gizmondo were taking on talent the same way they were working with business, which was with a share deal," he claimed. "People were seeing a massive uplift in the share price, so they were willing to take hundreds of thousands of shares in place of cash."

Louise backs up Will's recollection. She says the expenses paid in shares included Sting's fee, which she put at around £300,000.

When asked about all this in our interview, Freer says he can't remember how much the party cost, or whether share deals were involved. "Like any entrepreneur, if I have an icon I want to get involved with my company, the first thing I do is make sure that artist feels they have ownership in what they're representing," he says. "So we were probably quick to offer that, but I'm not sure what happened in the end."

Steve Carroll doesn't think the event was that much of a big deal. "There were no flash parties," he says. "Just a strategic launch event which was agreed by the Board, discussed extensively with stakeholders and successful in line with expectations."

This isn't quite the position Freer takes. "Shock and awe, that's what a launch is about," he says. But was it really necessary to throw such an extravagant bash? "Well, you still remember it, so we must have done our job."

---

"It's all new and clean. Just like the Apple Store, only not selling anything you aspire to own. It'll still be new and clean when they board it up in a couple of months, too!"

'Visiting the Gizmondo Shop!', UK: Resistance, April 2005

Along with the launch party came the grand opening of the flagship Gizmondo store. It was located in the heart of London at 175 Regent Street, prime retail turf. "I think we blocked off half the street that day," says Freer. "We took a lot of customers from Hamleys. That was fun."

While the party had been about getting the media's attention, the shop was a statement about where Gizmondo saw itself in the marketplace. Back then (and still today) there was no such thing as a retail space devoted exclusively to selling a games console. Even the Apple Store had only been open for less than six months.

Tiger Telematics was squaring up to the big boys. Freer confirmed this in a letter to company employees, dated 12th April 2005: "We're now directly in Sony and Nintendo's line of sight, and it's up to each and every one of us to do our part to expand the foothold we already have in the market."

Looking back, Freer says there was no grand plan to topple the reigning console manufacturers. "We never thought we would take them down. We just felt there was a market big enough to provide a little variety. Go down the high street and there are more than two types of restaurant, right?"

That's not the impression that was always given at the time. Will remembers Tiger Telematics acquiring a decommissioned Tomahawk missile. The Nintendo DS and Sony PSP logos were painted on the nose cone, while the shaft bore the Gizmondo name.

The missile was placed outside the firm's head office, which was located next to Farnborough air base in Hampshire. According to Will, "It took approximately 17 minutes for three Humvees loaded with troops to deploy around it, saying, 'Why have you got a live nuclear warhead next to our air base?'"

Back at the Gizmondo store, other problems were starting to arise. Technical difficulties were making it tough for staff to show off all the machine's features. "Every time they did a demo of the GPS, they had to walk out of the store and hold the machine up high for about half an hour while the customer was waiting," says Will. "So yeah, that was a bit of a difficult one."

I went to the shop to pick up a Gizmondo for my review. I remember walking down Oxford Street, trying to get the GPS to work, and failing.

"Oh yeah?" says Freer, when I tell him this. "There were problems with the first batch of units. Overall they worked fine, but you're always going to have bugs. The PSP had battery problems, the iPhone had problems... Some products were struck with more problems than others, depending on which batch they came from. I guess you didn't get a good one."

---

"The Company is not aware of any reason for the recent share price volatility of its stock, as plans are moving forward as anticipated for the Gizmondo."

'Tiger Telematics press release', April 2005

I was lucky to get one at all. For all those parties and press releases, Gizmondo was mysteriously absent from actual shop shelves for most of its short life. According to Freer, this was down to a combination of financing and manufacturing problems. The Gizmondo was comprised of over 260 components, he says, many of which had long lead times. "The problem we had was the installed base. Going from zero to critical mass is a tall order. Without getting too much into the boring economics of everything, if we had gotten over the hump of scalability of manufacturing, we would have had a fighting chance."

Will claims the manufacturing issues were to down to poor planning rather than sluggish production speeds. "There was this thing about the NVIDIA deal for the graphics processor. They didn't even order enough silicone to fulfil those pre-orders," he says. "Looking back, if someone had done a bit of due diligence, it would have quickly become apparent that the kit wasn't there to do a significant launch of hundreds of thousands of units."

Freer admits that Tiger Telematics failed to deliver the full amount of pre-ordered units promised. He blames this on an inability to get financing as a new company. "I remember us struggling with that. It was hard to get any kind of bank behind us because there was little or no trading history for the product," he says.

"It was a somewhat odd corporate structure. We were a public company, but we were owned by a public company, and a lot of the financing was done through private equity fundraising efforts."

Louise puts it another way: "It was all smoke and mirrors, really. They didn't actually own anything. Everything was done with a strange partnership deal and the offer of shares."

She and Will both accepted shares for their services. The stock was restricted, which meant the shares couldn't be traded for two years, and only then if the company accounts were up to date. "There was no way that was going to happen, because the spending was just so awry," says Will. "I still have the shares today, but they're worthless. I might frame them."

---

"In 2004 and the first quarter of 2005, Gizmondo Europe paid Anneli Freer, the spouse of Mr Carl Freer, $116,000 and $57,831, respectively, for consultancy services. Mrs Freer provided marketing and public relations services, an introduction to the performer Sting and time spent in connection with the creation of the 'Agaju' gaming concept."

Tiger Telematics SEC filing, September 2005

While Tiger Telematics struggled to finance the manufacturing of its consoles, it had no problem paying its executives huge salaries and gigantic bonuses. Freer does not deny this, and nor does he make any excuses for it. He claims the salaries were below the industry benchmark.

"We had very talented people and we intended to keep them around, so we used every means we could to incentivise them," he says. "You get caught in a situation where the company suddenly fails and that incentivisation programme looks bad. That's a lesson learned, I guess. No one would raise an eyebrow at an executive running a company with $300 million profit getting paid a million bucks a year."

As chief technical officer, Steve Carroll was earning a million dollars a year plus share bonuses. His partner, corporate secretary Tamela Sainsbury, had a basic annual salary of $192,000. "What much of the popular press failed to mention is that myself, my partner and Messers Freer and Eriksson had not taken any salary for over two years in the start-up phase," Carroll says. "We all sacrificed our precious family lives and worked a minimum of 14 hours a day, including weekends. This was our self-perpetuated commitment but we knew that we had something special. Our shareholders knew exactly how hard we worked."

Then there were the cars. Will remembers visiting head office for the first time and spotting a Mercedes McLaren, a Rolls Royce Phantom, a Ferrari Enzo and a Maybach in the car park - "About 1.5 million quid's worth of car in total."

"A lot of that was exaggerated," says Freer, adding that some vehicles perceived to be company cars were actually owned by staff.

He is similarly unapologetic when it comes to the amount of money spent on developing and promoting the Gizmondo. "This is a big money business. Just to put things in perspective, we developed the Gizmondo at a third of the cost of what Nokia spent on the N-Gage. Start looking through the accounts of Sony and Nintendo, and you'll find the money we spent on development is chicken feed.

"You can't go in half-hearted. The plan was, obviously, that we were going to take this product and launch it on a worldwide platform. To do that, we had to spend what we needed to spend on the marketing side, to make ourselves heard."

Perhaps part of the problem was that Freer wasn't just looking at launching one product. A new, widescreen version of the Gizmondo was unveiled in September 2005, a month before the original model was due to go on sale in the US. According to Will, Freer had been touting it around since even before the UK launch: "It's the way he works. There wasn't really a chance to look at the detail, you were too busy struggling to keep up with the momentum this guy was creating."

Will says Freer would pull out a prototype of the widescreen Gizmondo at meetings that were supposed to be about the launch of the first machine. "You're thinking, 'Please put that away, you're not really helping the agenda for this morning. Can we get them to focus on this launch, the one you've mentally already done, as opposed to Gizmondo 2?'"

The official press photographs accompanying the widescreen announcement suggest the design was inspired by the Sony PSP, which had launched less than a year earlier. But Eurogamer has obtained images of a light grey version, brandished with the Xbox 360 name, symbol and even face buttons. So did Gizmondo have a deal in place to produce a Microsoft handheld?

"We were featured on the Windows CE Exhibition Tour for quite some time, even after the company went down," says Freer. "I think the mock-up was probably from one of the presentations with them, about how we could bridge the gap between the Xbox and the mobility. But no, there wasn't any agreement for us to do an Xbox device."

---

"Although Tiger's stock price has come under some pressure in reaction to Gizmondo receiving adverse media regarding some of its former employees' hitherto unknown past history that recently came to light, the company is far better positioned today than it was three weeks ago."

Gizmondo press release, October 2005

The widescreen Gizmondo never made it to market in any form. In October 2005, Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet published an article detailing the criminal history of Gizmondo executive Stefan Eriksson. More than a decade previously, he had been convicted of receiving stolen goods and attempted fraud. He was also said to be the leader of the 'Uppsala Mafia', a group allegedly responsible for committing violent crimes.

The article went on to reveal that Eriksson and Freer were co-owners of development studio Northern Lights. It was paid $3.5 million by Gizmondo to produce Chicane and Colours, two games that were officially developed by Indie Studios and Warthog. As other media picked up on the article, shockwaves began to reverberate through the games industry.

"That was when the long lenses started appearing in the hedgerow outside the Farnborough office," says Will. "Everyone had to leave early when the news broke, to get out of the way of the papers. Basically, it just turned into a massive clusterf***."

Both Freer and Eriksson resigned from Gizmondo. "The company was so far advanced, we were at a very mature stage of development and launch, and I thought the company could run without me," says Freer. "I hoped that by stepping away, it would just sort of go away. But it didn't. I regret not staying on board, to be honest with you."

For most of our interview Freer sounds relaxed, cheerful and philosophical about the way the Gizmondo saga ended up. But when the subject of the Aftonbladet article comes up, his tone changes. "Sweden suffers from the biggest epidemic in the world. It's called jealousy. Unfortunately, that article was fabricated from an agenda," he says.

"I'm talking about the power of share manipulators who have influence over what the media writes. When a lot of money is at stake, you start attracting people who are not interested in the longevity of the company but the performance of the stock. That's the dark side of running a company."

As I try to dig deeper and find out what he means by this, Freer accuses me of sounding "worse than a Swedish journalist". I point out that the Aftonbladet article and the revelations contained within it are part of the Gizmondo story, like it or not. But he won't be drawn on the details or identify who he thinks was manipulating the media. He simply states: "It's a story, I can tell you that. I'm saving it for my book."

By now Freer is chuckling again and his relaxed tone has returned. But I feel like maybe I've just had a taste of the famous temper I've heard mentioned before.

"You'd be fired at the end of one day because you said something out of turn, then you'd be hired again at 5am the following morning and told to go to Deutsche Bank with a suit on," says Will. He remembers one meeting in particular where he and others were trying to convince Freer there was not enough stock to launch the Gizmondo at Christmas, as was then planned.

"What he unleashed on me in that meeting... It was an experience I never want to repeat. He was the scariest guy alive to be on the wrong side of. Shouting, swearing, singling out, firing, rehiring, firing again...

"At that point I was willing to get on a plane to China and start making them myself. Just to make the bollocking stop. Even if there wasn't enough silicone, I didn't care. I would have gone out and gotten some sand and hit it with a hammer as many times as it took to make chips."

When Freer's rant finally ended, says Will, the atmosphere was terrifyingly still. "I've never been in a quieter room in my life. I'm sure after Hurricane Katrina, the people who survived stood up and went, 'It's really quiet here, isn't it?' It was similar, just in a more enclosed space."

Steve Carroll also recalls Freer being full of passion, but it doesn't sound as if he experienced it in quite the same way. "The atmosphere was always electric and Freer's enthusiasm was infectious," he recalls.

"Our brainstorming sessions used to scare new employees at first - shouting, swearing, laughing... But unlike the traditional brainstorming paradigms, 'no idea is a bad idea', ours were different. If you had a bad idea, you were told so."

"Gosh," says Freer, when I put the Katrina comparison to him. "I'm very passionate, so maybe that was a true statement. I think I got better with age. Maybe time fixes that. I don't think I'm described as Hurricane Katrina in meetings any more."

---

"Perhaps not since O.J. Simpson's low-speed freeway chase has a vehicle crashed so hard into the imagination of Los Angeles."

'We Can't Help But Gawk at the Ferrari Wreck', LA Times, May 2006

As it turned out, Freer's resignation did not keep Gizmondo out of the headlines. News of Stefan Eriksson's car crash, in February 2006, even made it into the mainstream media. This was partly down to the endless twists and turns - the Royal Bank of Scotland claiming ownership of the car, the gun clip found at the scene, the mysterious men in uniform who turned up claiming to be from "Homeland Security"... What did Freer think when he heard all that?

"I thought, 'What a great story for a video game,'" he says. "Obviously, it was disheartening. My first thought was hoping he was physically OK. But yeah, it was quite a shocker."

Much mention was made of Eriksson's previous convictions. Freer says he was aware of these long beforehand, adding that they have been overplayed in the media. "I don't think Sweden has a mafia. That terminology has been somewhat over-used. I knew about his criminal past, but when he started working for us he was not a wanted man. He'd served his time and paid his dues.

"He was very engaged, determined and he worked hard. I believe in rehabilitation, so that's one of the reasons we started working together. People deserve a second chance in life - sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn't."

Following the Ferrari crash, Eriksson was charged with grand theft auto. A mistrial occurred but he pled guilty to separate charges of embezzlement and gun possession and went to prison for two years. In 2008, he was deported back to his native country. In 2009, he was charged by Swedish prosecutors on seven counts, including attempted extortion and aggravated assault.

Freer is no longer in contact with Eriksson. "He's had some recent legal problems and I wish him all the best," he says. "I hope his luck turns round."

As the dust kicked up by the Ferrari's spinning wheels began to settle, the games industry was left scratching its head and wondering what just happened. The received wisdom seemed to be that the entire Gizmondo episode had been a scam. Freer disputes this, stating: "It's a slap in the face to anyone who spent time working on it to hear comments like that. Unfortunately some of the more colourful stories, particularly about Stefan and what happened in Malibu, were true. That's fuelled the scandalous element. For those of us who put a lot of time into it, it's a sad ending."

Former consultant Louise doesn't agree with the conspiracy theories either. "I don't think anyone sat around and said, 'We're going to do this massive scam,'" she says. "In their hearts, they were going to do this. Then they got in a bit deep financially and hit a few problems. You get to a point where you're in so deep you have to tell a few more lies, and I think that's what happened."

---

"I think the big change is the 'open-source' environment we will be offering, as well as some serious improvements on the component reliability side. No company Ferraris!"

Carl Freer, 'Gizmondo's Return', MCV, September 2008

The negative press surrounding Eriksson's car crash did nothing to dampen Freer's enthusiasm for the Gizmondo. In September 2008, he announced that the machine's successor would be launching in time for Christmas. But then, in December, he said the release had been delayed until 2009. "It's due to the economic climate in the US, as well as in the rest of the world," he told blog The Nordic Link. "It has affected us in our ability to fund and get funded in regards to the manufacturing of components." It seemed as though the new Gizmondo was facing the same problems as the old one.

Freer won't comment on what happened to the plans for the launch of Gizmondo 2 ("I have a current legal negotiation right now with regards to the ownership of the IP"). But when asked if he'd still like to resurrect the machine, he replies, "Are you kidding me? Of course." To successfully bring a product back to market after it failed the first time round is "any entrepreneur's dream", he says. But there is work to be done.

"The old version of the Gizmondo would never have a place in the market, but a new, improved and updated version... That's what we've been noodling on. How you could provide something that had more of an open app environment."

Steve Carroll has also kept the faith, both in the product and his former boss. "[Freer] could see through the windows of the future while the rest of us were guessing," he says. "Our firm belief is that version two would have rocked the world. Some of the things we were doing then, many can't do now, even with 60 per cent more processing power. We created a device which was ahead of its time. Given the chance again... There is still space for a third major gaming entity. You never know; never did like unfinished business."

Even Will and Louise say they'd do it all again.

"It was an amazing job. There was this ridiculous thing with this ridiculous name, and it was up there being mentioned in the same sentence as Sony and Nintendo," says Louise.

"The games industry has never been more interesting. It was so fantastical, no one could quite believe it was happening," adds Will. So what lesson did he learn from the whole experience?

"Listen to your instincts, and as long as the money's all right, ignore them," he says. "I would do the same thing again. It was a real rollercoaster ride; I've never had so much stress and fun combined. It was fantastic to be a part of it and I don't regret it for a second. It's just a shame it literally had a car crash ending."

Looking back, Freer says he would do things differently: "Errors were made, otherwise the company wouldn't have failed. As an entrepreneur, I've learned more from my mistakes than from any success I've ever had."

He's philosophical when it comes to the more scandalous aspects of the Gizmondo story. "Turn the page, move on. You have to let things lie. But there's always a part of you that hopes and dreams." In other words, it sounds as though Freer believes there's still a chance Gizmondo could make a comeback. "We did put some serious consideration into it a few years back, so who knows?"

---

"A weak race, and Gizmondo gets the most tentative of nominations."

'Yarmouth Bets', Sandracer.com, June 2007

Whatever the future might hold for Gizmondo the console, there's probably not much excitement in store for Gizmondo the racehorse. He was sold off by the liquidators in 2006. Records show he ran his last race in March 2010, coming seventh out of seven runners. Over the course of his five-year career he took part in 26 races, winning one. Still, with losses of £189 million on the table, he probably turned a bigger profit for his owners than his namesake.

"It would be a sad statement if that was the case," says Freer.

"But the company failed. So yeah, maybe the horse did make more money." Of all of it, that's the easiest thing to believe.